_Jonny_Donovan_(Small).jpg) |

| photo: Jonny Donovan |

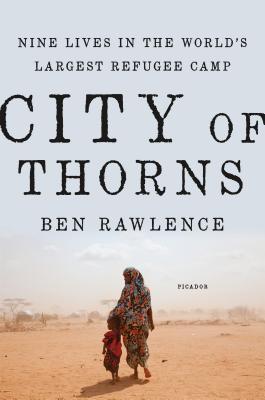

Ben Rawlence studied Swahili and history at the University of London and received a Master's Degree in International Relations from the University of Chicago. He has written for the Guardian, the London Review of Books, the Huffington Post, Prospect and the New Yorker. Rawlence worked as speechwriter for the U.K.'s Liberal Democrats before joining Human Rights Watch, an international non-governmental organization that advocates for human rights. Radio Congo, his first book, chronicled the lives of individuals during and after the Congo war. City of Thorns: Nine Lives in the World's Largest Refugee Camp (reviewed below) is a first-hand account of nine refugees in a camp in Kenya called Dadaab whom Rawlence observed over the course of four years while working as a researcher for Human Rights Watch.

In the prologue to City of Thorns, you write about an October 2014 meeting at the White House in which you briefed the National Security Council about the situation in Dadaab, but their focus was on the radicalization of Somalian youth. Has concern for the well-being of African refugees continued to be secondary?

I think the discussion that I described is a microcosm of the issues that are being discussed in North America and Europe right now. In some countries compassion is winning out--as in Canada and Germany. Unfortunately, in many others the reverse is true.

Celebrity intervention and human rights groups, except for brief periods, have not been able to shift the focus from terrorism.

I think we need more stories, different stories; whole, rounded stories that do not present lives as simply examples or tokens of arguments. That is what I have tried to do in this book. The solidarity in many countries with refugees despite a lot of official cynicism shows that many people can and do still think for themselves.

There seems to be a disconnect in how men and women view the camps--the hype and "allure" of the camp becomes a point of contention in the relationships of several of the people you covered: Guled and Maryam, Nisho and Billai, Monday and Muna. Why do the men feel the need create the illusion that the camp is better than it really is?

I think for each person it is different. They assemble the facts of their lives into narratives that make sense to them. For Guled, he is genuinely at risk, so he has to believe in the camp. For Nisho, it is about independence, and also fear of the unknown. For Monday, the camp is the route to a better life that he still hopes for, even if Muna has given up.

In your experience as a human rights watcher, how does the situation in Dadaab compare to the current situation in Syria?

In your experience as a human rights watcher, how does the situation in Dadaab compare to the current situation in Syria?

Life in a refugee camp and life in a war zone have many similarities and many differences, but the active threat to life is absent in the camp. The main difference in the Somali refugee experience is how protracted it has become. Dadaab is 25 years old. People went to the camps expecting to be there for a short time, either to go home or to another country. Syrians seem to be much more reluctant to remain in camps. Partly that is because the illegal route to Europe is cheaper and shorter than from Somalia, but also I think the Syrians are recognising that the international refugee quota system is broken and acting accordingly.

In light of the recent terrorist attacks in San Bernardino and Paris and talk in the U.S. of not accepting Syrian refugees because of terrorist fears, how will this affect the Dadaab refugees' chances of repatriating abroad?

I am sure it will make it more difficult; indeed, the international climate has already led to massive reductions in national quotas for Somali refugees

It would seem that former youth leader Tawane would have been at the top of the list for repatriation given his work as an intermediary between the NGOs and the citizens of the camp, yet even he was unable to escape the bureaucratic red tape except to go back into Somalia and begin his own NGO. Have you kept in touch with Tawane?

I have, and he is doing well. He is still in the camp but running his NGO from there.

Do you think Tawane will ever leave Dadaab?

I really don't know, and I think he doesn't know either. What I tried to do in the camp is to convey the sense of the mind of people trapped in the camp--and the way the world appears from that vantage point is difficult and scary. Every move seems both necessary and impossible at the same time. And because of each person's history, the changing political landscape (the war and the politics surrounding return) resonates in different ways at different times. Being in limbo is a very inconsistent place for someone to be--it is hard to imagine the future when you have never known stability, and at the same time, you must imagine a future in order to survive.

What do you think could be done to bring more Western attention to the situation in Dadaab? And do you see any resolution to the crisis in the Horn of Africa?

I think the West--that is, Western governments--understand well the hardships of life in Dadaab but they have no ideas, no money and most of all no real will to solve the crisis of the camp. The generosity towards Syria was forced on rich governments by the sheer numbers arriving in Europe; that is unlikely to happen with Somalia. Somalis, Ethiopians and Eritreans have been arriving on European shores for more than a decade, and the numbers show no signs of slowing. The crisis in the Horn of Africa is unlikely to end any time soon; like the Middle East, it is rooted in unrealistic colonial borders and sustained by regional geopolitics and bad government. --Nancy Powell, freelance writer and technical consultant

Ben Rawlence: Telling the Stories of Refugees in the Horn of Africa

Marlon James, whose most recent novel, A Brief History of Seven Killings (Riverhead), won the 2015 Man Booker Prize. He teaches at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn., where Gov. Mark Dayton declared Marlon James Day in October.

Marlon James, whose most recent novel, A Brief History of Seven Killings (Riverhead), won the 2015 Man Booker Prize. He teaches at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minn., where Gov. Mark Dayton declared Marlon James Day in October. Mary-Louise Parker is a Tony, Emmy and Golden Globe Award-winning actress. Dear Mr. You (Scribner) is her first book.

Mary-Louise Parker is a Tony, Emmy and Golden Globe Award-winning actress. Dear Mr. You (Scribner) is her first book.

_Jonny_Donovan_(Small).jpg)

In your experience as a human rights watcher, how does the situation in Dadaab compare to the current situation in Syria?

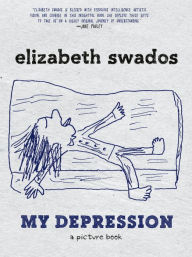

In your experience as a human rights watcher, how does the situation in Dadaab compare to the current situation in Syria?  Swados was also an author whose work spanned many genres: she wrote three novels, seven books for children and two memoirs. The Four of Us: The Story of a Family was about her difficult family life (her mother suffered from depression and alcoholism and committed suicide; her brother became schizophrenic and also committed suicide). Her best-known book is her other memoir, My Depression: A Picture Book, which first was published in 2005 and came out in a new paperback edition last year from Seven Story Press. In the book, Swados chronicles her battles with depression, made all the more harrowing by her family history. She adapted the book into an animated film called My Depression (The Up and Down and Up of It), starring Sigourney Weaver and Fred Armisen, that made its debut on HBO last July.

Swados was also an author whose work spanned many genres: she wrote three novels, seven books for children and two memoirs. The Four of Us: The Story of a Family was about her difficult family life (her mother suffered from depression and alcoholism and committed suicide; her brother became schizophrenic and also committed suicide). Her best-known book is her other memoir, My Depression: A Picture Book, which first was published in 2005 and came out in a new paperback edition last year from Seven Story Press. In the book, Swados chronicles her battles with depression, made all the more harrowing by her family history. She adapted the book into an animated film called My Depression (The Up and Down and Up of It), starring Sigourney Weaver and Fred Armisen, that made its debut on HBO last July.