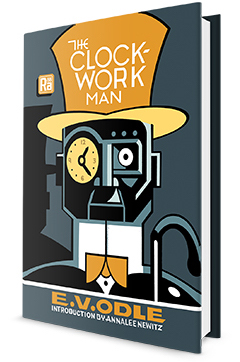

The Clockwork Man

by E.V. Odle, introduction by Annalee Newitz

The Clockwork Man--originally published in 1923--is a sometimes comic, sometimes disturbing feat of imagination, with a passionate sociopolitical message. It has now been republished as part of MIT's Radium Age series, an ambitious project seeking to bring attention to forgotten "proto-science fiction" from the underappreciated era between 1900 and 1935. In editor Joshua Glenn's series foreword, he makes the case that the Radium Age's achievements have been unfairly overlooked in favor of the so-called "Golden Age" of science fiction, an era beginning in the 1930s that established the towering influence of writers like Isaac Asimov. By republishing the little-known British author E.V. Odle's The Clockwork Man, among other neglected classics, Glenn and the MIT Press have made an excellent start at showcasing the strange wonders offered by the Radium Age.

Odle's novel uses the titular Clockwork man as a catalyst, a strange and unexpected interruption of sedate English life that begins when the malfunctioning creation wanders into a cricket match. The Clockwork man's herky-jerky movements and impossible-to-ignore wig make him a comic figure, and Odle mines humor from his bizarre interactions with the unfailingly polite cricketeers. He proves an amusing spectacle: "his actions produced an instantaneous appeal to the comic instinct; and in laughing at him people forgot to take him seriously." Here, Odle introduces an important theme of the book, which suggests that the radically new might appear absurd to onlookers who don't know any better, and that characters like the conservative-minded Doctor Allingham are inclined to use humor to laugh away anything that might disrupt their staid worldview.

A series of comic adventures follow, the Clockwork man's increasingly inexplicable and seemingly supernatural actions gradually forcing Doctor Allingham to abandon his detached disbelief for growing horror. Underneath the Clockwork man's wig, we learn, complicated clock-like machinery is attached to his skull, complete with a set of knobs that allow him to be tweaked and adjusted. He is therefore part man and part machine, and, according to Annalee Newitz, who writes the thought-provoking introduction, the first appearance of a true cyborg in literature. Further adding to his alien nature, is the Clockwork man's claim to have existed apart from time, in a kind of virtual, multiversal space that gives him immediate access to everything he wants and needs, in exchange for control over his emotions. As Newitz points out, Odle's conception of machine-amplified intelligence existing in a virtual space is suggestive of modern futurist and science fictional ideas about the Singularity, the theoretical merging of minds with computers that some believe promises to transform our world. To encounter the precursors of these futuristic ideas in an almost century-old novel is fascinating and exciting.

Revelations about the Clockwork man's inner workings take place alongside twin courtships: Doctor Allingham with Lilian, and the younger, more idealistic Arthur Withers with Rose. The Clockwork Man proves just as far-thinking about relationships between men and women as between man and machine. Odle engages the pressing, politically charged topic of gender equality head-on, as Doctor Allingham manages to alienate Lilian with his old-fashioned attitudes at the same time that Arthur's more egalitarian romance with Rose progresses. The issue of gender is woven into the science fictional element of the story as well, with the Clockwork man eventually revealing that, in the future, only the men have been shut away in clockwork universes that amount to gilded cages. In one of the novel's more bizarre revelations, we learn that some manner of beings descended to Earth and, together with women, mechanized all of the men after they were unable or unwilling to stop their ceaseless wars and exploitation. The Clockwork Man was published at a time when long-simmering grievances were boiling to the surface, and Odle's book argues that if the male ruling classes aren't willing to put up with change, they might find themselves shunted aside.

For all of its very serious concerns, The Clockwork Man is largely a comic novel, where even its dystopian elements are presented in absurd forms. The Clockwork man's constant malfunctioning leads to pratfalls and physical comedy reminiscent of a cyborg Mr. Bean, and the way he rudely interrupts the familiar workings of daily life creates ample opportunities for poking fun at familiar figures like the constable, who responds to one of the Clockwork man's rants about the fixed, finite nature of the world he's fallen into by saying "If you're going to drag algebra into the discussion I shall 'ave to cry off. I never got beyond decimals."

The Clockwork Man is an excellent example of the promise of the Radium Age series, giving deserved attention to a hilarious and prescient work of science fiction that has almost been forgotten. Those interested in the preoccupations of science fiction will be amazed to see some of its most familiar and compelling tropes introduced in a book well before the advent of modern computers, while others will find a tremendously entertaining novel with a witty, absurdist bent. At the heart of The Clockwork Man is a warning about what might happen in the absence of true equality and justice--that resonates a century later. --Hank Stephenson