Innocence

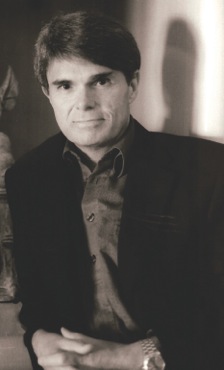

by Dean Koontz

Dean Koontz knows exactly what story you'll be thinking about after the opening chapters of Innocence. His narrator-protagonist Addison Goodheart, a shunned outcast who lives alone deep below the city streets, comes up to the surface late one night and, making his way through the public library, catches sight of a haunting young woman fleeing an angry pursuer. Once the threat has passed, Addison figures out where she must be hiding and reaches out to her; she agrees to meet and talk with him. "I have no illusions about romance," he tells her during that first conversation. "Beauty and the Beast is a nice fairy tale, but fairy tales are for books."

Of course, Innocence is a book, and so ultimately there will be much of the fairy tale in Addison's account of how he becomes 18-year-old Gwyneth's companion--not so much her hero or protector as a bearer of witness. Gwyenth's father was murdered by the man who had stolen much of his fortune, the same man from whom she was running earlier (who has an even more sinister fate in mind for her). Addison tags along as she tries to find evidence of this villain's crimes--and stays with her as she scrambles to protect those closest to her from the inevitable attempts at revenge. He has fallen in love with her, and his devotion is absolute. "She would always be blameless," he tells us, "for I knew the purity of her heart."

Their relationship, however, is heavily circumscribed. She forbids him even the most fleeting of physical contact, while he buries his face in a hooded sweatshirt and a scarf lest she catch a glimpse of his face. As we learn from the periodic flashbacks, there's something in Addison's appearance that so disgusts others that anyone who sees him is overcome by a murderous impulse. Even the midwife who assisted at his birth wanted to strangle him, and though his mother saved his life on that occasion, after eight years living with him in the woods, she pushed him out into the world beyond their cabin. He makes his way to the unnamed city, where he finds another outcast, whom he calls Father, "but back then we needed no names because we spoke to no one but each other." Father was killed eight years ago, and until his encounter with Gwyneth, Addison has been painfully alone.

Addison and Gwyneth's city has an ethereal quality to it, and not just because of the blanket of snow that covers its streets. The novel's highly detailed scenes feel tenuously connected to each other the way disparate elements coalesce in dreams and, at times, Koontz's choices about where to invest specificity initially seem odd: Why, for example, do we need to know so much about the dead woman found in a koi pond years before Addison and Gwyneth meet, or the extended conversation between two priests Addison once overheard hiding in a cathedral? When our "real" world intrudes upon the storyline, whether in fleeting references to China and North Korea in a snippet of television news or an allusion to the Catholic Church's sex abuse scandals or the comparison of a winter street scene to a Thomas Kinkade painting, the dream-like atmosphere may be momentarily interrupted, though Addison's narration always serves to swiftly restore the mood.

Everything in Innocence is connected to everything else, it turns out, in ways that prove surprising. By the time we learn the truth about Addison's condition, so many of our initial assumptions have been upended it may feel as if we've been given a completely different book--that what started out as a fairy tale has become something much more allegorical.

Because of those unexpected elements, Innocence may require some readers to keep an even more open mind than usual. As in any allegorical tale, realism can take a back seat--Gwyneth, for example, frequently sounds nothing like any real-life 18-year-old girl, but her dialogue, along with other plot elements that could be interpreted as baroque or melodramatic, serve specific symbolic purposes. (To put it another way: Innocence absolutely is a baroque melodrama, and it works.) If you can't figure out why Koontz brings something into the story--like the "Clears," translucent beings who periodically appear to Addison floating around the city, wearing "soft-soled white shoes, loose pants with elastic waists, and shirts with three-quarter sleeves... as if they were dressed to staff the emergency rooms and surgeries at various hospitals"--give it time. Eventually, the subtexts will all be revealed.

For readers who primarily know Dean Koontz as a purveyor of horror, however, the results may be unexpected. Longtime fans may see in Addison Goodheart a refined spiritual cousin to earlier Koontz heroes like Slim Mackenzie, Jim Ironheart or Odd Thomas--and one who bears an ultimately hopeful message, at that. As a modern-day fairy tale, Innocence proves, in its own way, as inspiring as William P. Young's The Shack or Mitch Albom's The Five People You Meet in Heaven. --Ron Hogan

"Readers have often asked me how many ideas I get from dreams,"

"Readers have often asked me how many ideas I get from dreams,"