|

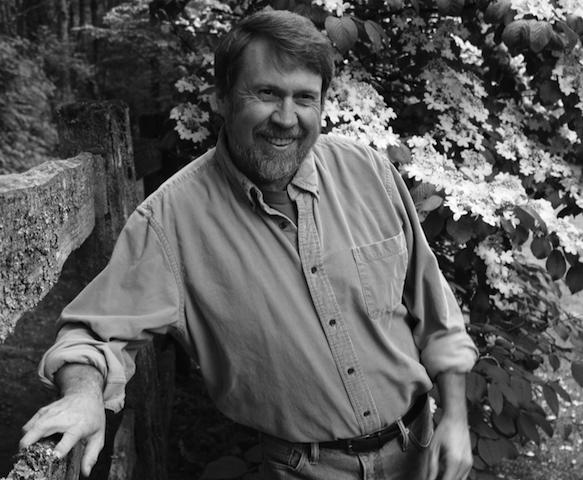

| photo: Robin V. Brown |

Raised and educated in California, Daniel James Brown taught writing at San Jose State University and Stanford before becoming a technical writer and editor. Under a Flaming Sky: The Great Hinckley Firestorm of 1894 (2006), his first book after turning his talents to writing full time, was named one of the best books of 2006 by the American Library Association and was a finalist in the Washington State Book Awards for 2007. The Indifferent Stars Above: The Harrowing Saga of a Donner Party Bride (2009) continued Brown's concentration on nonfiction narratives of significant historical events rendered compelling by in-depth portraits of the individuals involved and affected. Now, he has written an enthralling story of the 1936 Olympics rowing team from Seattle, The Boys in the Boat. Brown lives in the country outside of Seattle, Wash., with his wife, two daughters and an assortment of cats, dogs, chickens and honeybees.

You mention the serendipitous discovery that Joe Rantz, one of the rowers on the 1936 U.S. Olympic eight-man rowing team, was living next door to you. When did you realize that you had stumbled on a great story, one that could become a major book?

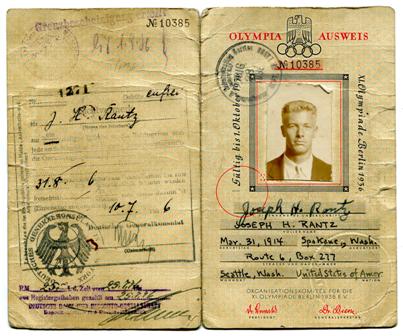

|

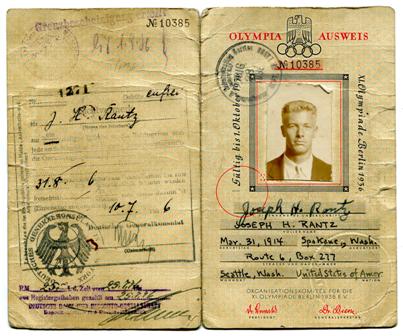

| courtesy Judith Willman |

The first time I talked with Joe about his upbringing and his crew experiences, I noted that tears came readily to his eyes at certain junctures. Men don't generally cry easily, so I knew immediately that there was something extraordinary going on. As he unfolded more of his story to me, I began to see that all the elements of a great tale were there—intense competition between individuals, bitter rivalries between schools, a boy left alone in the world, a fiercely demanding coach, a wise mentor, a love interest, even an evil stepmother. But I think what really clinched it for me was that the climax to the story was played out on an enormously dramatic stage—the 1936 Olympics in Berlin—and played out in the presence of Hitler and his entourage. Really, what more could a storyteller ask for?

What was your exposure to competitive collegiate rowing before you began this project?

I had virtually no experience with or understanding of collegiate rowing when I began my research. The only awareness I had of the sport growing up was that in the 1930s my father had been a huge fan of Ky Ebright's crew at the University of California, Berkeley. Ironically, Ebright turns out to be one of the principal antagonists for Joe and the boys in the boat, as Cal was their main rival through much of their story.

