Years ago, I was a book snob about romances. Trifles, I thought, not "real" writing. Then a friend challenged me to read one of her favorite romances. It was by Laura Kinsale, and I think it was about a man who was suffering from PTSD, but in the 18th century. I loved it, and started reading and recommending (with limited success) romances to people; even now, the genre is a tough sell to someone who thinks it equals trash. (For a good discussion about the popularity of romance novels, see Dangerous Men and Adventurous Women: Romance Writers on the Appeal of the Romance, edited by Jayne Ann Krentz, from the University of Pennsylvania Press).

Romances are hot news right now--we all know why--and controversial. We wanted to talk to a romance author about Fifty Shades and the current state of romance writing; Katharine Ashe (How to Be a Proper Lady, etc.) agreed to step into the fray.

Romances are hot news right now--we all know why--and controversial. We wanted to talk to a romance author about Fifty Shades and the current state of romance writing; Katharine Ashe (How to Be a Proper Lady, etc.) agreed to step into the fray.

How has the the romance community reacted to Fifty Shades?

The romance community's reaction to the popularity of Fifty Shades has been mixed. Some love the books (one writer friend of mine called them "crack-tastic") while others adamantly don't. Mostly, though, we've shaken our heads in wonder. Fifty Shades doesn't represent a revolution in women's fiction. The romance industry has been publishing erotic romance, including BDSM novels, for years. That said, we are a little excited. There's a hope that non-romance readers who've enjoyed Fifty Shades will now venture farther into the genre and discover how wonderfully rich and varied romance can be.

Why do you think it is so popular?

I've heard readers suggest that the simple, somewhat masculine cover and non-flowery title went a long way toward selling the book at first. According to this theory, since Fifty Shades is not packaged like a romance novel, the reader is less likely to feel shame for being seen reading it. Once the book became popular and recognizable, the stakes changed. It's not shameful to read a book that hundreds of thousands of other folks have read.

I've read many bloggers and reviewers trying to justify its popularity. The writer that most intrigued me suggested that the popularity of Fifty Shades has more to do with economics than sex. In a time of general financial uncertainty, the fantasy of being swept into the life of a billionairess straight from college by a handsome, powerful man in exchange for one sacrifice is far too appealing to resist, whatever that sacrifice may be.

One popular fantasy represented in many romance novels--though not all--is the emotionally untouchable alpha hero who finally succumbs to the love of the one woman able to make him explore and admit to his true feelings. He protects and provides for her; she nurtures and teaches him. In this scenario the hero is wealthy and powerful, and the heroine is often of a lesser economic or social status. It's the Pretty Woman syndrome. Fifty Shades takes that dominant-submissive dynamic quite literally into the sexual realm. But this relationship dynamic (aside from sex) is common enough in romance fiction that it's not remarkable. Again, though, this type of hero/heroine pairing is not ubiquitous in romance novels now. In most romances, the nurturing and teaching go both ways. Through their relationship, the heroine helps the hero change for the better and vice versa.

The impulse to defend even bad romance writing is understandable, since we still seem to be in a place where romance is not taken seriously. Within the romance community there is critical reviewing, but it seems when an "outsider" criticizes, the wagons circle.

Despite its vast success, the romance industry continues to take hard hits from "outsiders," and while thrillers and mysteries occasionally find their way into the New York Times Book Review, romance is mostly ignored by non-industry book reviewers. I've suggested elsewhere that to ignore or indeed denigrate a vastly successful industry that is controlled largely by women, and to unrelentingly criticize the product of that industry which is consumed largely by women--especially one that celebrates female sexuality--points to a latent misogyny in our culture. Most Americans don't like to hear that. But though we've made significant strides, we're still a long way from true equality of the sexes, and ancient (literally ancient) misconceptions and prejudices about female sexuality unfortunately linger.

