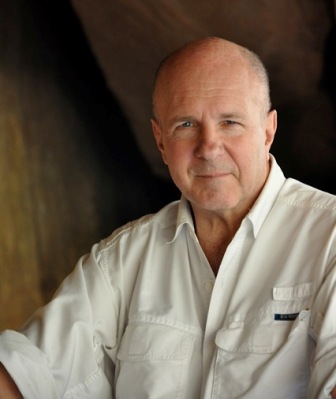

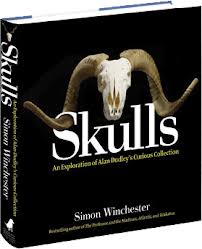

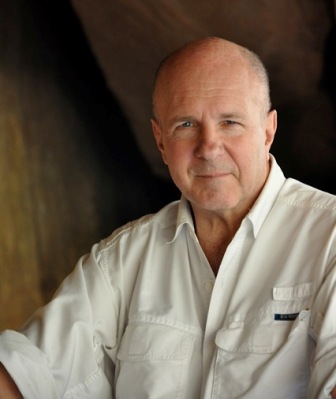

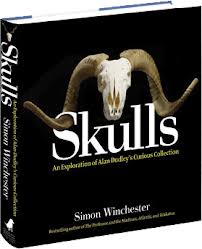

As a journalist, Simon Winchester covered everything from the Belfast Hour of Terror to the invasion of the Falkland Islands--even winding up in prison, suspected of being a spy. He then went on to write travel books and eventually narrative nonfiction, starting with The Professor and the Madman, which told the story of the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary. Winchester's new book is a coffee-table volume called Skulls: An Exploration of Alan Dudley's Curious Collection (Black Dog & Leventhal) that highlights craniums from the vast array of Earth's animal species.

Skulls is a very different book, both in terms of content and structure, for you. How did you choose this "curious collection" as your topic?

Skulls came about in a rather peculiar way. Two years ago, friends of mine in London alerted me to a curious story in the Daily Mail about a man who had been arrested, found with "animal parts" in the bedroom of his very ordinary suburban house in the English midlands. We were curious about the finer details of the story--and knowing that the Daily Mail, a tabloid newspaper, is notorious for writing cleverly rousing articles that often (to put it kindly) shade the truth, decided to look into it more carefully. As we suspected, we found that instead of some kind of Hannibal Lecter depicted in the article, Alan Dudley was a mild-mannered collector with a wide knowledge of chordate biology, who had spent a lifetime assembling one of the finest collections of animal skulls known. He had, to be fair to the police, made a small number of unwise purchases of the skulls of creatures for which trade is banned under CITES [Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species]--but we accepted that he had bought these skulls (of such animals as a loggerhead turtle, a penguin and a Goeldi's marmoset) in good faith, and had no intention to breach any of the rules that prohibit trading in endangered species. That being so, we decided that his collection was so remarkable--and his own personal story so intriguing--that it would make an excellent topic to pursue.

What kind of reactions did you get when you pitched the book?

Generally the reaction of publishers followed a linear and swiftly moving trajectory--beginning with an immediate reaction that was an amalgam of incredulity and shock, to a rapid realization that in fact the collection was of such quality as to illustrate something that was both fascinating and important. What then solidified the publishers' enthusiasm was our decision not to limit ourselves (and by "ourselves" I mean the photographer Nick Mann and I) just to the material in his collection, magnificent though this was. We wanted also to use the collection as a peg on which to hang a detailed meditation on the role of the skull generally in human culture--a subject which, though seldom written about except in scholarly journals, is in fact immensely captivating. So I was able to write about the skull as a symbol of power (in the Nazi army, on pirate flags, with the Hell's Angels), the skull even as a figure for celebration of the inevitable, as it remains to this day in Mexico.

I think this is why I was so personally fascinated in writing the book: the topic extended far beyond the taxonomic complexity and completeness of the collection itself--which would have made a wonderful book on its own, I am certain--and wandered into so many other realms of human behavior and history. Of all the books I have written, this was perhaps the one that surprised me most: what began as a fairly small and circumscribed study of just a collection, albeit a remarkable one, evolved into a multilayered rumination on the much more richly layered and complex matter of the human condition.

As you explained, the book focuses on Alan Dudley's collection of skulls, and within the book you give a little background on the man and his unusual hobby. What was his role in the creation of the book?

As you explained, the book focuses on Alan Dudley's collection of skulls, and within the book you give a little background on the man and his unusual hobby. What was his role in the creation of the book?

