|

| photo: Rajib Saha |

Indrapramit Das (aka Indra Das) is a writer and artist from Kolkata, India, whose fiction has been published in Clarkesworld, Asimov's, Strange Horizons and Tor.com, and has been widely anthologized. He is an Octavia E. Butler scholar and a graduate of Clarion West 2012, and completed his MFA at the University of British Columbia. He divides his time between India and Canada, immigration willing.

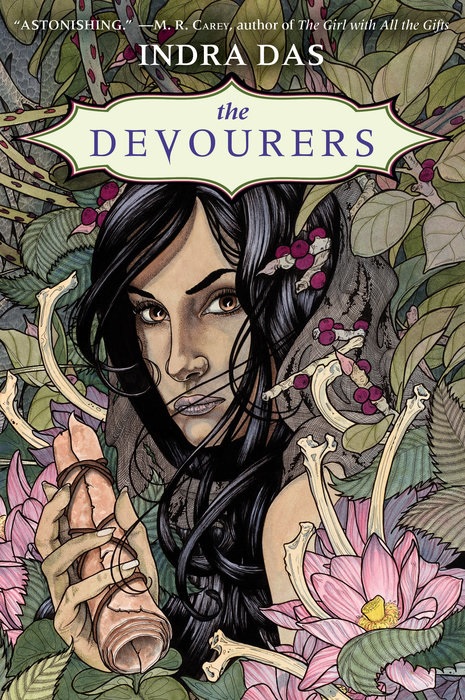

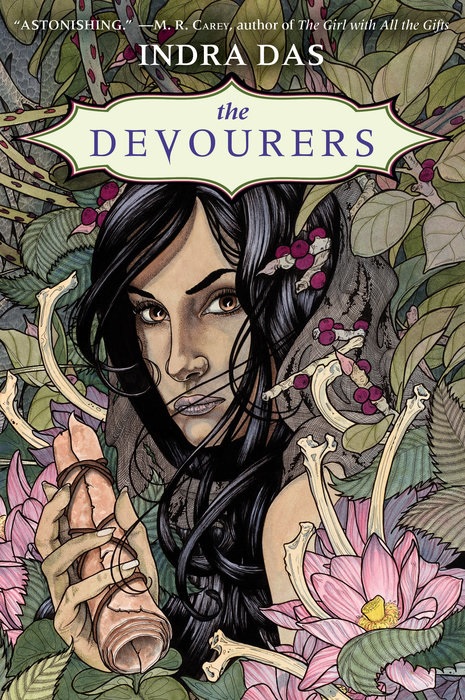

His first novel is The Devourers (Del Rey, July 12, 2016), a story of shapeshifters, magic and love, spanning from 17th-century Mughal India to 21st-century India, that stands out for dreamlike, haunting fantasy.

Reading your book, I had the feeling that there was another story beneath the surface, like one of the shape-shifters in the book. Was The Devourers a fantasy story from the start that became more, or was it the other way around?

That's an astute observation, because the process of writing The Devourers was in a way the novel having a conversation with itself. And myself.

The novel started as some werewolf stories I wrote during college, many years ago--and they were very male-centered, with the only women being a) prey for a werewolf b) a prostitute who is raped so that a male predator can come to terms with his own predatory nature. I was very young, and unpublished at the time, and still had a lot to learn about writing readable, good, complete stories (I still do, but I'm a bit better now). Those characters remain in the final novel--but the novel was woven around questioning how easily I, as a straight male writer, slipped so comfortably into using this misogynistic narrative device of taking away the voice of women, even while exploring violence against women (and ostensibly questioning and criticizing it). It's an essentially egotistical and harmful exercise in storytelling: male writer congratulates himself on condemning the existence of sexual violence by using it as an easy plot device for emotional (or nihilistic) impact. It's a pat on the back that doesn't engage with how we're all complicit in perpetuating cultures of sexual violence, misogyny and bigotry, doesn't engage with how we think about the place of violence in our societies. I can't say how well the novel that I ended up writing engages with these ideas, of course, but I tried, which my earlier, younger self, did not, at least not very hard.

Years later, writing my MFA thesis, I used those stories as seeds for a novel, and began to question the tropes of my early writing as I went along. Cyrah, the rape survivor at the heart of the novel's historical narrative threads, came alive when I realized how absurd it was to not give her a POV. She ceased to become just a plot device for male catharsis, and her voice became a substantial part of the novel. She's now honestly one of my favourite characters (that I've written).

There's also another aspect to this answer, in that those early stories were fantasy, but ambiguously so--the reader never saw the "second selves" of the shapeshifters. The shapeshifters were representations of humanity's ability to shape their own realities through story--they could be delusional, or talking about shapeshifting on a symbolic and cultural level, or real shapeshifters. The reader was to decide. I was inspired by the fact that people genuinely believed in werewolves as a legitimate threat, as entirely real, not that long ago. There are still people who believe in supernatural monsters, after all, all over the world. So my approach to "realizing" these myths was different.

