|

| photo: Sarah Shatz |

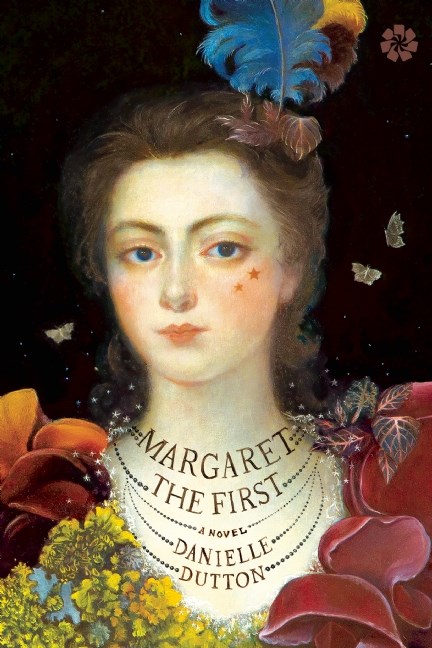

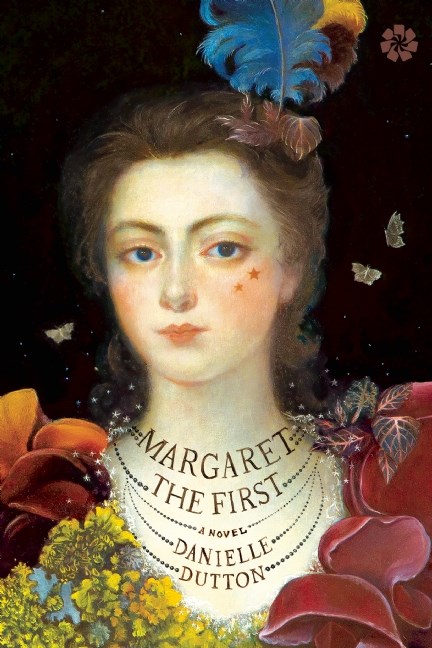

Danielle Dutton is the author of the prose collection Attempts at Life and the experimental novel S P R A W L. In 2010, she founded the small press Dorothy, which publishes works "mostly by women" and was described by Flavorwire as "slyly changing the industry for the better." Dutton's latest novel, Margaret the First (Catapult, March 15, 2016), pays homage to Margaret Cavendish, a 17th-century English duchess who broke from convention by writing poems, plays and philosophy and being the first woman to attend a meeting at the Royal Society of London.

What sparked your interest in Margaret Cavendish?

I first read about her in Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, in this very colorful description of the "hare-brained, fantastical" Margaret Cavendish. Woolf isn't overly kind to Margaret, though you get the sense she wishes she could be. She writes: "[Cavendish] should have had a microscope put in her hand. She should have been taught to look at the stars and reason scientifically." I first read A Room when I was about 24; it had a big impact on me, but I didn't really home in on Margaret until I re-encountered her a few years later, in a course I took in graduate school on the science and literature of the 17th century. This time, I was totally struck by her, and the more I learned, the more wonderful she seemed: "fantastical," yes, but "hare-brained," not so much.

How did you tackle the historical research--on a regimented schedule or whenever inspiration struck?

Much more inspiration than regimen! Maybe I should preface this by saying that I was a history major in college, specifically focused on British history, and lived in England for a year after. So there was a certain amount of grounding I went in with. Beyond that, I went wherever my fascinations led me. I read books about Margaret, of course, and about other figures of the era, but I also read books on 17th-century garden design, and recipes and medical treatments (often there wasn't much difference between a recipe and a medical treatment), and about the scientific experiments and instruments of the age, which themselves could be quite fantastical. As a writer I tend to be driven by wonder, and I just sort of filled myself up on all of this.

Margaret saw an explosion in publishing during her lifetime (she talks of "new scores of pamphlets being printed each day"). It makes me think of how digital media has proliferated knowledge in a similarly novel way. Are there cultural similarities between that time and now?

Margaret saw an explosion in publishing during her lifetime (she talks of "new scores of pamphlets being printed each day"). It makes me think of how digital media has proliferated knowledge in a similarly novel way. Are there cultural similarities between that time and now?

