Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital

by Sheri Fink

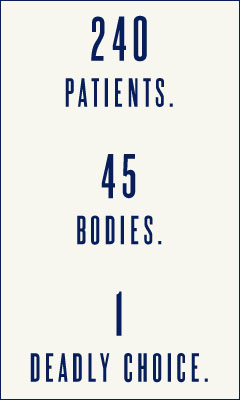

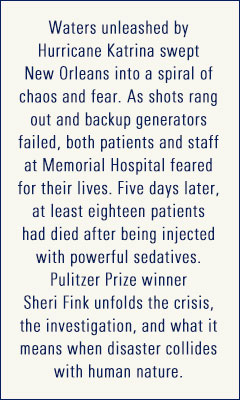

It has been almost eight years since Hurricane Katrina bore down on New Orleans, devastating the city and forever altering innumerable lives. In that time, countless stories of the individual tragedies, epic governmental failures, and rippling aftereffects that marked this disaster have been explored across all media--television, film, and hundreds of books. Despite all this coverage, however, new details of the hurricane and its aftermath continue to emerge. In Five Days at Memorial, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and physician Sheri Fink presents a meticulously researched examination of one of the most shocking stories to come out of Hurricane Katrina—the bodies of 45 patients found at New Orleans' Memorial Medical Center in the days following the storm; more deaths than at at any other comparable New Orleans hospital. An investigation into those deaths began almost immediately, and one year after the storm, a physician, Anna Pou, and two nurses were arrested and accused of euthanizing several of those patients.

There is no aspect of what happened at Memorial in the days following the storm that can be easily explained. It is a story of such complexity and so many moving parts that even the basic facts require careful examination. It is a credit to Fink's six years of research, which included numerous interviews, that she manages to re-create the increasingly chaotic scene on such a granular level that readers will have a visceral sense of what it might have been like to be there. Especially relevant to the story is the background information Fink provides. Opened as Southern Baptist Hospital in 1926, Memorial had been purchased in 1995 by Tenet Healthcare, a corporation based in Dallas. Like most hospitals in New Orleans, part of Memorial's back-up generator system was located at ground level, making it prone to flooding. Though recommended after Hurricane Ivan, retrofitting the hospital would have been costly and didn't happen. Nor did the hospital have a cohesive, written plan in place that would have determined how patients would be triaged in the event of a disaster. The hospital's helipad was also old, decrepit and difficult to reach. During the evacuation, Memorial staff members were forced to push patients through a hole in a machine room wall, into a parking garage, and up two flights of stairs to get them staged for the helicopters. Finally, the seventh floor of Memorial was leased by LifeCare Hospitals for critically ill or injured patients needing round-the-clock care, essentially creating a "hospital within a hospital" that had its own staff and administrators.

When Katrina hit, there were 2,000 people at Memorial. Roughly 240 of those were patients (52 of whom were LifeCare patients), 600 were staff, and the rest were family members. Some people had brought their pets. Though Memorial weathered the storm and its generators kicked on when the power went out, when the flooding began 24 hours later, it--like so many others in New Orleans--was marooned. The generators failed, knocking out the respirators that many patients relied on. The temperatures rose and patients spiked fevers of up to 105 degrees. Toilets backed up and became unusable, filling the hospital with stench. Patients began dying. Memorial and LifeCare staffers, all of whom were exhausted and operating on very little sleep, frantically begged Tenet for help via e-mail before their computers quit. Tenet wished them luck and told them to wait for FEMA. Evacuations were erratic and slow. Memorial's tenuous helipad route and structure made rescue even more difficult. Doctors began euthanizing pets. Many critical care patients, including neonates, were successfully evacuated, but many remained, their situations becoming increasingly dire. Doctors--and Fink points out that this was not a decision by any one person--came up with a triage system: those who could walk would be evacuated first, next would be those who needed more assistance, and scheduled to be evacuated last were the sickest patients and those who had Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders. As the days dragged on and the conditions inside the hospital worsened, the doctors, Anna Pou among them, began discussing "comfort care" in the form of morphine and Versed (a powerful sedative) for the patients they feared would not be evacuated. Ultimately, 18 of the patients who died at Memorial were found to have been injected with one or both of those drugs shortly before death.

To say that Five Days at Memorial is an engrossing read is a vast understatement. Throughout this horrifying, fascinating book, Fink maintains the highest journalistic standard. Her reporting is detailed, nuanced and far-reaching, yet it is never biased--a striking accomplishment in a story with this kind of moral complexity. And while the material devoted to the sweltering, desperate days and nights inside Memorial is stunning, the latter part of the book, which Fink devotes to discussing the legal wrangling that followed, is equally compelling. She gives voice to all sides--the doctors, nurses, families and patients themselves--and leaves the conclusions and judgments, none of which can or ever will be easily reached, to the reader. This is a book not to be missed. It is, quite simply, required reading. --Debra Ginsberg

Memorial was told to turn away sick people after the hurricane. That turns our assumptions about health care, mutual responsibility and community on their head. At what point does a hospital ethically become not a hospital, or can it?

Memorial was told to turn away sick people after the hurricane. That turns our assumptions about health care, mutual responsibility and community on their head. At what point does a hospital ethically become not a hospital, or can it?