When it comes to criticism from outsiders, romance writers do indeed often band together in defense of our genre. The romance industry is a sizable community, but for the most part our similarities are greater than our differences. This is a good thing! Few industries are so cohesive and mutually supportive despite internal diversity. For instance, I write mainstream hot historical romance, while my roommates at the RWA national conference every year, Isabelle Drake and Dana Corbit, are authors of, respectively, erotic romance (including ménage and BDSM) and Christian inspirational romance. Isabelle, Dana and I respect and care about each other because we share a love of writing, a dedication to our readers and a profound belief in Happily Ever After.

What are the elements of a "good" romance? Why is the outcome usually marriage (usually with children) or a stable relationship? What does this say about our need for archetypal stories?

RWA's definition of a romance novel includes "a central love story" and "an emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending." Despite the many other options in contemporary American society, marriage is still the normative conclusion to a successful love relationship--meaning it's still generally perceived as such, and the state generally supports that. Although romance readers represent a varied demographic, they expect a Happily Ever After and they know that usually includes a wedding or at least a marriage proposal.

Readers and writers alike, however, are divided on the subject of children. Some readers adore "Baby Epilogues" while others dislike them intensely.

Recently at a romance book club that I attend (as a reader), the group's opinion was unanimous on a related matter. If a heroine's career is important to her sense of self throughout the book, but she gives it up to become a wife and stay-at-home mom at the end of the story, that is entirely unacceptable. Romance readers are smart, most of them work hard in or outside the home, and they don't like it when an author plays fast and loose with characters.

We get at least one e-mail a day touting the next Fifty Shades. So what will happen to romances now? Will authors be asked to add more sex? Will they be marketed differently?

I don't think there's anything to worry about. Currently you can find nearly every sort of heroine imaginable on the pages of romance novels, from the most demure to the wildest. The genre is huge, including a vast array of contemporary and historical settings, from Christian inspirational to erotic romance, and into fantasy, sci-fi and the paranormal realms, too. Subgenres come (vampires are quite popular now), and subgenres go ("chick lit," for instance), but the industry is large enough and the readership is expansive enough to allow for great variety. Currently "mainstream" romance can be very sexy indeed. Is it all sex and no substance? Absolutely not. Wit and intelligence never go out of style, and a beautifully written book will always find an appreciative audience among romance readers. --Marilyn Dahl

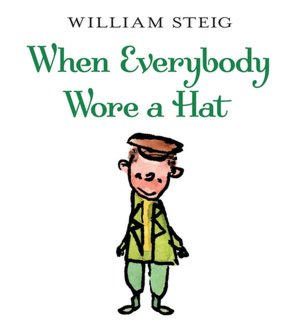

Chuck Close may be better known for his portrait paintings, but he's certainly articulate about his artistic process in Chuck Close: Face Book (Abrams, reviewed below). He makes a case for art as a lifeline. William Steig's When Everybody Wore a Hat (HarperCollins) serves as a series of connected captions for his humorous and poignant artwork. It's a lesson in the telling detail. Similarly, in I Can't Keep My Own Secrets: Six-Word Memoirs by Teens Famous & Obscure, edited by Larry Smith and Rachel Fershleiser (also Harper), half a dozen words speak volumes about a person, if they're the right ones.

Chuck Close may be better known for his portrait paintings, but he's certainly articulate about his artistic process in Chuck Close: Face Book (Abrams, reviewed below). He makes a case for art as a lifeline. William Steig's When Everybody Wore a Hat (HarperCollins) serves as a series of connected captions for his humorous and poignant artwork. It's a lesson in the telling detail. Similarly, in I Can't Keep My Own Secrets: Six-Word Memoirs by Teens Famous & Obscure, edited by Larry Smith and Rachel Fershleiser (also Harper), half a dozen words speak volumes about a person, if they're the right ones.

Rosanna Chiofalo

Rosanna Chiofalo Romances are hot news right now--we all know why--and controversial. We wanted to talk to a romance author about Fifty Shades and the current state of romance writing;

Romances are hot news right now--we all know why--and controversial. We wanted to talk to a romance author about Fifty Shades and the current state of romance writing;