_Frederic_Stucin_Pasco_Co.jpg) |

| photo: Frederic Stucin Pasco |

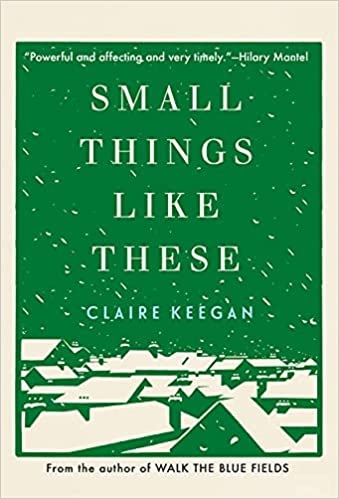

Claire Keegan is an Irish writer best known for her short stories. Her first collection, Antarctica (1999), won the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature. Her writing has appeared in Granta, the New Yorker, the Paris Review and elsewhere. Her novel Small Things Like These is available in the U.S. from Grove Press (reviewed below).

Small Things Like These is a story of a family but it intersects with the history of the Magdalene laundries. What initially drew you to write about this topic?

I'm not drawn to topics at all. I was never drawn to the topic. It's not how I write, or why I write, or how I begin. It's not a word I would ever use. I write about people and about life and how people cope and sometimes cannot cope and the decisions we make or the decisions we cannot make, and I just take the characters along through time. I depend on and have some faith in my own aesthetics with regards to prose, in that I believe if it's something I'm deeply interested in and wrap my imagination around that something will come out to meet me somewhere in the middle and that I'll have something to say.

What is the process of starting something like this for you?

Well, it's just a piece of difficulty. You're writing about something, and you don't know what it is. I didn't have Furlong at the beginning, I didn't have his past, his daughters, his wife, the shop, the river, the convent. I had nothing. So, I started with pretty much nothing. And as I say, it's just kind of an act of faith that this might turn into something that might be decent and have something to say. I just write one flat paragraph after another, slowly, until something emerges with some level of suggestion. And when I feel any suggestion in a paragraph, I know there's something there and it is something I'm able to detect. And then I just try and follow and stay with that and see where it leads me. I don't believe I have ever not wanted to be led wherever it takes me.

You don't reject the material. Whatever material, it is usually better than what you have in mind. I think prose likes to test you to see how patient you are and how serious you are and if you're serious about this. And if you're serious about it and want to do your best work--which is what I always want to do, I'm not saying it's what I always do, but it's what I always want to do--if you want to do your best work, it opens the door and says, "Well alright, let's see what you can do." I felt a door opening on Furlong and his family and a coal yard and a convent and a town in Ireland during a cold, wet winter. That isn't what I would have chosen for myself. But that's what I got.

Was there any particular theme that grounded the story for you?

If themes emerge--and I hope they do to the reader--I try to stay blind to them. I still couldn't tell you what the theme of this book is. It's not how I think about stories. I always became frozen when people asked me about themes in school because I took stories very seriously. I thought it was about a man going down the road with a goat and the goat went into the woman's house after stealing his cap and that meant he had to marry her and that was very serious to me. I still regard stories in that same way. But I suppose if you wanted me to nail down something, I'd probably say it's a story about love. About a man who was loved, even though he lost his mother when he was young. He was actually loved more than he knew. And I think it's something he wants to offer in his own life. Maybe the book is about how he does this and how he questions if he should do it at all.

Are there any books or authors that you've read recently that have blown you away?

Are there any books or authors that you've read recently that have blown you away?

I really liked Damon Galgut's book The Promise which just won the Booker Prize but then I have an interest in Damon's work because I've taught The Good Doctor and some of the stories and I liked In a Strange Room. I think he's a very light-handed writer, so I was delighted for him to have won the Booker this year. Usually, I read the dead. A joke amongst my students--I teach creative writing or have taught creative writing--is, "Such in such a writer is dead, Claire, you can read him now." They tease me because I'm inclined to read the Russians and Fitzgerald and Jane Austen and Joyce. I'm going to read Proust over Christmas. I'm afraid I'm the last person to ask about advice on what is new and upcoming and the state of literature as it is now in Ireland or elsewhere. I'm re-reading Dubliners at the moment and listening to all the stories again and again, just to see what he's doing there.

Small Things Like These is set around the holidays, which feels perfect but not pre-planned. Why did the holidays emerge as part of the setting for this piece?

