Born in Chicago in 1935, William Friedkin admits in The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir (see our review below) that as a young boy growing up he had no moral compass. ("I may have sugar-coated it in the memoir.") But a mother's love for her child turned him around and he went on to become a celebrated movie director. Two of his films are among the most influential and successful movies ever made: The French Connection, which won him an Oscar for Best Director (the film won Best Picture), and The Exorcist. Forty years after its release, the latter is still the highest grossing horror film of all time--he prefers to see it as a film about the "mystery of faith."

Shelf Awareness interviewed Friedkin by telephone from his office in Los Angeles.

Here you are in your late 70s, and you've finally written a memoir about your career and your films. What took you so long?

An agent, Richard Pine, called me and asked if I'd be interested in writing my autobiography. I said no. He said, why not? I said because I wouldn't be interested in reading it. He told me he had five publishers interested. So now I was interested. I flew to New York and talked to them. Jonathan Burnham of HarperCollins told me to write about my feelings, write about things that were important to me. And that was the key; it opened the door for me. It meant writing with extreme candor, so I interviewed a number of people I worked with who are still around and I got their sense of the work we had done together. They often conflicted with my own memories, like Kurosawa's Rashomon. These helped me sort out my own memories. I wrote the book in longhand over three years in Moleskine books. I sent the pages to my editor and we got it done.

What was it like working with Sonny and Cher on your first film, Good Times?

I cared about them. We were contemporaries. I wasn't a fan of their music (I like classical and jazz), but I got to see how Sonny worked and I was extremely impressed. I liked and respected him enormously. At that time Cher was mainly a hanger-on, not really sure of what she wanted to do. A child of the Sunset Strip. Sonny took her and molded her. It's very much a Pygmalion story. We had the same sense of humor, which is one of the best ways to get to know somebody.

Would you recount the story about how you almost missed the Oscar ceremony in which you were up for Best Director for The French Connection?

Back then the ceremony was at the Music Center in downtown L.A., and traffic was always heavy. Six of us in evening dress left in my business manager's Rolls Royce. It broke down. We pushed the car into a nearby service station. The car was dead. No cabs, of course. There was a guy in a funky little Ford, and I asked him if he could give us a lift to the Music Center. "I'll make it worth your while. I have a film nominated for best picture tonight, The French Connection, and I'm the director." He said, "okay, but you'll need to call my wife tonight, win or lose." I promised. I called her around midnight with the news that we had won. Our guardian angel saved the day. Frank Capra handed me the Oscar for Best Director that evening and whispered quietly: "Terrific, you deserved it."

You say that the chase scene is the "purest form of cinema." In what way?

The chase scene can't be done in any other medium. But through the use of montage in cinema you can. No dialogue needed. It's "pure cinema"--simplicity and clarity. You need surprises along the way. Highly visual, plus the soundtracks layered in afterwards can help enhance the audience's appreciation.

Next comes The Exorcist. You're on a creative roll. What was happening to you as a director that made you so successful at this time?

The French Connection led to The Exorcist, which was an extraordinary piece of material. There had been nothing like it prior, something about the literal power of the Christian faith. It made me think about other things in history that can only be explained by demonic possession, like the rise of National Socialism and Hitler. You can only explore this as a case of mass hysteria or demonic possession. A whole generation followed him into hell. So the material was exceptional, and by then I had learned much about my craft. I had confidence in my casts and my decisions.

Then came Sorcerer, a remake of the French classic Wages of Sin. You're pretty hard on yourself describing its failure.

I had thought that was my best film. In many ways, I still do. It's on the eve of a resurrection as we talk; it will be re-released by a major studio. I put some of my best work into it. It was a tough picture to make, illness and injury. It crashed and burned, way out of time with the zeitgeist--Star Wars.

In the memoir you "confess" you actually spent some of the counterfeit $20 bills you printed in To Live and Die in L.A.--"the money was that good." Do you think the Secret Service will be knocking on your anytime soon?

Not much. Back then I'd put a bill in my wallet with my money. I didn't want to deceive anyone. But as a test, the money was great. I confess this to show how good it was. Most of it was only printed on one side. I got a mouthful from the U.S. Attorney General of California. One of our special effects people took some of the one-sided bills home as a souvenir, and his son passed them around to friends. The Secret Service was down there in 10 minutes, and then they called me. They were very angry.

Can you talk a little bit about your enjoyment editing a film?

It's the most creative aspect of filmmaking. I think it's probably similar to composing music, where you hear some melodies and then start playing them. Everything you shoot on the set is just raw material for the editing room. I edit with a completely open mind about how I'm going to put the film together, move things around. No pressure. Editing should really be called composing.

Everyone has a top 10 list. From your memoir we learn you really admire Citizen Kane. What are some others?

It's very eclectic. All About Eve. The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Paths of Glory. Singing in the Rain. An American in Paris. Gigi. Blowup. There's a film made in the '70s that I think is even more relevant today--The Parallax View. Made by a director who passed away too early, Alan Pakula. I believe it's a masterpiece of the period. 8 1/2. Night of the Hunter. Antonioni's trilogy: L'Avventura, La Notte, L'eclisse. The films of the '50s and '60s are very important to me. Recently I discovered the silent films of Buster Keaton. They're masterpieces. I don't know how they did them. Brilliantly executed and life-threatening.

What's next? Any new projects out there you're excited about?

I'm looking at a number of things, including three operas to possibly direct and several film projects, but right now I'm looking forward to the book tour, meeting new people. I'll do a benefit reading in Chicago at the downtown library to which I owe so much, probably about $15,000 in book fines. I'm pleased I was able to get through the writing process. It never occurred to me that I could do it. It's been a surprise and delight. And I hope there will be a new Friedkin film--that's all in God's hands. --Tom Lavoie, former publisher

William Friedkin: The Film Director Connects with His Past

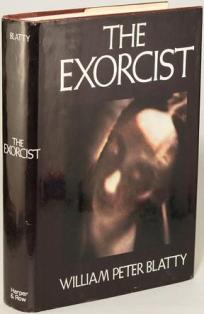

Then, because I'm a book person, I remembered a terrifying summer more than four decades ago when everybody was reading William Peter Blatty's novel. The Exorcist was my first official "beach read," and I was in very good company that summer; thousands of people, including more than a few self-proclaimed "nonreaders" I knew, were under its terrible/wonderful spell.

Then, because I'm a book person, I remembered a terrifying summer more than four decades ago when everybody was reading William Peter Blatty's novel. The Exorcist was my first official "beach read," and I was in very good company that summer; thousands of people, including more than a few self-proclaimed "nonreaders" I knew, were under its terrible/wonderful spell.