|

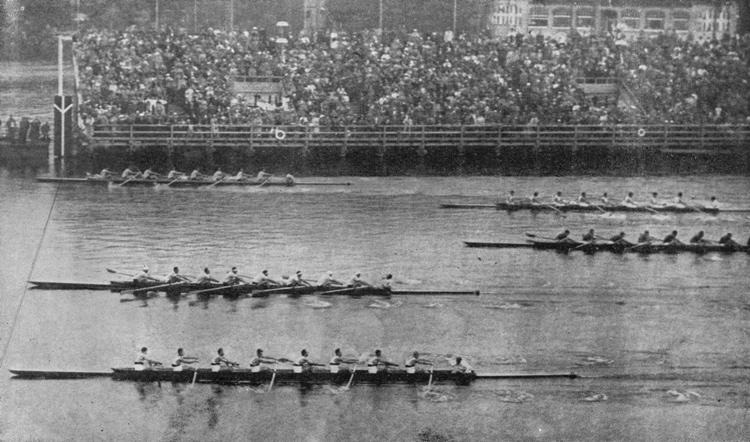

| Unloading in Hamburg. (photo courtesy Judith Willman) |

Because of my unfamiliarity with the sport, I strove to make sure I got everything right on a technical level as well as on a psychological level. I immersed myself in rowing lore, interviewed oarsmen and coaches, went out on the water with the freshman crew from the University of Washington, and generally learned everything I could about the sport. I don't think I've ever researched anything so thoroughly in my life.

Did you realize from the outset the variety of rivalries you would be uncovering in your research?

I understood the basic rivalries between the crews from different schools right from the get-go, but I discovered many of the deeper conflicts and rivalries one at a time as I did the research. And there were plenty to discover. The rivalry between West Coast and East Coast crews was really just one facet of a deep cultural and economic divide between East Coast and West Coast that predominated in many areas of life in the 1930s. In particular, the economic disparity between the homespun boys from the west and the very elite young men who rowed for many of the eastern schools couldn't have been starker, particularly at the height of the Depression. There was another real divide at work in the country with regard to how to deal with the rise of Nazism in Germany. Many wanted to ignore it; some wanted to confront it; a few even wanted to embrace it. We forget today how bitter the conflict over the proposed boycott of the 1936 Olympics was, and how systematically Jewish Americans were still excluded from much of American society.

All of the boys in the University of Washington boat were deeply affected by the economic catastrophes of the Great Depression, yet they continued their commitment to rowing. What kept their focus on the boat and the goals their coaches set for them despite the economic hardships they faced?

In some ways I think the hardships helped them focus and become what they were—arguably the greatest collegiate crew of all time. The ravages of the Depression humbled them, as it humbled everyone from bankers to janitors. But that humbling—the humility earned at the hands of hardship—was the very thing that allowed them to reach out to each other, come together, strive together for something that would transcend the hard times and redeem their lives. It allowed them, even compelled them, to throw everything they had into what they were doing on the crew, if not for their own sakes then for the sakes of the other fellows. I think that's what Joe's tears were about all those years later—the enormous gratitude he felt toward his crewmates for having joined with him in accomplishing the great feat of his life.

You bring the central role of Bobby Moch, the coxswain for the UW crew, to life in a thrilling way. How did you reconstruct his strategies for the decisive races you describe?

Bobby Moch passed away before I began writing the book, but I spent a good deal of time with his daughter, Marilynn, and in many ways she turned out to be a good proxy for Bob—smart, pugnacious, eager to talk. She also shared her father's scrapbook with me, and that was the source of many of the details of how he approached the races. When you hear some interviews Moch did later in life in which he talked very specifically about how he approached particular races, you really get an appreciation for how crafty he was. He thought through every race in advance but he was very quick-witted and particularly adept at improvising as circumstances changed. One of his favorite improvisations was to shout insults at his competition to take their heads out of the race. Another was to lie to his own crew about where they stood in the race in order to get a little more effort out of them.

You begin each chapter with a quote from George Yeoman Pocock, the man who built the rowing shells the boys in the boat used and a philosopher of rowing besides. How did you select those quotes?

Many of them come from Gordon Newell's excellent biography of Pocock, Ready All! Others are from his son Stan's equally interesting book, Way Enough! Still others I tracked down in various obscure publications. One even comes from an encouraging note Pocock wrapped around an oar before shipping it off to a U.S. Olympic crew. Since pretty much everything the man said was worth pondering, my job was just a matter of coupling quotes with chapters in ways that resonated with what I was doing.

How did Pocock's innovation in using western red cedar and its importance to rowing faster come to your attention?

The Husky Clipper, the cedar shell in which the boys rowed to Olympic glory in 1936, is on display these days in the University of Washington shell house, and all you have to do is take a quick look at it to appreciate what an extraordinarily beautiful thing a well-wrought cedar boat is. I think that's what first got me interested in the boat itself—just seeing it hanging from the rafters gleaming under the spotlights that are trained on it. But it quickly became apparent to me as I talked to Joe that Pocock and his craftsmanship and the wood he used were all mingled together at the heart of the story. It was from Pocock and his absolute devotion to his craft and the materials he used that Joe and the other boys learned to reach for a higher standard in all that they did, to revere something larger, and more abstract, than themselves.

The extent to which Adolf Hitler and the Nazis tried to use Berlin as an international propaganda tool for the 1936 Olympics is shocking not only in its attention to the minutest detail but also in its effectiveness. Did you find resistance to your digging into what was had been done in Berlin and Germany and how various parties turned a blind eye to what was going on?

