|

| photo: Sameer A. Khan |

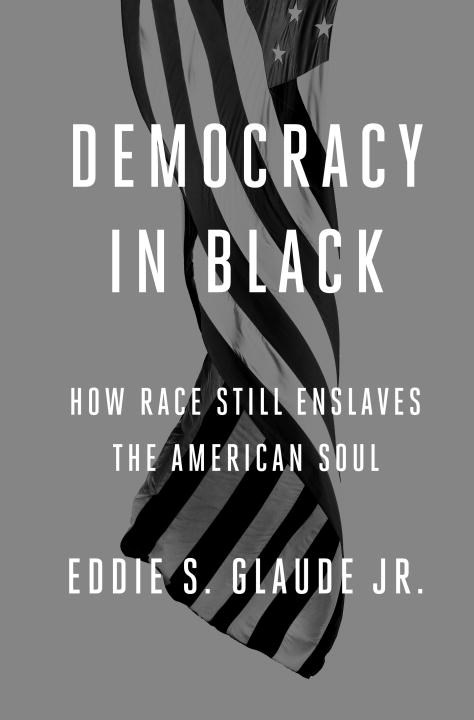

Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. is chair of the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University and the William S. Tod Professor of Religion and African American Studies. He is the author of Exodus! Religion, Race and Nation in Early 19th Century Black America and In a Shade of Blue: Pragmatism and the Politics of Black America. His newest book, Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul (see our review below), presents provocative arguments about the state of black America and what must be done to achieve true equality.

Democracy in Black is being published at a time of striking racial ferment in the United States. Do you ever fear that the pace of events will overtake your book? Did you have any desire to incorporate--for example--the ongoing wave of campus protests into Democracy in Black?

While I was writing the book, I worried that the events of the day would overwhelm the argument. Things were happening so fast that my examples felt dated almost as soon as I wrote about them. But I decided to write a book that would help frame the pace of events--help us see them as critical interventions in a broader effort to reimagine American democracy. The protests, however varied and fluid, represent a key dimension of my call for "a revolution of value"--that we need a fundamental change in how we view government, how we view black people, and how we view what matters. So I didn't try to revise the book with news of every new death at the hands of the police or with every new protest. I needed to write something to help people see and interpret what was happening right in front of them at breathtaking speed.

One of the most dramatic campus protest movements has been taking place at Princeton University, where you teach. What would you say to students, faculty or members of the general public who oppose the Black Justice League's attempts to remove Woodrow Wilson's name and likeness from Princeton's campus?

I am so proud of our students. They have taken the energy of Black Lives Matter and brought it to our campus, forcing the administration and the broader Princeton community to grapple with the story we tell ourselves about Woodrow Wilson and face the disturbing fact that, for many of our students, Princeton isn't the most welcoming space. Without their protests, it would be business as usual here. And black students would simply have to endure in silence. Now not only is Princeton struggling with Wilson's racism, but the nation is as well. And that is a good thing.

Whether you agree with the demands or not, the students have opened up space for a reimagining of Princeton University. I like to say that President Wilson has defined what Princeton has been; we now have a chance to define what Princeton will be. This mirrors what is happening all around the country. The protests have opened up space for us to reimagine American democracy--to glimpse what this country could be apart from those who say that our only choices are what is currently right in front of us. And that use of the imagination, to my mind, is a revolutionary act.

In Democracy in Black, you point repeatedly to the "collapse of black institutional life" as a key factor in the "current crisis in black America." How do you answer critics who insist that the decline of black churches, traditionally black colleges, and other "safe and creative spaces to combat racism" is a result of successful integration?

In Democracy in Black, you point repeatedly to the "collapse of black institutional life" as a key factor in the "current crisis in black America." How do you answer critics who insist that the decline of black churches, traditionally black colleges, and other "safe and creative spaces to combat racism" is a result of successful integration?

Well, I would challenge the assumption--that is, I don't believe we have experienced successful integration in too many domains of American life. We can think about all of the black teachers, principals and superintendents who lost their jobs after the so-called integration of schools. And we know that American education is as segregated today as it was in the 1960s. My point is not so much about a nostalgic longing for black institutions. It is really to understand the importance of these institutions in a society fundamentally shaped by the value gap (the belief that white people are valued more than others). What happens when those institutions collapse and we still live in a society in which black people are valued less? They (we) are even more vulnerable. So I would challenge the assumption. We haven't achieved genuine integration in this country. If anyone tells you otherwise, I have a bridge in Brooklyn I want to sell you.

One of the main theses of Democracy in Black seems to be that black liberalism has become intellectually bankrupt while simultaneously maintaining, as you say, a stranglehold on the black community's political imagination. You also decry black leaders, such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, who play the "racial advocacy game." Do you fear alienating older black liberals who see themselves as having fought tooth and nail for gains that you now describe as, at best, limited?

They have fought tooth and nail. I don't want to deny that. And I don't want to seem disrespectful, because I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for their sacrifice and struggle. But we have to be honest in our current assessment. A particular approach to black politics, one indebted to a certain understanding of Dr. King, has reigned supreme for the last 30 years. And over those 30 years we, especially the black middle class, have experienced some advances. But today, by every statistical measure, Black America is suffering. And it has been on their watch. We can't deny that.