That's what I like--I like things which work but don't seem pre-planned or plotted out in any way or devised and that's certainly how it started but it just felt like a winter book. Also, because Furlong's a coal and timber merchant it would keep him busy, it would give him some income, it would take him around to all those places. I suppose the whole season of Christmas is a time when the shield we ordinarily wear gets a bit thinner for some of us. And I think that's what happened to Furlong on Christmas Eve after he's fed his men. His shield gets a bit thinner and he's at a loose end.

There's a section in that chapter where he's making the Christmas cake and he wonders what would happen if they had time, if they had free time and if they would have better lives or if they would lose the run of themselves. It says, "Always it was the same, Furlong thought; always they carried mechanically on, without pause, to the next job at hand. What would life be like, he wondered, if they were given time to think and reflect over things? Might their lives be different or much the same--or would they just lose the run of themselves?" And I think actually when he pauses on Christmas Eve and finds himself at a loose end, he loses the run of himself. To me, it's the story of a man breaking down. To me, it's self-destruction in the guise of heroism. --Alice Martin, freelance writer and editor

Claire Keegan: Writing as an Act of Faith

In Hello Baby Animals, Who Are You? by Loes Botman (Floris Books, $9.95), children can identify different animals and are invited to learn the special name for each kind of baby. The illustrations, in a soft, nearly pastel palette, allow each baby animal the chance to look indescribably darling on its identifying page. "I'm a wobbly foal, says the baby donkey," legs spread in an unsteady posture; "I'm a playful kid, says the baby goat," its expression a near smile as it is captured mid-leap.

In Hello Baby Animals, Who Are You? by Loes Botman (Floris Books, $9.95), children can identify different animals and are invited to learn the special name for each kind of baby. The illustrations, in a soft, nearly pastel palette, allow each baby animal the chance to look indescribably darling on its identifying page. "I'm a wobbly foal, says the baby donkey," legs spread in an unsteady posture; "I'm a playful kid, says the baby goat," its expression a near smile as it is captured mid-leap. Anita Bijsterbosch places animals together in shared spaces in Animals at Play (Clavis, $14.95). All of Bijsterbosch's animals are brightly illustrated with a wide-eyed sweetness that is immediately endearing. On the left-hand page, the animals are depicted--Animals in the Jungle: parrot, elephant, giraffe, snake, lion--and on the right, a lift-the-flap shows the animals having fun together in the jungle. Other locations include the ocean, the woods, the farm and the garden.

Anita Bijsterbosch places animals together in shared spaces in Animals at Play (Clavis, $14.95). All of Bijsterbosch's animals are brightly illustrated with a wide-eyed sweetness that is immediately endearing. On the left-hand page, the animals are depicted--Animals in the Jungle: parrot, elephant, giraffe, snake, lion--and on the right, a lift-the-flap shows the animals having fun together in the jungle. Other locations include the ocean, the woods, the farm and the garden. Amelia Hepworth and Cani Chen's Hello, Baby Animals! (Tiger Tales, $6.99) is designed to help the youngest of children engage with books. Since babies can see black-and-white images from birth, this title features high-contrast black-and-white art with fluorescent splashes of color on every page. Chen sketches every animal with thick black or white lines, and the pops of color show up as waves around a turtle, snowflakes around a penguin or flowers around a deer. Hepworth's simple text puts each animal in action, such as "Kitten purrs" or "Puppy plays." --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Amelia Hepworth and Cani Chen's Hello, Baby Animals! (Tiger Tales, $6.99) is designed to help the youngest of children engage with books. Since babies can see black-and-white images from birth, this title features high-contrast black-and-white art with fluorescent splashes of color on every page. Chen sketches every animal with thick black or white lines, and the pops of color show up as waves around a turtle, snowflakes around a penguin or flowers around a deer. Hepworth's simple text puts each animal in action, such as "Kitten purrs" or "Puppy plays." --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

_Frederic_Stucin_Pasco_Co.jpg)

Are there any books or authors that you've read recently that have blown you away?

Are there any books or authors that you've read recently that have blown you away? American author Noah Gordon, "who was virtually unknown at home but whose novels about history, medicine and Jewish identity transformed him into a literary luminary abroad," died November 22 at age 95, the

American author Noah Gordon, "who was virtually unknown at home but whose novels about history, medicine and Jewish identity transformed him into a literary luminary abroad," died November 22 at age 95, the