.jpg) |

| Photo: Anna Wu Photography |

Shawna Yang Ryan, former Fulbright scholar and author of The Water Ghosts, teaches creative writing at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa. Her newest book is Green Island (reviewed below), a historical novel depicting multiple generations of a family struggling to survive in Taiwan and, later, in the United States, during a period of martial law and political oppression lasting from 1949 to 1987--the White Terror. Our review is below.

Green Island feels like a very personal book. How much of a role did your family history or your time as a Fulbright scholar in Taiwan play in the book's inception? Did your mother ever tell stories about the White Terror?

The relationship of my family history to the story told in the book is complicated. When I began the project, my understanding of Taiwan's history was so thin that I didn't understand these dynamics. My grandparents came to Taiwan from China in 1949 with the Kuomintang (KMT). My mother and five of her seven siblings were born and raised in Taiwan. In my book, the relationship between the arriving Chinese and the Taiwanese is very fraught, but I didn't want to make the Chinese one-dimensional enemies because I saw firsthand how traumatic that migration had been for my own family (and that's also just bad writing!). The Chinese who arrived were not exempt from the KMT policies or the effects of the White Terror. Saying this, I'm not trying to diminish the terrible things that the KMT did to the people of Taiwan. But in novels, one must attend to the nuances of a situation.

My mom told me very few stories, but the effects of living under martial law emerged in other ways, in a kind of reflexive secretiveness that I didn't understand until I had started this book. So I wanted to tell this story because there was so much silence around it.

Readers might assume that the title of your book, Green Island, refers to the verdant island of Taiwan, but, in fact, it refers to a small island off the coast of Taiwan where political prisoners were held during the White Terror. Have you ever been to Green Island?

I've been to Green Island twice--once, 10 years ago, and then last summer I revisited it and the prison. I named the book after it for the exact reason you state--it works on multiple levels. It's both literal and a metaphor. Green Island the prison and Taiwan, a lush, green island, as a kind of prison during martial law. Also, as the epigraph indicates, there's a beautiful song about Green Island, "Green Island Serenade," that expresses the yearning that is a pervasive tone of the book.

In writing Green Island, did you reflect on the discrepancy between Taiwan's surface beauty and the painful history of the island?

It is a kind of irony, but a kind of irony that is not exclusive to Taiwan. For example, I'm currently living in Hawaiʻi, where there is also a discrepancy between the physical beauty and a painful history. Could it be that very beauty that draws so many people to a place and leads to the difficult and sometimes violent contestations of ownership?

Events such as the White Terror or the 2-28 Massacre remain virtually unknown in the United States, despite the country's key role in Taiwanese history--the U.S. helped to establish and prop up the repressive KMT regime. Did you want in part to raise awareness of forgotten tragedies and of U.S. complicity in them?

Definitely. When I started this in my mid-20s, I was a bit naïve about how governments work, and researching this opened my eyes, particularly to America's role in supporting a repressive regime for their own self-interest. The story began to take shape as I thought about this. I thought that if Americans just knew Taiwan's story, they might think differently about our current policies toward it--and perhaps toward other places as well.

How did you navigate the hybrid culture that emerged in Taiwan thanks to successive occupations by the Japanese and mainland Chinese as well as exposure to American servicemen living on military bases? Do you think this mélange of influences has made it difficult to establish a national identity for Taiwanese citizens or descendants?

The research was challenging because once I had done my homework on Taiwan, I had to attend to my weak understanding of Japanese history and culture. I actually got quite into it, and in another draft of the book, I had parts that took place in Japan and delved more into the lingering effects of the Japanese colonial era, such as the largely unacknowledged use of Taiwanese women as sex slaves and the controversial enshrinement of indigenous Taiwanese in the Yasukuni Shrine.

As far as the period when American servicemen were stationed in Taiwan, I found a number of really cool and useful blogs run by former servicemen with pictures and reminiscences.

I don't think this cultural melange has made it difficult to establish a national identity--rather, I think it's the heart of Taiwan's national identity, and what distinguishes it from its neighbors.

Green Island becomes an immigrant story when the protagonist marries a Taiwanese professor and moves with him to Berkeley, Calif., in the early 1980s. As a native of California, how did you put yourself in the mindset of someone struggling to integrate into American culture?

Green Island becomes an immigrant story when the protagonist marries a Taiwanese professor and moves with him to Berkeley, Calif., in the early 1980s. As a native of California, how did you put yourself in the mindset of someone struggling to integrate into American culture?

I witnessed it with my own mother, and then as our various relatives immigrated and lived with us. My mother had been in the U.S. for only a few years when I was born, so by the time I started to have conscious memories, she was still in the process of adapting. And then when I got older, I saw my aunts and uncles experience it. I always had a sense of being both inside and outside of the mainstream lingering at the edge of my consciousness, and it wasn't until I went to college and started learning about identity formation that I could identify and name that feeling. I've thought a lot about the inheritance of experience, and how the impact of these events gets passed on subconsciously; this is one of those situations where I felt my mother working through this experience in a way that was so pervasive to my childhood, so suffused into our lives, that I couldn't see it until I was an adult.