Alan was tireless in his enthused cooperation--after all, few people had paid much attention to what many thought was a somewhat weird, perhaps even slightly creepy hobby. His wife--from whom he became estranged--did not greatly like it, most especially when he returned from the somewhat aromatic processes that are involved in stripping flesh from skulls, and which Alan accomplished in his garden shed. His neighbors did not understand, nor even truly know what he did, nor of the world-class trove he had assembled in the upstairs bedroom of his very modest and outwardly unremarkable home. The only serious attention Alan had ever won turned out to have come from the police, who came to his door one day armed with a search warrant, crime-scene tape (which they strung across the entrance to his bedroom, thus denying him access to his collection) and an electronic ankle bracelet. But then we came along, and when we asked him to help us turn his story into a publishable account, he was hospitality personified. He especially took great pains to see that all the needs of our photographer, Nick Mann, were met, day after day, as a complete photographic record of the collection was laboriously assembled, with Nick using complex high-tech contrivances such as Alan had never seen before. In short, Alan Dudley loved helping, and is very proud of what we have done, in managing to show off his achievement to the world. This is Alan's book, every bit as much as ours.

Tell us about your process for choosing the species and the images.

Tell us about your process for choosing the species and the images.

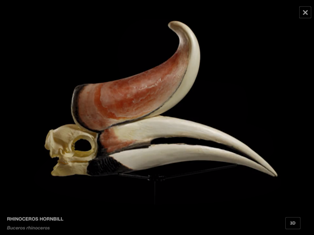

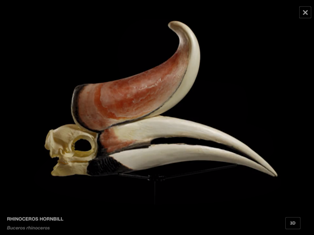

First, we wanted the species to range as widely as possible across the five basic classes of the chordate phylum: we wanted to show a wide sample of the various fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals that Alan had in his collection. Once we had assembled a sufficient number from each class (or "superclass"--taxonomy has become a very much more complicated art than when I was at school), we then picked the specimens we would use in the book on the basis of a very simple criterion: how attractive and interesting-looking was each one. Moreover, since we also planned to include images of each animal to which a skull belonged, we wanted both the animal and its skull to be interesting-looking. Hence a mandrill, a wombat, a gaboon viper--all wonderful in life, stunning in death.

Prior to the print version from Black Dog & Leventhal, Touch Press created an app for Skulls, and you narrate some of the activity in it. Tell us about your experience with that process.

This was an app, built for the iPad, by the very friends in London--most notably Max Whitby, the founder of Touch Press--who had alerted me to Alan Dudley's strange story in the first place. Max and his team--flushed by the recent grand success of their apps relating to Elements and The Solar System--took rather more than a year to create the most extraordinary app, with Alan's skulls brought vividly to life (as it were!) by the rotational and expandable possibilities of Nick Mann's photography. This book is one of the first ever to have been created in the aftermath of its initial publication as an app. The critical reaction to the app was overwhelmingly positive, and we are now hoping that the interest in our book may yet spawn further interest in the app itself. I will be using the app to illustrate the book during my talks, which is in itself a rather unusual form of cross-fertilization.

You talk about the importance of education and how you want Skulls to be a tool for education. If you could have every reader of the book walk away with one overall idea or concept from the book, what would you hope they take away from it?

Wise men say--or at least, will argue--that all mature decisions should be made with the head rather than the heart. This book explains and illustrates just why: why the head and all that it contains is so revered, by all, and for all past time. This book sweeps aside the macabre, and places the head and the skull where it should properly be: in prime position, as the most important part of every body, and for everybody, and for always. --Jen Forbus of Jen's Book Thoughts

Simon Winchester: The Skull in Prime Position

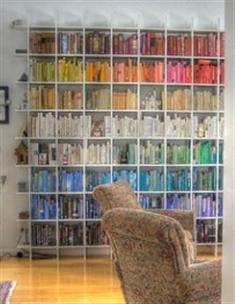

We wondered, on Twitter and Facebook, how you shelve your books. A good number of you don't organize at all (Deborah wrote: "very randomly--life's more adventurous that way"), while most stick with the tried-and-true alphabetical; shelving by color is popular, too. @bookletting replied: "1st, by when I read them." @Peacock10 does it "By height. Tall to short then to tall again. My eye needs symmetry." And @StaceyLMason organizes "by how a book made me feel."

We wondered, on Twitter and Facebook, how you shelve your books. A good number of you don't organize at all (Deborah wrote: "very randomly--life's more adventurous that way"), while most stick with the tried-and-true alphabetical; shelving by color is popular, too. @bookletting replied: "1st, by when I read them." @Peacock10 does it "By height. Tall to short then to tall again. My eye needs symmetry." And @StaceyLMason organizes "by how a book made me feel."

As you explained, the book focuses on Alan Dudley's collection of skulls, and within the book you give a little background on the man and his unusual hobby. What was his role in the creation of the book?

As you explained, the book focuses on Alan Dudley's collection of skulls, and within the book you give a little background on the man and his unusual hobby. What was his role in the creation of the book? Tell us about your process for choosing the species and the images.

Tell us about your process for choosing the species and the images.