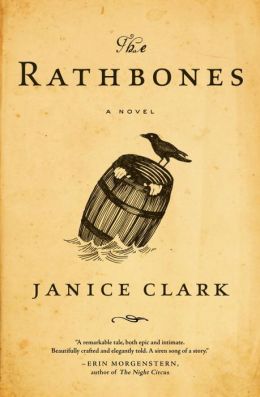

Janice Clark is a writer and designer living in Chicago. She grew up in Mystic, Conn., home of Mystic Seaport and the famous whaleship Charles W. Morgan. She's also lived in Montreal, Kansas City, San Francisco and New York, where she earned an MFA in writing at New York University. Her short fiction has appeared in Pindeldyboz and the Nebraska Review and her design work is represented in the Museum of Modern Art. The Rathbones (just published by Doubleday; see our review below), which she also illustrated, is her first novel. (Watch the trailer for the book here.)

Janice Clark is a writer and designer living in Chicago. She grew up in Mystic, Conn., home of Mystic Seaport and the famous whaleship Charles W. Morgan. She's also lived in Montreal, Kansas City, San Francisco and New York, where she earned an MFA in writing at New York University. Her short fiction has appeared in Pindeldyboz and the Nebraska Review and her design work is represented in the Museum of Modern Art. The Rathbones (just published by Doubleday; see our review below), which she also illustrated, is her first novel. (Watch the trailer for the book here.)

This is a big, ambitious and impressive first novel. It comes upon the reader like a breeching whale. What's the background to its genesis and writing?

The Rathbones started as a short story about 10 years ago, and I began developing it while in the MFA program at NYU. The novel took seven years to write. I think part of the reason for its ambition was that I came to writing late, with a few more decades of life to draw on than most debut novelists. As a divorced single parent raising a son on my own and running a small graphic design office, I had no time to devote to fiction, though I had loved writing when younger. After my son started college, I took a writing class and was hooked.

How much of an impact did growing up in Mystic have on your writing of the novel? And where did the Rathbone name come from?

Growing up near Mystic Seaport, a whaling museum, I of course wasn't at all interested in whaling and didn't become interested until I read a few books about the sperm whale as an adult. I've lived most of my life far from the ocean, always longing for it--though it wasn't a defined goal, writing about whaling kept me connected to the sea in a vital way. I grew up in a mid-century modern house in a town known for its 18th- and 19th-century architecture, and had always loved Mystic's austere Greek Revival houses perched on hills, many topped with widows' walks. There's also a wonderfully Gothic Victorian house in Noank, Conn., that in part inspired Rathbone House; local legend holds it to have been owned at one time by Charles Addams.

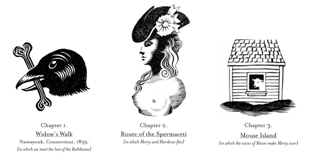

The novel's original title was Crow. Mercy Rathbone sends her surviving pet crow (its twin having met with a crushing end) off to witness scenes from the dark history of the Rathbone family. As the story ventured further and dived deeper into the family's history, the novel began to call for a more epic title, hence The Rathbones.

One of the great pleasures of The Rathbones is entering into the amazing, old New England fictional world you've created. How difficult was it to create this detailed world?

One of the great pleasures of The Rathbones is entering into the amazing, old New England fictional world you've created. How difficult was it to create this detailed world?

I love research--I can get lost for hours and feel only low-level guilt because, after all, I'm working; it's sometimes hard for me to tear myself away and do the hard work of actually writing. For me, it's less a question of achieving a detailed world than not becoming overwhelmed by detail. I'm not looking to place the reader firmly in a "historical fiction" past that's strictly matchable to a time and place, but to a fictional world that, though somewhat grounded in reality, has its own rules and its own reality.

Where did your great main character and primary narrator, 15-year-old Mercy, the "small and dark," come from?

Though my mother never walked a widow's walk, she was always waiting for my father--who was in the Navy when I was child--to return from sea. There's a little of Mercy in me in that I felt my mother's attention so often turned elsewhere. Since I always had my nose in a book as a child, and a proclivity for the dark and troubling, there's probably a little Jane Eyre and Wednesday Addams in there, too.

Our family, like all Navy families, moved frequently, and there's a story that my oldest sister slept in a dresser drawer for a while, before furniture from the latest move arrived; I think Mercy's diminutive size came in part from this. But the "small and dark" also gestures at how unformed Mercy is at 15, having known such a sheltered life in Rathbone House; as she moves out into the light and air on her adventure she lightens and lengthens.

I also worked with the ideas of "dark" and "light" to paint in broader strokes: the small and dark Rathbones are compact, nimble, connected to nature and the sea; the long and golden Starks attenuated and weakened. The family patriarch, Moses Rathbone, "knew that the blood of the golden wives had thinned the Rathbone veins, had stiffened their sea legs and bled their dark strength to white."

Moby Dick has to have been an influence, what with Moses riding on the backs of whales, Ahab-like, harpoon drawn.

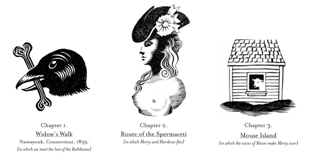

Definitely. Moby Dick is for me the greatest American novel; nothing else comes close to the deep and rich strangeness of Melville. I've always loved Rockwell Kent's illustrations for the 1930 edition of Moby Dick; I drew the little illustrations that head each chapter in homage to Kent.

What other books influenced you?