I believe we have to change the way we do black politics. One strand of argument in the book is that black democratic participation is distorted and disfigured. We have a model of black leadership that often asks black folk to outsource the work of democracy to purported leaders who represent them to the powers that be. Sort of like an emphasis on preachers in the pulpit instead of the folks in the pews. The protests in the street represent not only a challenge to the state, but a direct challenge to this model of leadership--especially in its emphasis on the most marginal within black communities (e.g., LGBT, transgender, etc.) that often go unaddressed in traditional circles.

You dedicated Democracy in Black in part to Cornel West, who posted a takedown of National Book Award-winner Ta-Nehisi Coates on Facebook. Do you have any thoughts about Coates or the remarkable success of his book, Between the World and Me?

I find the success of the book interesting and, in some ways, an occasion for analysis.

What's fascinating is the argument, right? That some believe he has offered a definitive account of our current malaise. White supremacy comes off as something fixed and unchangeable, something like oxygen, and his answer to that--even when his son is crying after the non-verdict of Darren Wilson--is simply to commend constant interrogation and struggle. To my mind, struggling and questioning alone are not enough. Two-year-olds do that. We have to ask why we struggle and why we question. What is required is a broader vision of democracy, a view of the world in which we stand in right relation to one another. That involves, as the historian Robin D.G. Kelley noted, "freedom dreams."

But, in Coates's hands, our political imaginations are confined to the realities and constraints of white supremacy. He refuses to imagine seeing beyond it. Anything else amounts to facile utopianism or a failure of nerve to look the facts of our experience squarely in the face. This is not only wrong in its details; it is profoundly dangerous.

I don't think you can hide behind a claim that the book is art (literature) to avoid the political implications of your argument. The book has politics, and we need to be clear what they are. So, I actually think the book is wildly popular because the argument resigns us to the current state of things. That might not be a generous read, but that is how I feel.

Now, don't get me wrong. Democracy in Black begins in a similar place: we have to look the ugliness of the value gap and our racial habits squarely in the face, and we must, without hesitation, free ourselves from the illusion that this country is God's gift to the earth. That belief blinds us to the suffering in our midst. In this, I am in complete agreement with Coates.

But I stand in the tradition of James Baldwin. Baldwin's spirit animates the entire argument of Democracy in Black. For him, white supremacy distorts and disfigures us. And we, black folk, have to work hard to keep it from permanently damaging our souls. But that is not all. He doesn't commend that we stay in a holding pattern in light of the permanency of white supremacy--that we just "make do" as we say back home in Mississippi. Instead, Baldwin urged us, and by extension the nation, to reimagine who we take ourselves to be--to step outside of the cage of stereotypes and our various idols that bind us and create a new world. No matter the circumstances, we had to do this work, he insisted, because in the end it was our responsibility to raise our babies to be bolder and daring, not to resign themselves to a "world of plunder" and live in fear.

When you look to the future of black America, do you feel more hope or dread?

There is a powerful line in W.E.B. DuBois's classic book, The Souls of Black Folk, in the chapter about the death of his son. DuBois writes of "a hope not hopeless but unhopeful." It is a blues-soaked sensibility that orients one to a world in which folks, as Toni Morrison wrote in Beloved, can "dirty you so bad on the inside that you couldn't like yourself anymore." I feel hope, but it is drenched in loss and brokenness. So I am not naïve. My hope is in us. Together, the few of us willing to turn our backs on the order of things can change the world--or we can watch it go to hell. It's in our hands. I have to believe that. Otherwise it would be too easy to just take the bribe and live a comfortable life amid the ruins--to become a monster of a sort.

I see people in the streets making folk uncomfortable, demanding that we reject the status quo and reimagine ourselves. They are saying no to the way this country is organized; they are doing democracy in black. That is, they are fighting for democracy shorn of the value gap. It is a tall order. Forces of bigotry and greed are powerful, and defeat more than likely awaits. We fight nevertheless for a better world for our children and our children's children. We step outside of the script written for us, and that act has revolutionary potential. That's where my hope resides. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books

Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.: Where Hope Resides

In Democracy in Black, you point repeatedly to the "collapse of black institutional life" as a key factor in the "current crisis in black America." How do you answer critics who insist that the decline of black churches, traditionally black colleges, and other "safe and creative spaces to combat racism" is a result of successful integration?

In Democracy in Black, you point repeatedly to the "collapse of black institutional life" as a key factor in the "current crisis in black America." How do you answer critics who insist that the decline of black churches, traditionally black colleges, and other "safe and creative spaces to combat racism" is a result of successful integration? Rarely has a single book caused as much social and political change as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Published by Houghton Mifflin in 1962 after a serialized run in the New Yorker, the book documented how reckless pesticide use was damaging the environment and decimating bird populations. Chemical companies unleashed a barrage of disinformation against Carson and the other scientists who supported her claims, but the public was already decisively swayed. Silent Spring is credited with inspiring the modern environmentalism movement and President Nixon's creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. Pesticide use is now highly regulated in the United States and DDT spraying is restricted by global treaties.

Rarely has a single book caused as much social and political change as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Published by Houghton Mifflin in 1962 after a serialized run in the New Yorker, the book documented how reckless pesticide use was damaging the environment and decimating bird populations. Chemical companies unleashed a barrage of disinformation against Carson and the other scientists who supported her claims, but the public was already decisively swayed. Silent Spring is credited with inspiring the modern environmentalism movement and President Nixon's creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. Pesticide use is now highly regulated in the United States and DDT spraying is restricted by global treaties.