The extent to which Adolf Hitler and the Nazis tried to use Berlin as an international propaganda tool for the 1936 Olympics is shocking not only in its attention to the minutest detail but also in its effectiveness. Did you find resistance to your digging into what was had been done in Berlin and Germany and how various parties turned a blind eye to what was going on?

This was absolutely the biggest revelation I experienced in doing my research for the book. I mean, I knew that the 1936 Olympics were a propaganda coup for the Nazi regime, but it really wasn't until I dug into the material that I understood just how deliberately, and cynically, the whole thing was choreographed. It also came as some surprise to me to realize how many Americans and Europeans attending the Games came away utterly snookered by the show. Even some of the boys came home feeling that Germany wasn't as bad a place as some were saying. All that quickly changed as the war threat deepened, but initially the scope of the deception and its success were both staggering. One of the most chilling things I came across was a Nazi propaganda book written and published in English by an American citizen. It read as if Goebbels himself had written it.

We know when we start reading The Boys in the Boat that this Husky crew will win gold at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Yet you produce one surprise after another and build nail-biting suspense into each race you describe. Do you have any tips for other writers for peppering narratives with thrilling surprises?

Ha! I have to admit that I was perplexed at first as to how I was going to make so many crew races interesting. But I soon found that each race really had its own rhythm, its own set of constraints, its own inherent drama. That said, I think one thing that helped was slowing time down and looking at each moment of any given race from every possible vantage point—what was happening in the boat, what was happening on shore, what was happening in the coaches' launches, what was happening in the heads of individual rowers. And it helps in re-creating the essence of the race for the reader, that any kind of race naturally builds to a crescendo of some kind, even if the crescendo comes before the finish. Other than that, I would just remind writers that you don't have to use something just because you happen to know it. The surest way to make something tighter and more compelling is to cut, not to add.

|

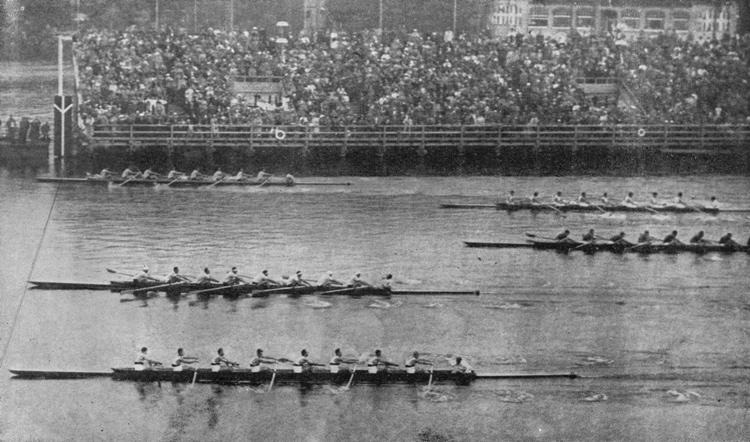

| Univ. of Washington Libraries Special Collections UW1705 |

In the final analysis, what do you find that a successful rowing crew requires?

Guts. After talking to many coaches and rowers one thing has become crystal clear to me: rowing is an extraordinarily demanding sport on both a physical and psychological level. People who succeed at it, at least at its highest level, seem to possess two seemingly irreconcilable traits: on one hand, a strong belief in themselves as individuals; on the other hand, a willingness to throw their egos overboard and subsume their individual needs and desires to the needs of the crew. It's a kind of paradox, and rowing coaches will tell you that it's terribly hard to find the right combination of self-confidence and selflessness. They will also tell you that putting together a whole crew requires a careful balancing act, mixing and matching personalities in such a way that they complement one another.

In the case of this particular University of Washington eight-oared crew, they bonded with one another in a way that lasted until the day they died. I see them as a kind of metaphor for that whole generation of men—the ones who lived through the Depression and the war and emerged as our fathers and uncles and grandfathers. I think they learned humility from what they endured, and humility became the gateway through which they were able to approach one another, extend helping hands to one another, and get things done. --John McFarland

The extent to which Adolf Hitler and the Nazis tried to use Berlin as an international propaganda tool for the 1936 Olympics is shocking not only in its attention to the minutest detail but also in its effectiveness. Did you find resistance to your digging into what was had been done in Berlin and Germany and how various parties turned a blind eye to what was going on?

The extent to which Adolf Hitler and the Nazis tried to use Berlin as an international propaganda tool for the 1936 Olympics is shocking not only in its attention to the minutest detail but also in its effectiveness. Did you find resistance to your digging into what was had been done in Berlin and Germany and how various parties turned a blind eye to what was going on?