The Odyssey was a major influence. Also the Patrick O'Brian Aubrey/Maturin novels, which I love not for their 19th-century naval battles, but for their characters, particularly Stephen Maturin, whose enthusiasm for natural science shows up in somewhat twisted form in Mordecai Rathbone; and for the spirit of high adventure. Though The Rathbones aspires to a larger story about America--our exploitation of nature; the immense resources and immense greed possible only in a continent so vast and so rich--my hope was to couch the cautionary tale in an adventure story. Many readers I know, most of them women, are weary of delicate domestic dramas. They may love Jane Austen but they also love Game of Thrones.

The book is a fascinating mix of realism and magical realism. It's not every day we read about crows lifting up a small girl by her braids. Can you talk about your genre-bending narrative?

I didn't really think about genre. I just knew that I wanted it to ride that divide between the possible and the improbable; there's a tension there, a liminal place, that I find exciting.

This is a rather dark and dangerous gothic novel. How did you come up with the style and tone?

I joke that writing is my substitute for therapy, but I'm only sort of joking. I'd much rather plumb my dark and disturbed inner life for story than fully understand myself. The half-seen and half-understood is always more exciting. Judging by early reactions to the book, there are many more equally dark and disturbed readers out there than I would have guessed.

Moses Rathbone, the family patriarch, the bringer of children, the man who seems part whale--where did he come from?

Though the novel suggests that Moses may be a Native American or Inuit from somewhere to the north, I didn't want to put in the foreground issues of race but rather to suggest that Moses is a man deeply connected to nature, to the whales and the sea; he's the ground zero of the Rathbone family's arc from one-with-nature to emptied out, spermless and dry.

And Mordecai, Mercy's loyal cousin, who counsels her and accompanies her on her odyssey?

Mordecai is the nadir of the family's sad trajectory from powerful to weak. Up in his attic in Rathbone House under the hull of a whaling ship, he instructs Mercy in those things her mother--busy carving her whale bones--should have taught her: lessons in deportment, the proper pouring of tea. Along with the other mysteries of the novel--why Papa has been gone so long, what happened to Mercy's brother, why Mama is so cold--the reasons for Mordecai's exile in the attic with his specimens and logbooks are at the heart of the story.

The image of bones is a key one in the novel. How did that image develop?

The image of bones is a key one in the novel. How did that image develop?

In working on the novel I spent many hours looking at scrimshaw--whalebone artifacts, carved by sailors in their months and years at sea: delicate portraits incised in great sperm whale teeth; jagging wheels and carved cricket cages and busks for corsets. And also from two Grimm tales, "The Singing Bone" and "The Juniper Tree," in both of which long-hidden bones, uncovered, sing of their misfortune.

Where did that strange song about the "mother who murdered me" that appears here and there throughout the novel come from?

"Father, Father" was inspired by the heft and sorrow of old English ballads. I think there's also a little of the wonderfully creepy Victorian poet Thomas Lovell Beddoes in there. I wrote a tune for the song, and sang it often while writing.

The use of the slowly developing Rathbone family tree illustration is a beautiful touch.

I first drew the family tree to help myself navigate the complicated genealogy of the family, then thought that successive reveals, as Mercy and Mordecai uncover more and more of the Rathbone past, would be fun as well as helpful to the reader. It was so much fun drawing the little portraits that augment the often unsavory details of the Rathbone family tree.

What are you working on now?

I'm working on a novel in which trees are as important as whales were to The Rathbones. It begins with 13 lumberjacks who live in the trees and never come down. --Tom Lavoie, former publisher

Janice Clark: Whalebone and Crow

Paula McLain's The Paris Wife presents the story of Ernest Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley. Though history spoils the ending a bit--knowing that Hadley was Hemingway's first wife implies the inevitable dissolution of their marriage--the novel is a touching tale of intimacy and of Paris in the 1920s.

Paula McLain's The Paris Wife presents the story of Ernest Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley. Though history spoils the ending a bit--knowing that Hadley was Hemingway's first wife implies the inevitable dissolution of their marriage--the novel is a touching tale of intimacy and of Paris in the 1920s. Only a decade or so before the Fitzgeralds took the world by storm and Ernest and Hadley moved to Paris, Mamah Cheney shocked Chicago society by leaving her husband and children to pursue an affair with architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Loving Frank, Nancy Horan's debut novel, brings this little-remembered figure back to life, positing that Cheney had a considerable amount of influence on Wright's work even as she herself struggled to find a voice for her own creativity in an era not known for its feminist ideals.

Only a decade or so before the Fitzgeralds took the world by storm and Ernest and Hadley moved to Paris, Mamah Cheney shocked Chicago society by leaving her husband and children to pursue an affair with architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Loving Frank, Nancy Horan's debut novel, brings this little-remembered figure back to life, positing that Cheney had a considerable amount of influence on Wright's work even as she herself struggled to find a voice for her own creativity in an era not known for its feminist ideals. The Aviator's Wife focuses on Anne Morrow, wife of Charles Lindbergh. Author Melanie Benjamin follows the arc of their relationship from early courtship through the loss of their son to their fallout over political differences, revealing details not only of an oft-troubled marriage, but of a woman strong enough to maintain her own identity through it all. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

The Aviator's Wife focuses on Anne Morrow, wife of Charles Lindbergh. Author Melanie Benjamin follows the arc of their relationship from early courtship through the loss of their son to their fallout over political differences, revealing details not only of an oft-troubled marriage, but of a woman strong enough to maintain her own identity through it all. --Kerry McHugh, blogger at Entomology of a Bookworm

One of the great pleasures of The Rathbones is entering into the amazing, old New England fictional world you've created. How difficult was it to create this detailed world?

One of the great pleasures of The Rathbones is entering into the amazing, old New England fictional world you've created. How difficult was it to create this detailed world? The image of bones is a key one in the novel. How did that image develop?

The image of bones is a key one in the novel. How did that image develop?