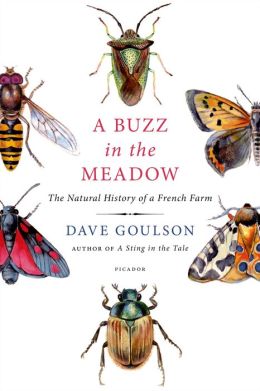

Dave Goulson is a British biologist, conservationist and professor of biology at the University of Sussex. His book A Sting in the Tale, like a "dumbledore" (the old English name for bumblebee), touched on history and language and human nature. His new book is A Buzz in the Meadow: The Natural History of a French Farm (our review is below).

Dave Goulson is a British biologist, conservationist and professor of biology at the University of Sussex. His book A Sting in the Tale, like a "dumbledore" (the old English name for bumblebee), touched on history and language and human nature. His new book is A Buzz in the Meadow: The Natural History of a French Farm (our review is below).

There's a dose of medicine in this book, much like your last book, that agribusiness finds hard to swallow. The chapter on bumblebees discusses Colony Collapse Disorder, and some of the factors contributing to the problem. Short of overturning the entire agribusiness/pesticide/food management system worldwide, what steps can we take to prevent further damage?

Actually, I think that we really should try to overturn the entire system. The current model is enormously inefficient, with about 40% of the food we grow going to waste. It is causing wildlife to disappear, with extinctions occurring at 1,000 times the historic rate. It is also causing somewhere in the region of 100 billion tonnes of soil to be lost every year--about 15 tonnes per person on the planet. It contributes substantially to climate change. None of this is sustainable. If we don't want our grandchildren to starve, then we need a new approach. This need not be difficult; there are plenty of techniques for growing food that are sustainable. Just as an example, gardeners and allotment holders can get between three and 11 times as much food from their land as does an intensive farmer, while using only a fraction of the chemicals, and while supporting a diversity of wildlife. I think it is clear that we should be trying to move towards small scale, local, healthy food production.

On a lighter note, there's a lot of joy to be found in your books. You clearly have a love for the natural world. How did this awareness and appreciation develop?

On a lighter note, there's a lot of joy to be found in your books. You clearly have a love for the natural world. How did this awareness and appreciation develop?

I honestly don't know where my obsession with wildlife came from. It is almost as if it was my calling--from as early as I can remember, I've never been much interested in anything else. My parents weren't especially keen on natural history, but they were happy enough to encourage me, buying me identification books, butterfly nets, cages, pots and so on, and they didn't mind me keeping a menagerie of creatures in my bedroom. I'm exceedingly lucky to have managed to make a living from pursuing my childhood hobby.

In writing your books, whom did you look to for inspiration?

I was a great Gerald Durrell fan from an early age, loving to read about his early life growing up on Corfu, and as a young boy I desperately wanted to be him. I was also fascinated by his books describing his exotic expeditions as an adult to catch animals, from which his warmth, humour and passion for wildlife shine through--Two Singles to Adventure was a particular favourite. I was also influenced by Jean-Henri Fabre's Book of Insects from 1879--when I was quite young my father gave me a battered copy that he found in a secondhand bookshop, which I have to this day. I was immediately hooked by the beautiful watercolour illustrations of beetles rolling dung, crickets singing to a mate and potter wasps building their nests. Fabre was, in a sense, the father of modern entomology--he spent his long life studying the fascinating lives of the insects that lived in his native southern France, discovering much that was new to science, and he describes some of his favourites in this wonderful, affectionate tome. I was envious of both Durrell and Fabre, for they encountered creatures that seemed very exotic to me; mantises, cicadas, snakes and terrapins, animals that were not to be found in my native Shropshire in England. I desperately wanted to travel to see these and other fabulous beasts, and have since been very fortunate in having had the chance to visit many corners of the Earth in search of wildlife. However, one thing that this has taught me is that there is a great deal of wonder to be had, and much to be discovered, by watching the more commonplace creatures that live all around us. There is so much that we don't know about the lives of bumblebees, earwigs, ants, hoverflies and so on, even though they live their lives right under our noses, in our gardens, parks, sometimes even inside out houses. These marvellous little creatures are the real inspiration for my writing, and for my academic research. I do not think that I will ever lose the sense of excitement one gets when making new discoveries about the lives of these small but important creatures. --Matthew Tiffany, LCPC, writer for Condalmo and psychotherapist

Dave Goulson: A Natural Obsession

On a lighter note, there's a lot of joy to be found in your books. You clearly have a love for the natural world. How did this awareness and appreciation develop?

On a lighter note, there's a lot of joy to be found in your books. You clearly have a love for the natural world. How did this awareness and appreciation develop?