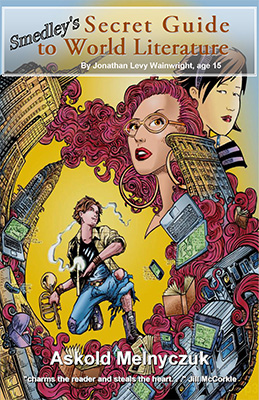

Askold Melnyczuk's latest novel, Smedley's Secret Guide to World Literature (PFP Publishing), has an intriguing subtitle: "By Jonathan Levy Wainwright, age 15." Jill McCorkle praised the young narrator as someone who "immediately charms the reader with his brilliant literary observations and insights, but what really steals the heart is that it comes on a wave of adolescent angst we all recognize--hormones and family problems and pop culture fuel this difficult journey while great and sometimes forgotten literary voices educate and shine light on his young and vulnerable heart." I agreed and had a few questions for the author behind that narrator. Melnyczuk's previous novels include What Is Told, The Ambassador of the Dead and The House of Widows. He was the founding editor of Agni magazine and Arrowsmith Press. An associate professor in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts, Melnyczuk also teaches at the Bennington College Writing Seminars.

Askold Melnyczuk's latest novel, Smedley's Secret Guide to World Literature (PFP Publishing), has an intriguing subtitle: "By Jonathan Levy Wainwright, age 15." Jill McCorkle praised the young narrator as someone who "immediately charms the reader with his brilliant literary observations and insights, but what really steals the heart is that it comes on a wave of adolescent angst we all recognize--hormones and family problems and pop culture fuel this difficult journey while great and sometimes forgotten literary voices educate and shine light on his young and vulnerable heart." I agreed and had a few questions for the author behind that narrator. Melnyczuk's previous novels include What Is Told, The Ambassador of the Dead and The House of Widows. He was the founding editor of Agni magazine and Arrowsmith Press. An associate professor in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts, Melnyczuk also teaches at the Bennington College Writing Seminars.

Where did Smedley (Jonathan) come from, as character as well as novel?

I'd been doing a lot of family-care, but one day I found myself in the Cambridge Public Library reading Aubrey's Brief Lives. You know, that 17th century gossipfest in the form of biographical sketches of Aubrey's literary friends and acquaintances, including poets Milton, Andrew Marvell, and Richard Lovelace. And suddenly I heard a voice making wisecracks about all the secret stuff Aubrey couldn't tell us about his pals--the sort of thing his peers could not have approved of openly: adultery, stealing from the till, radical doubt. I laughed out loud. I needed laughter more than anything at the time, so I decided to tune into that voice, see what else it had to say. Turned out to belong to a randy 15-year-old Cambridge kid who'd just been bounced out of school. And I had to find out why.

"I'm lucky to be alive," he writes to begin his punishment essay assignment. Although not the "official" first line of the novel, it's still an essential portal. How did those words find you?

As I said, it was a time in my life when I wanted some of what Jonathan had: irreverence, fearlessness, no thought for tomorrow. In short, the joyful and necessary obliviousness of extreme youth. Seeing the world through Jonathan's eyes let me see the 21st century in an entirely different way. What has it been like to grow up in a country permanently at war, with much of the world aflame?

On the other hand, it was a joy to recreate some of my own first memories and impressions of the seismic event that is Manhattan: to enter that city for the first time, again. And then to re-experience a kid's initiation into love, to watch him struggle to distinguish between it and lust, to try to find the words for that: delicious. Some of my favorite scenes, which were among the hardest to write, are the ones surrounding his meeting with his unexpected crush, Beyah. I wanted to get across the electricity of desire rippling under the skin, flaring up, burning us. That we rise from love's ashes is a miracle, no?

We learn early in the novel that Smedley has gotten in trouble for initiating a horrid "prank" on one of his friends. It's all the more shocking because he runs with a pretty diverse group. How did you conceive this?

We learn early in the novel that Smedley has gotten in trouble for initiating a horrid "prank" on one of his friends. It's all the more shocking because he runs with a pretty diverse group. How did you conceive this?

Without giving too much away, Jonathan and a friend pull a "prank" on a bandmate who happens to be African-American. It was something the characters did on their own--as characters will, when you set them in motion and step back. The boys were not aware of the racial overtones of their actions, but I was. What they did mirrors some of the insanity rippling through our culture these last several decades. Almost inevitably, kids act out the zeitgeist.

Smedley refutes all claims that his is "a coming of age story," but I think every novel is to some degree, regardless of the calendar age of the narrator/protagonist. We are forever coming of age. Would you agree or disagree?

"Identity" is always a fragile construct. In our age, however, it's become startlingly fluid almost overnight. Of course, it hasn't happened overnight. The truth of who we are has been working its way to the surface for a long time. Transparency has been a big word this last decade. There's a way in which all reality is becoming more transparent, gradually revealing what is, where we come from, what we're made of. Consider not only our maneuverability across genders, or the crazy discoveries of science. In our time, the animals themselves are trying to speak to us--or maybe it's that we are, for the first time in a long time, learning to listen again. I don't know, of course, but I think they're saying: watch out!

What's constant in the desire realm is desire. What's less locked down than people expected are aspects of ourselves some thought immutable: gender, religious faith, even our genes are spliceable.

Discoveries in quantum mechanics, loop quantum gravity, thermodynamics, and so on show us that space isn't empty and that matter, at the very tiniest level, can't decide what it is: wave or particle? Its identity is determined by the particles to which it relates.

