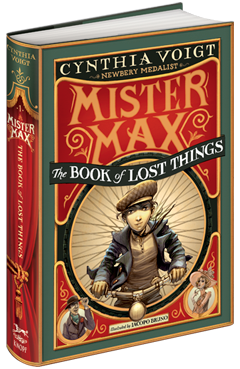

Mister Max: The Book of Lost Things

by Cynthia Voigt, illus. by Iacopo Bruno

Even when Max Starling's parents are home, they pay him little heed, so caught up are they in their theater and theatrics. No wonder Max has grown into the charmingly resourceful, independent and observant 12-year-old he is.

When his parents accept an invitation from the Maharajah of Kashmir to create a theater company for him, they plan to take Max with them. But when he arrives at the dock to meet them, and discovers they've boarded a ship that departed early--without him--readers believe he's a boy who can survive on his own (with a little help from Grammie). Max's chief concern is that the boat his parents supposedly boarded, the Flower of Kashmir, does not exist, according to the harbormaster. He's not sure where they're bound, nor can he make any sense of a cryptic note his parents left with a clerk. That's just one--albeit the largest--of the mysteries Max explores and attempts to solve in this first of a planned trilogy from Newbery Medalist and Edgar winner Cynthia Voigt (the Tillerman Cycle; The Callender Papers).

Like his parents, Max is a master of disguises--luckily, for he must hide the fact that his parents have gone missing so that he can stay put. Grammie, his maternal grandmother, lives next door and cooks him supper. But given her modest salary as a librarian, Max must find a way to support himself. He stumbles into a vocation when he discovers a toddler wandering in the park, and attempts to unite the boy with his mother--without asking a lot of questions of the people nearby. "He didn't want anyone noticing him, wondering about him, looking for explanations," Max thinks to himself. "He hadn't yet figured out what lies he could safely tell; he just knew what truths he had to keep hidden." Max finds the boy's mother, who is grateful to have found her boy, Angel, and handsomely rewards Max. He begins to think of himself as "Mister Max, returner of runaway children."

Like Dickens, Voigt gracefully employs a third-person narrative that allows her to move freely among her characters' perspectives. Her choice of setting--an era when people traveled by ship and communicated by letter--permits a formality of language and manner that suits young Mister Max. Word of mouth leads to the hero's next two jobs: finding a lost golden retriever (called Princess Jonquilletta of the Windy Isles) owned by a wealthy child named Clarissa, and a lost heirloom spoon belonging to the Baroness Barthold. In both cases, there is more than at first meets the eye. Clarissa believes a jealous classmate may have stolen the purebred. Max poses as a substitute teacher to find out more, which leads to a chance meeting with Pia, a friendless, intelligent girl, who confides that the pets tied up at the fence at school are "just a contest they have, to be the one with a pet everybody else wishes they had." This information poses a larger moral question for Mister Max: Should he return the dog to its owner?

Max's knowledge of theater overall and of Shakespeare in particular often leads to the solutions he seeks for the dilemmas he's hired to fix. As Max says, "You can't know a lot of plays well, some of them written by William Shakespeare, without getting a good understanding of how and why people do what they do." Voigt's twist is that Max often lands on a resolution that pleases him as much as his clients--which is why he comes up with the job title "Solutioneer."

With humor and wit, Voigt plays with the idea of what it means to be lost. Princess Jonquilletta of the Windy Isles is not lost; the dog ran away. So how can Max do right by the dog but also satisfy his client? And Max discovers there's a far greater loss for the Baroness than the family spoon: when she accused an employee of stealing it, the Baroness also came between her grand-nephew and the love of his life. He did not stand up for his beloved, and lost her--a loss more precious than any spoon. He then flees, and the Baroness loses him, too.

Voigt's supporting cast will captivate readers nearly as much as Max does. Grammie knows just when to step back and give Max room, but also when to step in and be the adult. She also finds Max a tutor, whom the boy recruits as a boarder, and who becomes another trusted confidant for Max. His art teacher, Joachim, comes across as crotchety, but also serves as a guiding force for Max. By book's end, the mystery of his parents' whereabouts is not fully concluded, but readers will be confident that Max--with the help of his chosen group of guardians--will be quite alright. --Jennifer M. Brown