In some ways, Margaret's time is the beginning of now. This was the start of the Enlightenment, and of science and technology as we think of it. The generative sloppiness of the Renaissance was giving way to all-things-empirical, and Margaret, with her ambition and strangeness, had a foot in each world. She was arguably the first tabloid celebrity--as the original "daily papers" printed gossip about her. But she also had very serious aspirations, and was the first woman invited to the Royal Society, the fountainhead of modern science.

You've mentioned that you began writing this novel 10 years ago. I imagine that in that amount of time, a character becomes intimately woven into your thoughts. Has Margaret affected how you see the world or yourself in a way that will persist even now that the book is finished?

Yes, sure. Of course, the Margaret who landed on the page has plenty of pieces of me in her, but in writing her I'm sure I internalized pieces of her as well. One thing I think a lot about in this moment, just as Margaret the First is officially making its way out into the world, is how nervous and ambitious Margaret herself felt for each of her books upon their publication. But she was also so bold, so sure that she should be read. So I do think about her, about her ambition, and remind myself that it is natural to want your book to be read.

Was it ever a struggle to imagine how Margaret might have felt about a given event or situation, particularly those that were deeply personal (e.g., her challenges with childbirth or her relationship with her husband)? How did you approach that?

Absolutely. I thought a lot about how a person in the 17th century would conceptualize "the self," for example. I was always trying to be as historically accurate as I could, but I was also dealing with a lot of psychology, with thoughts and feelings, the stuff not found in the history books. Ultimately my allegiance was to the artistic needs of the book I was writing, the story I was telling, which often meant having to imagine my way into what Margaret might have thought.

In the 17th century, it was highly unusual to come across women who wrote books. Today, it's common, and yet it's been argued that male authors still receive more attention and review in major publications. Do you think women still face greater barriers to being taken seriously as artists?

Even without things like the VIDA numbers to demonstrate that this is the case, I would know it to be true based on my own experiences as a woman and on the stories and experiences of so many other women. Women have a harder time being taken seriously as human beings, much less as artists. There's an example I return to in my mind, because I found it so insidious and illustrative: I once heard a very intelligent and extremely well-read man say that he liked a particular book he was reading because he couldn't tell from the writing that it was written by a woman. Too bad I didn't have a copy of A Room of One's Own in my bag to toss in his general direction.

Margaret's husband, William, was supportive of her trailblazing and was progressive in his own way. At one point, his own plays were even mistakenly credited to her. How unusual was it for a man of his time to support his wife in becoming a public intellectual?

Very, very unusual! It's hard to imagine her career without him, but even more extraordinary, to me, was how unconditionally loving he was, and how (mostly) uncondescending. That warmth and respect became a crucial thing in the book (and no doubt in her life), because otherwise Margaret's world was not all that kind to her. --Annie Atherton

Danielle Dutton: Championing Women Writers, Past and Present

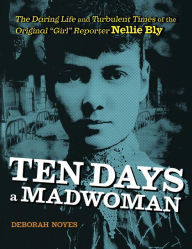

In 1887, 23-year-old "Nellie Bly" (born Elizabeth Cochran) from Pennsylvania moved to New York City to become a journalist. The World hired her to pretend to be insane, so she could be committed to an asylum on Blackwell's Island and report on the horrific conditions from the inside. "How will you get me out?" Nellie asked her editor. "I don't know. Only get in," he said. In Ten Days a Madwoman (Viking)--a truly thrilling, appealingly designed, photo-laden biography by Deborah Noyes (Encyclopedia of the End)--readers will not only get a chilling look into the horrors of Blackwell's Island, but also a sense of women's challenges in 19th-century America. (Ages 10-up)

