|

| photo: L.E. Baskow |

Charles D'Ambrosio has published two collections of short stories, The Point and The Dead Fish Museum, of which Michael Chabon wrote: "No one today writes better short stories than these." He has a new collection of essays, Loitering: New and Collected Essays (see our review below). D'Ambrosio was born and raised in Seattle and now lives in Iowa City, Iowa, where he teaches fiction at the Iowa Writers' Workshop.

How did Loitering come about?

If you're talking about the writing itself, it came about just like my grocery lists, one word at a time. If you're asking about the book itself, I can say that it has something of a checkered history, but that ultimately Loitering evolved quite naturally out of a longstanding relationship with Tin House and the people who make that great magazine and writing conference and book-publishing venture hum. Two years ago I was invited by the Tin House Writer's Conference to participate on a panel about nonfiction, and because I sat on that panel, jawing on about the personal essay, I decided it was only right to give a reading from one of my essays. Afterward, people were asking where they could get the book, but there was no book, and not too long after that Tony Perez, my editor, contacted me. At first we talked about simply reissuing Orphans, a small press edition of some of the essays, but that conversation quickly expanded and so did the scope of the book, which now gathers new and uncollected work and is, I believe, truer to the range of things that I think and write about.

In your "By Way of a Preface" you describe the essays as a kind of container, the "thing that caught and held words like holy water, offering the gift of awareness." Where did this fascination for the genre come from?

It probably came from several lucky encounters. The first was a small bookstore across the street from the stop where I always caught the bus home. The place stayed open late, and at first I went in there only to keep warm, but the women who owned it would ask what I was looking for, and of course I didn't know, so they'd recommend books they were high on. They were high on M.F.K. Fisher, and that got me going. The second lucky encounter took place in an Intro to Lit class I took as a freshman at the University of Washington. I had this great teacher, Helen Menke--years later I would realize she was only a grad student, a TA, but she was a life-changer for me--who put me on to Edward Abbey and Joan Didion. And the last lucky encounter was with the Sunday New York Times, which my father, a professor of finance, subscribed to for the business section. In the Book Review one week there was a piece on cinephile culture by a woman named Susan Sontag. I'd never heard of her, but I liked the way she wrote. She sounded smart. Of course she was smart, but I had no basis for understanding that at the time. I immediately bought Against Interpretation and Styles of Radical Will, and when I dropped out of college, for those two years, Susan Sontag was my teacher. Everything she read, I read. Everything she liked, I liked. I was so caught up in the slipstream of Sontag's passions, and so without other forms of motivation or guidance, that I can now say I've watched a 10-hour movie about Hitler, some of it done with puppets. I was 19. The movie showed to a nearly empty house on two successive nights. I went both nights and ate a lot of jelly beans and popcorn.

Your essays always seem to involve you. Do they start out that way, or do you find yourself "discovering" something autobiographical about yourself or your family as you write?

Your essays always seem to involve you. Do they start out that way, or do you find yourself "discovering" something autobiographical about yourself or your family as you write?

Well, this is a book of personal essays, so of course I'm involved. As for autobiography, by my count there are only two pieces that deal directly with my family, one called "Documents" and another called "This Is Living." Otherwise, I write, in a personal way, about my hometown, Seattle, circa 1974, whaling, riding freight trains, manufactured homes, gambling and gamblers and brick, a Pentecostal haunted house, a vacant lot/eco-village in Austin, Tex., Russian orphans, The Catcher in the Rye, Mary Kay Letourneau, Richard Brautigan, showing up as a character in someone else's novel, 9/11 and a poem by Richard Hugo, and a few other things. The book is a kind of omnium-gatherum of my concerns. You can discover yourself in all kinds of ways, it seems to me, and dwelling on your family is only one of them.

Has an essay ever turned into a story?

No, the head spaces are so different, the demands of each form so unique, that I can't imagine transcoding an essay into a story. However, I can easily imagine "essayistic" fiction, and I don't believe the line that separates fiction and non is nearly as strict as we might think. I like the seams, but I also like the seams when they tear and fray.

Who are some of the masters of the essay you admire? Do you find their work influencing your own?

I could drop names, a ton of them, but in the end I'm a creature of the alt-weekly, and in Seattle the Stranger gave me a start, providing the space and the freedom, the permission to go at things in my own way--and that was as much of an influence on my work as any shelf of writers I could name. --Tom Lavoie, former publisher

Charles D'Ambrosio: Loitering with Intent

Your essays always seem to involve you. Do they start out that way, or do you find yourself "discovering" something autobiographical about yourself or your family as you write?

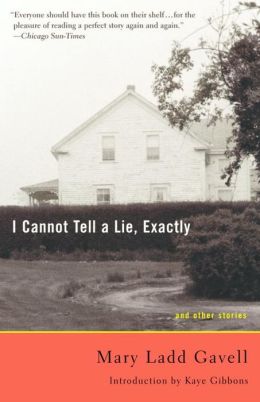

Your essays always seem to involve you. Do they start out that way, or do you find yourself "discovering" something autobiographical about yourself or your family as you write? When Mary Ladd Gavell died in 1967, she was a 47-year-old unpublished writer and managing editor of Psychiatry magazine, which ran her story "The Rotifer" as a memorial. Calling it a "gem," John Updike included "The Rotifer" in The Best American Short Stories of the Century (Vintage, 2000). A year later, the publication of I Cannot Tell a Lie, Exactly: And Other Stories (Random House) finally introduced readers to Gavell's fierce yet subtle narrative voice and her intriguing cast of characters, who often smile politely through masks that never quite cover their terror and misunderstanding of life's cruel ironies. In "Baucis," for example, a woman struggling to care for her demanding and sickly husband fantasizes about being a widow, but instead becomes ill herself. The woman's last words--"I didn't want to die first"--are mistakenly interpreted by her sons as a noble lament. Rediscovery seems inadequate for Gavell's brilliant stories. Unearthing "buried treasure" is more apt.

When Mary Ladd Gavell died in 1967, she was a 47-year-old unpublished writer and managing editor of Psychiatry magazine, which ran her story "The Rotifer" as a memorial. Calling it a "gem," John Updike included "The Rotifer" in The Best American Short Stories of the Century (Vintage, 2000). A year later, the publication of I Cannot Tell a Lie, Exactly: And Other Stories (Random House) finally introduced readers to Gavell's fierce yet subtle narrative voice and her intriguing cast of characters, who often smile politely through masks that never quite cover their terror and misunderstanding of life's cruel ironies. In "Baucis," for example, a woman struggling to care for her demanding and sickly husband fantasizes about being a widow, but instead becomes ill herself. The woman's last words--"I didn't want to die first"--are mistakenly interpreted by her sons as a noble lament. Rediscovery seems inadequate for Gavell's brilliant stories. Unearthing "buried treasure" is more apt.