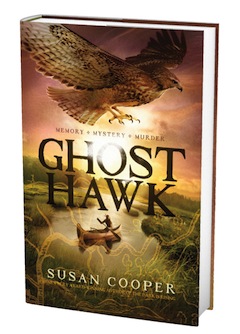

Ghost Hawk

by Susan Cooper

Ghost Hawk begins with the beauty of a place--its life-giving, life-sustaining beauty--with human beings as the stewards of its waters and shores, plants and animals. Little Hawk and his family have lived on and cared for this land for many generations.

Readers meet Little Hawk, of the Pokanoket Tribe of the Wampanoag Nation, when he is 11 winters old, as he prepares for his proving time. His mother and sister attempt to slip in some extra supplies, but his father intervenes. He gives his son a bow, a knife he got by trading his furs to a white man, and a tomahawk many years in the making. Its stone blade had belonged to Little Hawk's grandfather, and his father before him. Its handle had grown strong over the span of the boy's life as two strands of a bitternut hickory tree grew together, on an island in a saltmarsh. It was his father's work of art, with time as collaborator. "In my father's day, there was still time," says Little Hawk.

In prose that flows like poetry, Susan Cooper (The Dark Is Rising) establishes the sense of abundant time and land. Through Little Hawk's voice, she also conveys a sense of foreboding. Readers observe the rhythms of Little Hawk's daily life, his close relationship with his family, his peers and his village, as well as his closely attuned sense of his surroundings. Three other boys have come of age and will also begin their proving time, but each must accomplish his journey alone. As Little Hawk's father says, "He will come back a man."

After many tests, Little Hawk completes his quest--and returns to a village wiped out by plague. Only his grandmother, Suncatcher, remains. "The scar on your face says that you have come through danger," Suncatcher tells him. The destruction of his village is the first sign that the white settlers have made an irreversible change to their way of life. Little Hawk, Suncatcher and Leaping Turtle, who also returns safely from his proving time, join with another nearby village. The tribal leader, Yellow Feather, has chosen to offer help and friendship to the white settlers. But Yellow Feather suspects that it will not be enough; as an elder of the village explains, "I think our father Yellow Feather fears that they want the land."

Cooper portrays the range of attitudes toward the white settlers through Yellow Feather and his approach, his fellow villagers who are more skeptical of the settlers, and Squanto, who's aligned himself with the settlers. In a pivotal scene in the book, Squanto leads a group of the settlers into the Pokanoket village--the first white men that Little Hawk has ever seen. A white boy just five winters old is with them. Suncatcher offers the men and boy some of her freshly made fish soup, they--politely--refuse it ("The white man is not good at eating our food," Squanto explains). The unwitting rudeness makes a striking contrast to greeting-card images of pilgrims and Native Americans sitting down together at the first Thanksgiving. It's a hint at the kind of misunderstanding that builds into tragic consequences later in the novel.

The scene soon shifts to that of young John Wakely, the child visitor who was five winters old in the Pokanoket village that day. The narrative moves from the serene, elegiac tone of Little Hawk's narrative set in his village to the quickening pace and cacophony of sounds in the Puritan settlement. Through John's perspective, readers gain exposure to the strong views at opposite ends of the settlers' spectrum: those who believe the newcomers should honor the ways of the Native Americans, learn their language and live peacefully beside them, and others who perceive the differences between the two cultures as a chasm. They judge even their own, less rigorously religious countrymen harshly. They cannot imagine that the Pokanokets could have traditions or an ethical code as strong as their own. John, at age 10, nearly the same age as Little Hawk was when he entered his proving time, witnesses an event of such injustice that it shapes the man he will become.

At the heart of the conflict lies the settlers' conviction that one can own land outright, and the Native American belief that the land and all of its bounty belongs to the Great Spirit--no human could own it. Cooper skillfully structures a novel in which young readers come to see the misunderstanding take root, through the eyes of two sympathetic characters--Little Hawk, of the Wampanoag Nation, and John, who arrives with the white settlers. Few characters are all bad or all good. She allows us to see the complexities and motives--mainly a desperation to survive and to preserve the values they hold dear--on both sides. A timeline and author's note credit the primary sources and other documents Cooper used in her research.

This moving and thought-provoking novel invites young readers to consider the lasting legacy of the conflict between the first people who lived in this land we call America and the new arrivals who began to claim it for themselves. Little Hawk and John Wakely may be fictional characters, but they stand in for hundreds of real human beings, past and present, and their love of the land and their dream of peace. --Jennifer M. Brown

You say of your home that it's "not possible to live here without listening to the land." How did it first speak to you?

You say of your home that it's "not possible to live here without listening to the land." How did it first speak to you?  These early chapters demonstrate to readers how closely connected the Native Americans are to the land. You write, "Thousands more of the white men continued to arrive from over the sea, and their settlements multiplied and spread, as our father Yellow Feather and other sachems sold them the use of land. This selling was not what either side thought it should be." Is this the crux of the matter?

These early chapters demonstrate to readers how closely connected the Native Americans are to the land. You write, "Thousands more of the white men continued to arrive from over the sea, and their settlements multiplied and spread, as our father Yellow Feather and other sachems sold them the use of land. This selling was not what either side thought it should be." Is this the crux of the matter?