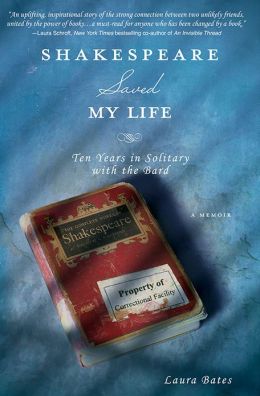

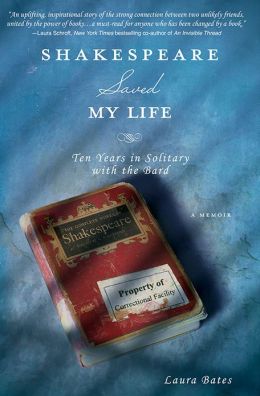

Laura Bates, a Chicago native, has a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago with a focus on Shakespearean studies. She has taught Shakespeare at Indiana State University for more than 15 years. Concurrently, she has also worked in prisons, first as a volunteer and later as a professor. She is the creator of a program called Shakespeare in Shackles (you can watch her TED Talk about it here), which introduces Shakespeare's works to prisoners in both the general population and in supermax (the long-term solitary confinement unit). Bates, and her work with Shakespeare in Shackles, has been featured in local and national media, including MSNBC-TV's Lock Up. Bates is the author of Shakespeare Saved My Life: Ten Years in Solitary with the Bard, just published by Sourcebooks (see our review below).

Laura Bates, a Chicago native, has a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago with a focus on Shakespearean studies. She has taught Shakespeare at Indiana State University for more than 15 years. Concurrently, she has also worked in prisons, first as a volunteer and later as a professor. She is the creator of a program called Shakespeare in Shackles (you can watch her TED Talk about it here), which introduces Shakespeare's works to prisoners in both the general population and in supermax (the long-term solitary confinement unit). Bates, and her work with Shakespeare in Shackles, has been featured in local and national media, including MSNBC-TV's Lock Up. Bates is the author of Shakespeare Saved My Life: Ten Years in Solitary with the Bard, just published by Sourcebooks (see our review below).

You mention in your book that you grew up poor in an inner-city ghetto, and that criminal activity was common among your adolescent peers. Many prisoners report similar circumstances. Why do you think you were able to take a different path into adulthood than the prisoners you've taught?

I was lucky enough to be unpopular. What I mean by that is, while criminal activity was common in my neighborhood and among my peers, I was more of an observer than a participant. In addition to keeping me out of prison, that had another happy result: I was already honing my powers of observation, an important skill for an author.

You first read Shakespeare at age 10. Do you remember how you became passionate about him, and when you realized that teaching Shakespeare to others would be your life's work?

You first read Shakespeare at age 10. Do you remember how you became passionate about him, and when you realized that teaching Shakespeare to others would be your life's work?

To be honest, I can't say that I "read" Shakespeare at age 10, but I did buy a copy of Macbeth from our local bookstore just because I was so intrigued by this classic literature that seemed so out of reach. Somehow even at that age, I knew it was worth reaching for. Like most students, I learned to read Shakespeare in high school, starting with Julius Caesar. But the passion didn't really develop until I started to write plays myself. Forty-five years after I bought that first book, I am still reading Macbeth, and finding something new in it every year.

You went back to school to finish your B.A. (and continued on to a Ph.D.) as an older student. Do you think that your work experience allowed you additional insight into the writings of Shakespeare as you returned to the classroom?

I was 30 years old, with two stepchildren attending Columbia College, when I returned to finish the B.A. that I had abandoned 10 years earlier to begin working full time in publishing. For three years I was the theater editor for Chicago magazine; during that time I attended many Shakespeare plays. That experience as a spectator, coupled with my own experience as a playwright, provided additional insight that traditional college students did not have, and it did make me appreciate Shakespeare more.

Though this is mentioned briefly in your book, would you expand on your decision to start teaching Shakespeare to prisoners and why the work of the Bard might be so important to that particular population?

My work in prison began as a result of an argument with a friend of my husband who was doing theater work with maximum-security prisoners. At the time, I felt that these hardcore criminals were beyond rehabilitation, that such efforts should be directed to first-time offenders. To test out my own theory, I started to do theater work with inmates. My decision to bring Shakespeare to these prisoners was the result of another argument, this time with an internationally respected Shakespeare scholar who claimed that Macbeth represented "the ipso facto valorization of transgression." I wondered if real-life transgressors would agree, and I went into supermax to find out. The more insight that prisoners get into Shakespeare's characters, the more insight they get into their own character. At the same time, the prisoners' interpretations of the plays are unique and fresh, and that is valuable for scholars--or anyone who is interested in a new way of looking at Shakespeare.

Despite the very different settings of the college classroom and solitary confinement, you were able to merge your teaching experiences to some extent. What was it like to teach students in such divergent circumstances at the same time?

Schizophrenic! What they had in common was Shakespeare, and my basic approach, which was to encourage students to make personal connections to the text. But the connections they made were very different. Where prisoners related to Macbeth's murder, campus students related to his nagging wife. Where prisoners understood the gang violence that leads Romeo to a revenge killing, campus students were more familiar with teenage love.

|

| Bates with inmates in the solitary confinement unit. |

In your book, the descriptions and images of you sitting in the hallway, teaching Shakespeare to prisoners in solitary confinement, are striking. You could only glimpse their faces or hands through the handcuff portals during your sessions. Did you find the teaching experience different without the ability to use body language as feedback?

Different, but not necessarily more difficult. In a way, it was even more engaged precisely because the body language was so intensely focused. Eyes can speak volumes. So can a hand waving wildly to capture my attention or smacking the cuff port to punctuate a comment.

Your book is essentially a combined memoir since it tells your story in parallel to that of an incarcerated student, Larry Newton. When did you realize that this book would need to be about both of you?

The book started with Larry's story, and I added the chapters in which my life parallels Larry's later. I collected hundreds of hours of our conversations on audio and video recordings during the 10 years that we worked together, writing handbooks to 13 of Shakespeare's plays. I told him then that I wanted to write a book about his transformative journey through Shakespeare. He trusted me to tell his story--and he provided the title for the book. When I asked him what Shakespeare had done for him, he replied, "Shakespeare saved my life." --Roni K. Devlin, owner, Literary Life Bookstore

Laura Bates: Saving Lives Through Shakespeare

Laura Bates, a Chicago native, has a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago with a focus on Shakespearean studies. She has taught Shakespeare at Indiana State University for more than 15 years. Concurrently, she has also worked in prisons, first as a volunteer and later as a professor. She is the creator of a program called Shakespeare in Shackles (you can watch her TED Talk about it

Laura Bates, a Chicago native, has a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago with a focus on Shakespearean studies. She has taught Shakespeare at Indiana State University for more than 15 years. Concurrently, she has also worked in prisons, first as a volunteer and later as a professor. She is the creator of a program called Shakespeare in Shackles (you can watch her TED Talk about it  You first read Shakespeare at age 10. Do you remember how you became passionate about him, and when you realized that teaching Shakespeare to others would be your life's work?

You first read Shakespeare at age 10. Do you remember how you became passionate about him, and when you realized that teaching Shakespeare to others would be your life's work?