|

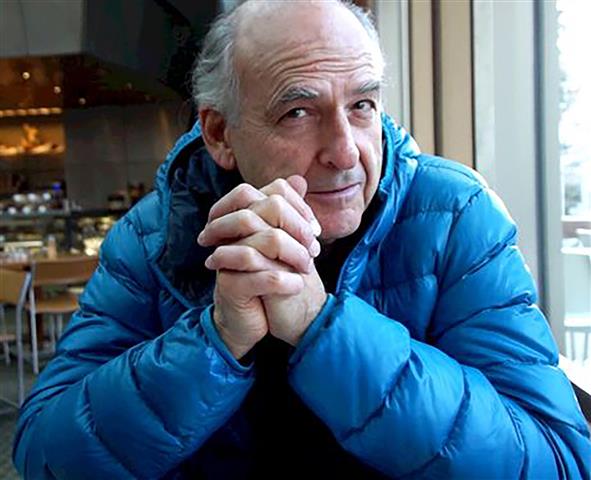

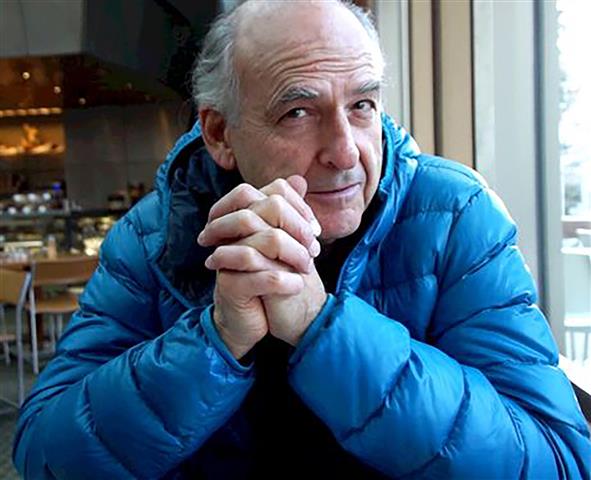

| photo: Louis Templado |

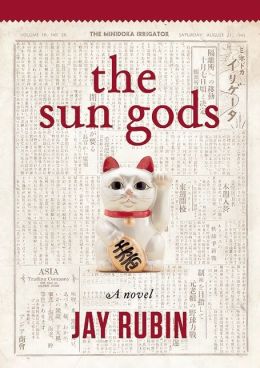

Jay Rubin received a Ph.D. in Japanese literature from the University of Chicago and is an English-language translator of Japanese literature, known best for his translations of Haruki Murakami's work. Rubin's first book, Making Sense of Japanese, has been used in Japanese-language courses around the world. His first novel is The Sun Gods (Chin Music Press, $15 paperback), which tells two stories: one of Tom, a widowed pastor, who abandons his Japanese wife, Mitsuko, and white son after the attack on Pearl Harbor; the other of Bill, the now-grown son who cannot remember his life in the Japanese-American internment camps in World War II, but feels compelled to locate the Japanese woman he remembers being his mother.

With The Sun Gods, you've gone from being a translator to being a novelist. What was that transition like?

I have been interested in literature, of course, as my subject matter. Then as a translator, I do a lot of writing. I teach translation, and the best advice I have for students who want to be translators is very boring for them, but it's key to the whole process, and that's practice. Writing is like a musical instrument. You have to play a lot. Only when you practice writing can you begin to say what you want to say. So I have a lot of practice translating other people's writing, and my writing has been improving at the same time. It was, I think, a natural progression.

The Sun Gods deals with the American internment camps during World War II. What drew you to this subject?

The Sun Gods deals with the American internment camps during World War II. What drew you to this subject?

Years ago, I started to read about censorship in Japanese. The more I read about censorship in Japanese literature and what system the writers were working under, I got angry, and that sort of gets me going. That's what happened with The Sun Gods: something got me going.

There's a scene in the book where Bill, one of the main characters, meets a person who says, "Well, you know about the camps?" and Bill doesn't know anything about the camps. He's a senior in college and he's never heard that the U.S. government locked up 120,000 people because of the color of their skin and made them stay in these awful camps in the middle of the desert for three to four years. In a way, that's the most autobiographical moment in the book, because I didn't know about any of that stuff until I was in graduate school--that would have been around 1964.

My professor, who was a specialist in Japanese literature, said something to me about these camps, and he told me that this had happened. I felt like saying, "No way! My country doesn't lock people up in concentration camps!" And that's how the character reacts. He just doesn't know a thing about it. That's when I started reading about the internment camps. I did a lot of reading and got all worked up about it. I tend to respond to matters of injustice.

I was struck by the strong sense of place and landscape that pervade the story. How has living in the Pacific Northwest influenced you as a writer, specifically as it relates to this book?

Living here, you're immersed in the history. I moved to the Seattle area in 1975 and that's when what's called the Day of Remembrance was just starting. It happens every year. People who were sent off to the camps get together to talk about their experiences. My wife and I went to one of those days when we first came here. The history of the camps is a much more alive thing here. In the East Coast or Chicago, you can learn about it, but you don't really have a sense in the community that this was something that was suffered by the community and by people you actually know.