Your novel has the corrosive moral force of repressive governments as one of its main themes. Green Island's characters are often ordinary people coerced into collaboration or silence. Was it difficult to write a protagonist who remains somewhat passive in the face of repression? Is there a part of Taiwanese culture, Asian culture or just human nature that makes obedience "easier than defiance?"

I don't think it's particular to a culture. It's human nature. It's easier to take care of immediate comfort and self-interest than to fight for abstract ideals that may put you in danger. I wanted the character's passivity to pose ethical questions for the reader. What would they do in her place? Is she morally reprehensible or merely doing the best that she's able?

She would have been a lot less interesting if she had made all the right choices!

Why is your protagonist never given a name?

For a while, I toyed with the title Nameless for the book. I liked the sound, and also the implication, since there's so much controversy over what Taiwan is called. Taiwan? The Republic of China? Chinese Taipei?

In the beginning, I wanted to see how far into the story I could go without giving the narrator a name, as a sort of challenge. After she had been nameless for so long, I couldn't think of a name that would fit her, so I decided to leave her without one.

You write that "In our world, love was supposed to be unspoken and understood." Is it difficult to write characters who frown on expressing emotion? Or does it just make the interior life of those characters that much more interesting?

I think of how powerful it is to see in movies a character under-react when you expect wailing. The suppression of emotion seems that much more poignant. Sometimes effusive, flamboyant emotion can alienate a viewer/reader from a character. In the book, Baba [the protagonist's father] is so reticent, yet he's clearly a man of deep passions, and those passions get channeled through other actions that are detrimental to himself and his family. It gave me an opportunity to complicate the story even more. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books

Shawna Yang Ryan: Green Island Serenade

"The crowd quieted as lone Mustafa came onstage, striking a beat hard and sharp with his hickory sticks. He carried the beat to his drum kit and another spotlight came on as he set into a blues shuffle... Goldie blew a first skronky peal from the sax and all the stage lit up.... Young Mustafa's eyes watched Bailey with a reverential focus, barely suppressing his joy, doing better than best to push the band. Dan and Pops built a base with their groove. B-Bird made it full, and when Goldie and Bailey reached out to each other, the band brought both old-time believers and converts to the congregation of 'Everyday I Have the Blues.' "

"The crowd quieted as lone Mustafa came onstage, striking a beat hard and sharp with his hickory sticks. He carried the beat to his drum kit and another spotlight came on as he set into a blues shuffle... Goldie blew a first skronky peal from the sax and all the stage lit up.... Young Mustafa's eyes watched Bailey with a reverential focus, barely suppressing his joy, doing better than best to push the band. Dan and Pops built a base with their groove. B-Bird made it full, and when Goldie and Bailey reached out to each other, the band brought both old-time believers and converts to the congregation of 'Everyday I Have the Blues.' "

.jpg)

Green Island becomes an immigrant story when the protagonist marries a Taiwanese professor and moves with him to Berkeley, Calif., in the early 1980s. As a native of California, how did you put yourself in the mindset of someone struggling to integrate into American culture?

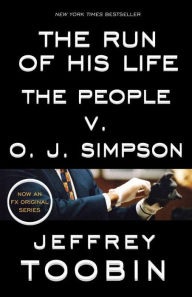

Green Island becomes an immigrant story when the protagonist marries a Taiwanese professor and moves with him to Berkeley, Calif., in the early 1980s. As a native of California, how did you put yourself in the mindset of someone struggling to integrate into American culture? The white Bronco, the black glove, a simmering city ready to boil over into another race riot: these familiar images are back on American televisions thanks to FX's American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, a dramatization of the 1994-95 arrest and trial of O.J. Simpson for the murders of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman. Thus far, five of nine episodes have aired to resounding critical acclaim and solid ratings, with special accolades for strong performances from Sarah Paulson as prosecutor Marcia Clark and Courtney B. Vance as Johnnie Cochran; other cast members include Cuba Gooding, Jr. as O.J. Simpson, Nathan Lane as F. Lee Bailey, David Schwimmer as Robert Kardashian and John Travolta as a creepy Robert Shapiro. It airs Tuesdays at 10 p.m.

The white Bronco, the black glove, a simmering city ready to boil over into another race riot: these familiar images are back on American televisions thanks to FX's American Crime Story: The People v. O.J. Simpson, a dramatization of the 1994-95 arrest and trial of O.J. Simpson for the murders of Nicole Brown and Ronald Goldman. Thus far, five of nine episodes have aired to resounding critical acclaim and solid ratings, with special accolades for strong performances from Sarah Paulson as prosecutor Marcia Clark and Courtney B. Vance as Johnnie Cochran; other cast members include Cuba Gooding, Jr. as O.J. Simpson, Nathan Lane as F. Lee Bailey, David Schwimmer as Robert Kardashian and John Travolta as a creepy Robert Shapiro. It airs Tuesdays at 10 p.m.