Once I started writing the novel, though, it felt like a shame not to really show the magic inherent in these mythic narratives, and the whole thing shed its ambiguous skin to become the fantasy novel it wanted to be. Considering that the novel deals with such heavy, dark themes, I felt a need to give it some unabashedly non-realist vibrancy to shake off the grimdark muck of human nature.

There are parallels in the story to what's happening with the political climate in the United States. I imagine this book was largely finished when the current election commenced, but was there an intent on your part to address broad political themes?

There are parallels in the story to what's happening with the political climate in the United States. I imagine this book was largely finished when the current election commenced, but was there an intent on your part to address broad political themes?

The book was written long before this current U.S. election cycle--I was finishing up the first draft when President Obama had a year left of his first term. But yes! I very much wanted to address broad political themes, though I didn't know this until I started writing the first draft and really grappling with it, when I realized Alok was bisexual and attracted to the stranger, and Cyrah was going to be telling her own story. The book then showed itself to me, as it were, as an exploration of identity, gender, sexuality and violence. Of course, I wasn't thinking just about the political climate of the United States, but of India and the world, as an Indian citizen and at-the-time resident of Canada (and ex-resident of the U.S.), and pretty much permanent immigrant. (I'm currently in India, but want to return to Canada, and ideally move back and forth--easier said than done, especially as a not-rich brown person.)

Right now, there's an international dialogue about how we need feminism, and need to address the human rights of women, of LGBTQIA populations and of marginalized people all around the world, about how the weight of injustice and bigotry our global systems of commerce, learning, and entertainment are built upon is becoming entirely unsustainable. It's breaking the back of all our societies and cultures, and of the anthropocene Earth itself.

This new and visible dialogue is all because of the Internet, which also gives virulent voice to everyone opposed to all the above--to the notion of social justice. But it's not a new conversation, even if the way we're having it is new, and seems more urgent. Civil/human rights struggles have been around since the dawn of human beings, I imagine. We've always mistreated each other, hated each other, loved each other. We've always killed each other. We've always been dicks to women and people who don't stick to any one society's prevailing idea of sexual and gender norms. We've always been for and against social justice for populations we believe deserve it--or don't deserve it.

Which is why (I assume) The Devourers feels relevant to today's political climate: because these themes, about humanity trying to reconcile its creativity and violence, are universal.

Do you have plans to return to this world in future books?

I honestly don't know. There are definitely more stories to tell; a whole world of them, an entire alternate history of the world and its mythologies to explore. That said, I don't know when and if I'll want to tell more stories in this world, because of how much time I spent in it already. I want to explore new ones, you know? But I wouldn't rule out another book (or short stories) connected to The Devourers some day. --Matthew Tiffany, LCPC, writer for Condalmo and psychotherapist

Indra Das: Magic and Mythic Narratives

This anthology captures a compelling breadth of perspectives. Gerald Howard, executive editor of Doubleday publishing, considers the finer points of what makes a book successful, not least of which he owes to becoming a better reader over 37 years of doing so professionally. As Richard Nash, a publishing consultant and former head of Soft Skull Press, put its: "The more you read, the better you get at it, the more fun you have."

This anthology captures a compelling breadth of perspectives. Gerald Howard, executive editor of Doubleday publishing, considers the finer points of what makes a book successful, not least of which he owes to becoming a better reader over 37 years of doing so professionally. As Richard Nash, a publishing consultant and former head of Soft Skull Press, put its: "The more you read, the better you get at it, the more fun you have."

There are parallels in the story to what's happening with the political climate in the United States. I imagine this book was largely finished when the current election commenced, but was there an intent on your part to address broad political themes?

There are parallels in the story to what's happening with the political climate in the United States. I imagine this book was largely finished when the current election commenced, but was there an intent on your part to address broad political themes? In 1964, Ron Kovic joined the Marine Corps fresh out of high school. He volunteered for two tours of duty in Vietnam. On a reconnaissance mission in 1968, Kovic was shot twice: once in the foot and once in the shoulder. The second bullet injured his spine, leaving him paralyzed from the chest down. Back in the U.S., Kovic became a prolific peace activist, and was arrested at least a dozen times.

In 1964, Ron Kovic joined the Marine Corps fresh out of high school. He volunteered for two tours of duty in Vietnam. On a reconnaissance mission in 1968, Kovic was shot twice: once in the foot and once in the shoulder. The second bullet injured his spine, leaving him paralyzed from the chest down. Back in the U.S., Kovic became a prolific peace activist, and was arrested at least a dozen times.