I know a lot of gifted adult readers who were also precocious readers in their youth. As someone whose adolescent reading tended to lean heavily on comic books, I'm curious about your youthful reading life.

It was all over the place. I too was an avid reader of comic books, had the earliest Spidermans, as well as the Fantastic Four. I loved Mad Magazine and subscribed to Famous Monsters of Filmland, edited by Forrest J. Ackerman--remember that? How I wished I had an allowance which would have enabled me to buy a Wolfman mask.

On the other hand, my mother, a voracious reader, not only had me memorizing poems in Ukrainian, she also gave me books by some great writers few people read anymore, including Selma Lagerloff, Knut Hamsun, Rabindranath Tagore, and so on. I wanted to salute a few ancestors, say thanks.

Smedley is able to shut out digital intrusions when he wants to, but he also has (and I'm being slightly facetious) a kind of 140-characters-or-less approach to lit crit in writing the punishment essay. To what extent is Smedley an outlier as a child of the digital age?

I didn't see him as an outlier. He's equipped with all the technology a kid could want: an iPhone, an iPad. But in the last quarter of the novel, as he's pursuing his Beatrice, he either forgets or loses them. Pushed squarely back into his body, without the escape hatches or wormholes technology offers, he's forced to look at and interact with the world around him in a different way.

Again, this just happened as a matter of course. I didn't set out to show Jonathan online and off. But when he lost his iPhone I realized it changed him. Without our devices filtering encounters, we interact differently. In Jonathan's case, because he was born with all these toys always at hand, the experience is revelatory. He's naked to the elements. He sees and feels things he's missed before. And he's missed a lot.

In what ways is this novel different from your previous work? Similarities?

My first three novels all dealt with some aspect of the refugee/immigrant experience. My parents fled Ukraine during World War II. They spent five years in a refugee camp before getting permission to come to the United States. The trauma of the war was passed on to the children of everyone involved in it. Much of the world came to in 1945 suffering from PTSD, which was never treated. The American soldiers who came back from the war were victims as surely as the millions in Europe who endured bombings and the destruction of cities and communities. That offered a lot of material. But one day I decided I was through with it.

Making a privileged WASP my main character gave me the freedom of the mask--I've said before that this is my most personal book. Maybe because I'm still a randy 15-year-old at heart.

In considering what the unusual band of writers he chooses to explore might have in common, Smedley realizes they "had to deal with whatever world they woke up in. They had two choices: speak up, or play dead." Words to live by?

Why not?

Askold Melnyczuk: 'Speak Up, or Play Dead'

Askold Melnyczuk's latest novel, Smedley's Secret Guide to World Literature (PFP Publishing), has an intriguing subtitle: "By Jonathan Levy Wainwright, age 15." Jill McCorkle praised the young narrator as someone who "immediately charms the reader with his brilliant literary observations and insights, but what really steals the heart is that it comes on a wave of adolescent angst we all recognize--hormones and family problems and pop culture fuel this difficult journey while great and sometimes forgotten literary voices educate and shine light on his young and vulnerable heart." I agreed and had a few questions for the author behind that narrator. Melnyczuk's previous novels include What Is Told, The Ambassador of the Dead and The House of Widows. He was the founding editor of Agni magazine and Arrowsmith Press. An associate professor in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts, Melnyczuk also teaches at the Bennington College Writing Seminars.

Askold Melnyczuk's latest novel, Smedley's Secret Guide to World Literature (PFP Publishing), has an intriguing subtitle: "By Jonathan Levy Wainwright, age 15." Jill McCorkle praised the young narrator as someone who "immediately charms the reader with his brilliant literary observations and insights, but what really steals the heart is that it comes on a wave of adolescent angst we all recognize--hormones and family problems and pop culture fuel this difficult journey while great and sometimes forgotten literary voices educate and shine light on his young and vulnerable heart." I agreed and had a few questions for the author behind that narrator. Melnyczuk's previous novels include What Is Told, The Ambassador of the Dead and The House of Widows. He was the founding editor of Agni magazine and Arrowsmith Press. An associate professor in the MFA program at the University of Massachusetts, Melnyczuk also teaches at the Bennington College Writing Seminars. We learn early in the novel that Smedley has gotten in trouble for initiating a horrid "prank" on one of his friends. It's all the more shocking because he runs with a pretty diverse group. How did you conceive this?

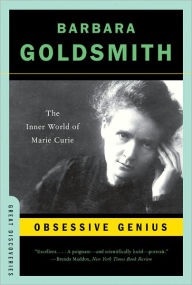

We learn early in the novel that Smedley has gotten in trouble for initiating a horrid "prank" on one of his friends. It's all the more shocking because he runs with a pretty diverse group. How did you conceive this? Journalist, editor and author Barbara Goldsmith died last Sunday at age 85. In her 20s, Goldsmith worked as a journalist in the art world. She profiled contemporary cultural icons like Audrey Hepburn and Pablo Picasso, creating award-winning work that would help her become a founding editor of New York magazine. She continued writing profiles and editing the magazine until the mid-'70s, when she "got tired of making other writers look good through my re-writing."

Journalist, editor and author Barbara Goldsmith died last Sunday at age 85. In her 20s, Goldsmith worked as a journalist in the art world. She profiled contemporary cultural icons like Audrey Hepburn and Pablo Picasso, creating award-winning work that would help her become a founding editor of New York magazine. She continued writing profiles and editing the magazine until the mid-'70s, when she "got tired of making other writers look good through my re-writing."