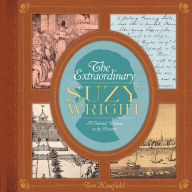

In 1887, 23-year-old "Nellie Bly" (born Elizabeth Cochran) from Pennsylvania moved to New York City to become a journalist. The World hired her to pretend to be insane, so she could be committed to an asylum on Blackwell's Island and report on the horrific conditions from the inside. "How will you get me out?" Nellie asked her editor. "I don't know. Only get in," he said. In Ten Days a Madwoman (Viking)--a truly thrilling, appealingly designed, photo-laden biography by Deborah Noyes (Encyclopedia of the End)--readers will not only get a chilling look into the horrors of Blackwell's Island, but also a sense of women's challenges in 19th-century America. (Ages 10-up) England-born Quaker Susanna Wright (1697-1794) was a frontierswoman in colonial America, a renowned poet and a political activist who worked for Native American rights and was influential at the highest levels of Pennsylvania government. In The Extraordinary Suzy Wright (Abrams)--a handsomely designed, finely crafted biography--Teri Kanefield (The Girl from the Tar Paper School) tells Wright's story--and that of early Pennsylvania--in crystal-clear prose enhanced by period illustrations, letters and contemporary photographs. (Ages 8-12)

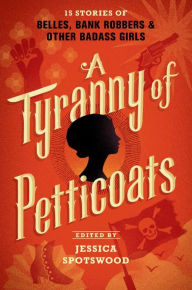

England-born Quaker Susanna Wright (1697-1794) was a frontierswoman in colonial America, a renowned poet and a political activist who worked for Native American rights and was influential at the highest levels of Pennsylvania government. In The Extraordinary Suzy Wright (Abrams)--a handsomely designed, finely crafted biography--Teri Kanefield (The Girl from the Tar Paper School) tells Wright's story--and that of early Pennsylvania--in crystal-clear prose enhanced by period illustrations, letters and contemporary photographs. (Ages 8-12) A Tyranny of Petticoats: 15 Stories of Belles, Bank Robbers & Other Badass Girls (Candlewick) is Jessica Spotswood's (Cahill Witch Chronicles) anthology of new stories about "clever, interesting American girls throughout history." It's a terrific collection written by "an impressive sisterhood" of 15 YA authors, including Andrea Cremer, Marie Lu, Marissa Meyer and Elizabeth Wein. Readers will find themselves entrenched in 1848 Texas (Leslye Walton's "El Destinos") or 1967 California (Kekla Magoon's "Pulse of the Panthers"). As Spotswood writes in her introduction, "They debate marriage proposals, murder, and politics with equal aplomb." (Ages 14-up) --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness

A Tyranny of Petticoats: 15 Stories of Belles, Bank Robbers & Other Badass Girls (Candlewick) is Jessica Spotswood's (Cahill Witch Chronicles) anthology of new stories about "clever, interesting American girls throughout history." It's a terrific collection written by "an impressive sisterhood" of 15 YA authors, including Andrea Cremer, Marie Lu, Marissa Meyer and Elizabeth Wein. Readers will find themselves entrenched in 1848 Texas (Leslye Walton's "El Destinos") or 1967 California (Kekla Magoon's "Pulse of the Panthers"). As Spotswood writes in her introduction, "They debate marriage proposals, murder, and politics with equal aplomb." (Ages 14-up) --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Margaret saw an explosion in publishing during her lifetime (she talks of "new scores of pamphlets being printed each day"). It makes me think of how digital media has proliferated knowledge in a similarly novel way. Are there cultural similarities between that time and now?

Margaret saw an explosion in publishing during her lifetime (she talks of "new scores of pamphlets being printed each day"). It makes me think of how digital media has proliferated knowledge in a similarly novel way. Are there cultural similarities between that time and now? Markus Zusak's The Book Thief is narrated by Death itself, an appropriate guide for the grisly era the book depicts. It follows Liesel Meminger, an illiterate German nine-year-old sent to live with working-class foster parents after her brother dies. The Nazis are in power, and Liesel is exposed to the regime's escalating horrors. She takes solace in learning to read with her foster father, in stealing books the Nazis want to destroy, and in befriending the Jewish man her foster parents hide in the basement. Omniscient Death haunts them all the while.

Markus Zusak's The Book Thief is narrated by Death itself, an appropriate guide for the grisly era the book depicts. It follows Liesel Meminger, an illiterate German nine-year-old sent to live with working-class foster parents after her brother dies. The Nazis are in power, and Liesel is exposed to the regime's escalating horrors. She takes solace in learning to read with her foster father, in stealing books the Nazis want to destroy, and in befriending the Jewish man her foster parents hide in the basement. Omniscient Death haunts them all the while.