That was definitely a push from the surroundings. I also learned that the University of Washington had a special collection on the internment camps, which fueled my interest. At some point, and I don't know when it happened, I went from interested to wanting to write a novel.

Something clicked with the religious angle, too. It was just so amazing to me that people had behaved so badly toward this one racial group while considering themselves children of God, and the hypocrisy of the whole thing made me really upset.

How did you approach your story? Did you have characters in mind already?

My wife and I visited the Japanese Baptist Church here and became aware that they had a white minister at that time. There were all sorts of photographs out front of the Reverend Emery Andrews and his flock, and that struck a chord with me. He ministered to Japanese Americans sent to these camps. It was a moment of thinking about this beloved figure--and it turns out he was an amazing man who moved his family to Twin Falls, Idaho, to be close to Minadoka camp to continue preaching to his congregation; he was a totally devoted Christian in the best sense--somehow that sparked the thought of "what if he was not so great?" and that's where Tom came from. He was the non-Emery Andrews.

When we think about characters, he must have been the first one: a minister who was not faithful to his congregation and ended up betraying them. The whole story started to coalesce around that character.

Writers invariably say that at some point in the novel the characters took on a life of their own and behaved in ways they never expected. I took these kinds of statements with a grain of salt until I wrote my own novel. It was astounding. I still remember the day when Mitsuko did something that was a tremendous indication of her strength. I wrote this scene and it took me totally by surprise. I never imagined she was going to do that. I remember saying over and over again, "What a woman! What a woman!" And she is this total figment of my imagination, but I was so impressed with her! It's this crazy kind of thing. It was the first time I had experienced that, this thing you hear from writers.

What's your relationship with your characters now that your book is done? How do you feel about them? Are they still dwelling in your mind?

Mitsuko is definitely the one that has been my revelation. I don't think I could have dreamed when I started out that I could create a character like that.

How long did it take to write this book?

I started writing The Sun Gods 30 years ago, in 1985. The book was really together in 1987 or '88. My wife and I tried to show it to agents and publishers, but then I got busy translating Murakami and I forgot. Every five or so years my wife and I would remember this book existed and we'd talk about trying to get it published in time for the war's anniversary. This time, when that conversation came up, we both realized we're not going to live much longer, so we decided to try to get this story out for the 70th anniversary. These anniversaries get people focused, and that's certainly what happened to us. Luckily, Chin Music Press was interested. The book has been heavily edited these past few months, so it's finally ready to go out in the world. --Justus Joseph, bookseller at Elliott Bay Book Company

Jay Rubin: From Translator to Novelist

Tad and Dad by David Ezra Stein zeroes in on a tadpole who refuses to leave Dad's side--even at bedtime--which gets more complicated as Tad gets bigger.

Tad and Dad by David Ezra Stein zeroes in on a tadpole who refuses to leave Dad's side--even at bedtime--which gets more complicated as Tad gets bigger.

The Sun Gods deals with the American internment camps during World War II. What drew you to this subject?

The Sun Gods deals with the American internment camps during World War II. What drew you to this subject? Published in 1989, Katherine Dunn's Geek Love (paperback, Vintage) is the story of the Binewskis, a family of itinerant carnival owners. Al and Lil Binewski, the heads of the family, get the idea to integrate their business vertically and through a regime of illegal drugs, poisons and radiation, breed their own sideshow. There is Arturo, the ruthless, megalomaniacal "Aqua Boy"; the beautiful, talented conjoined twins Elly and Iphy; Oly, the hunchback, albino dwarf and the book's narrator; and Chick, the kind-hearted, outwardly normal boy who possesses the most powerful gift of them all. The novel jumps between two time periods: in the first, Oly recalls her childhood and the rise and fall of the Binewski clan; in the second, a much older Oly works to protect what little family she has left. Geek Love is not for the faint of heart. It is a dark, frequently disturbing book. But readers who can stomach the darkness will find a cast of unique characters, splashes of dark humor, and surprising moments of tenderness and warmth, all told through Dunn's incredible prose. --

Published in 1989, Katherine Dunn's Geek Love (paperback, Vintage) is the story of the Binewskis, a family of itinerant carnival owners. Al and Lil Binewski, the heads of the family, get the idea to integrate their business vertically and through a regime of illegal drugs, poisons and radiation, breed their own sideshow. There is Arturo, the ruthless, megalomaniacal "Aqua Boy"; the beautiful, talented conjoined twins Elly and Iphy; Oly, the hunchback, albino dwarf and the book's narrator; and Chick, the kind-hearted, outwardly normal boy who possesses the most powerful gift of them all. The novel jumps between two time periods: in the first, Oly recalls her childhood and the rise and fall of the Binewski clan; in the second, a much older Oly works to protect what little family she has left. Geek Love is not for the faint of heart. It is a dark, frequently disturbing book. But readers who can stomach the darkness will find a cast of unique characters, splashes of dark humor, and surprising moments of tenderness and warmth, all told through Dunn's incredible prose. --