Tom Lichtenheld, the artist behind Steam Train, Dream Train by Sherri Duskey Rinker, just published by Chronicle Books, took time out of his book tour to answer a few questions and draw a few pictures.

Tom Lichtenheld, the artist behind Steam Train, Dream Train by Sherri Duskey Rinker, just published by Chronicle Books, took time out of his book tour to answer a few questions and draw a few pictures.

We understand that you've been drawing for as long as you can remember. Did you have a favorite theme in your early drawings? A favorite place to draw? Can you show it to us?

The first thing I remember drawing was a ship, and I recall drawing lots of cars (Mustangs and Jaguar XKEs, to be specific) during social studies class in eighth grade.

Of course, I do a lot of drawing in my studio, but there's another place I find strangely inspiring, which is everywhere except my studio. In particular, I like to doodle and work out story problems when I'm at some sort of public performance, like a concert or school play--the more mediocre the performance, the better. There's something stimulating about having my attention divided. I think it's like drawing in your dreams, where your subconscious is allowed to wander on its own.

I drew this woman during a reading at my local library. The story being read was excellent but dark, so her expression reflects the mood in the room.

You've done two books with Sherri Duskey Rinker that are home-run themes with children--construction sites and trains. What is it like to collaborate with her?

With the first book, there was more back-and-forth with the editor than Sherri, but we collaborated quite a bit on the second one. Sherri's an artist as well, so we speak the same language, and she's very open to my spin on things.

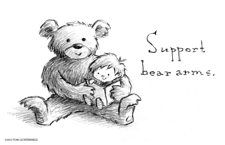

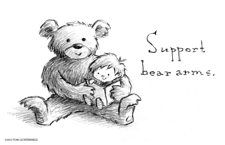

"I heard about the Newtown shootings while sitting in a coffee shop. Like everyone else, I was filled with sadness and anger, so I did this drawing as much for therapy as anything else."

"I heard about the Newtown shootings while sitting in a coffee shop. Like everyone else, I was filled with sadness and anger, so I did this drawing as much for therapy as anything else."

What is your process when you're working on a book?

If I'm considering a manuscript from someone else, the first thing I do is quickly doodle in the margins of the manuscript. If a few good images come to me quickly, I know the book is clicking with me, so I sit down and spend a few hours on loose sketches. This initial work is very important because it tells me if I'm excited about the book. Then I paginate the story a few different ways; not for technical reasons, but to see if I can bring some rhythm and dynamics to the idea. Eventually, the entire book gets sketched out into a storyboard and the real illustration work begins.

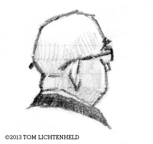

"I drew this in church, where I do a lot of 3/4-from-behind drawings. It's here I realized that ears are really funny-looking."

"I drew this in church, where I do a lot of 3/4-from-behind drawings. It's here I realized that ears are really funny-looking."

Which artists have most influenced you?

My artist and illustrator heroes are a diverse bunch because I know just enough about art to understand the genius behind what artists do but lack the talent to do most of it myself. Fundamentally, I admire great drawers, great painters and artists who do great goofy stuff.

A few of the great drawers I admire are Peter de Seve, Eric Rohmann and Marla Frazee.

I'm more of a drawer than a painter myself, so I'm in awe of painters like John Singer Sargent, Grant Wood, and Winslow Homer.

In the goofy category, I love everything done by Oliver Jeffers. He's more witty than goofy, but his work makes me smile, and he's also a fabulous painter. My go-to goofy artist is Delphine Durand, whose book My House is an endless source of inspiration.

"This was drawn at a local film festival, while waiting for the projectionist to figure out the new-fangled digital projector. When in doubt, draw a dog."

"This was drawn at a local film festival, while waiting for the projectionist to figure out the new-fangled digital projector. When in doubt, draw a dog."

What are your favorite things to draw when you're not working on a book project?

Mostly people, but I also like to draw animals and simple objects. When I worked in advertising, I drew a lot of feet because it was the only part of people I could draw during meetings without them noticing.

This is one of hundreds of drawings I've done of shoes while sitting in boring meetings about advertising. No, I don't have a foot fetish, it's just the only thing I could look at without getting busted for not paying attention.

This is one of hundreds of drawings I've done of shoes while sitting in boring meetings about advertising. No, I don't have a foot fetish, it's just the only thing I could look at without getting busted for not paying attention.

What are your favorite things to do when you're not drawing?

Talking with other book creators, goofing off with nieces and nephews, riding my bike, eating chocolate.

"I can't remember where I drew this, but I know it wasn't in my studio or I wouldn't have used a dried-up brush pen--yet it's so much better this way."

"I can't remember where I drew this, but I know it wasn't in my studio or I wouldn't have used a dried-up brush pen--yet it's so much better this way."

Tom Lichtenheld: 'When in Doubt, Draw a Dog'

Tom Lichtenheld, the artist behind Steam Train, Dream Train by Sherri Duskey Rinker, just published by Chronicle Books, took time out of his book tour to answer a few questions and draw a few pictures.

Tom Lichtenheld, the artist behind Steam Train, Dream Train by Sherri Duskey Rinker, just published by Chronicle Books, took time out of his book tour to answer a few questions and draw a few pictures.

"I heard about the Newtown shootings while sitting in a coffee shop. Like everyone else, I was filled with sadness and anger, so I did this drawing as much for therapy as anything else."

"I heard about the Newtown shootings while sitting in a coffee shop. Like everyone else, I was filled with sadness and anger, so I did this drawing as much for therapy as anything else." "I drew this in church, where I do a lot of 3/4-from-behind drawings. It's here I realized that ears are really funny-looking."

"I drew this in church, where I do a lot of 3/4-from-behind drawings. It's here I realized that ears are really funny-looking." "This was drawn at a local film festival, while waiting for the projectionist to figure out the new-fangled digital projector. When in doubt, draw a dog."

"This was drawn at a local film festival, while waiting for the projectionist to figure out the new-fangled digital projector. When in doubt, draw a dog." This is one of hundreds of drawings I've done of shoes while sitting in boring meetings about advertising. No, I don't have a foot fetish, it's just the only thing I could look at without getting busted for not paying attention.

This is one of hundreds of drawings I've done of shoes while sitting in boring meetings about advertising. No, I don't have a foot fetish, it's just the only thing I could look at without getting busted for not paying attention. "I can't remember where I drew this, but I know it wasn't in my studio or I wouldn't have used a dried-up brush pen--yet it's so much better this way."

"I can't remember where I drew this, but I know it wasn't in my studio or I wouldn't have used a dried-up brush pen--yet it's so much better this way."