|

| photo: Peter Prato |

Dr. Daniel J. Levitin is a James McGill Professor of Psychology, Behavioural Neuroscience, and Music at McGill University in Montreal, and Dean of Arts and Humanities at the Minerva Schools at the Keck Graduate Institute in California. He is the author of This Is Your Brain On Music (2006), The World in Six Songs (2008) and The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload (2014). His new book is A Field Guide to Lies: Critical Thinking in the Information Age (reviewed below).

What led you to write this book?

For 15 years at McGill I've been teaching a course for senior honors students that's effectively a course in critical thinking. And a great deal of what we're doing at Minerva is trying to embed critical thinking in the curriculum starting in the freshman year. Our dean of the faculty, Stephen Kosslyn, was the dean of social sciences at Harvard, and he had several conversations with Harvard's administration about critical thinking--"Do you teach critical thinking at Harvard?"--and the answer was always "Yes." Stephen would say "Where, what classes?" And they'd say "Well, there's not really a class dedicated to it, but students pick it up." I think that critical thinking is something that is undervalued; there's the need to sit down and teach it. What made me want to write A Field Guide to Lies is watching the kind of conversation we've been having in the U.S. around politics. It used to be the two sides listened to each other. And it used to be that you could get a reasonable person to change their mind if you gave them information that was compelling and rigorously sourced. That's not happening anymore. And I think that the whole idea of representative democracy is that the voters need to be informed. And if they're not, they're going to make choices that are against their own interests or against the long-term interests of the country. That was what motivated me to write the book and write it now.

How did you choose the tools in this book?

Some of them come from neuroscience, some from information science, some from the Kahneman and Tversky camp. Danny Kahneman wrote this great book called Thinking Fast and Slow that summarized a lot of his work, and I worked in his lab as a student. I think the tools that are introduced in my book are typical of what one would get by going to law school or journalism school or getting scientific training.

I was reading it thinking, wow, these methods are great, but wondered about the barriers that some people might have to picking them up. One is the aversion to math. What would you say to people who hate getting involved with numbers?

I was reading it thinking, wow, these methods are great, but wondered about the barriers that some people might have to picking them up. One is the aversion to math. What would you say to people who hate getting involved with numbers?

I understand math aversion. And I think almost everybody has it at some point. I think that we can have numerical literacy, the same way we can have information literacy, without necessarily being a math whiz. What I would say is: just look at the numbers and without doing any addition or subtraction or working out any equations, ask yourself a couple of things. First, are they plausible? The person who cut my hair the other day said she had read that there are 10 billion people on the planet without Internet access and we should do something about that. Now, I don't keep up with world population statistics, but I think it's somewhere between seven and eight billion. I don't have to know the exact number. I know that it's not 10 billion, or I can look it up fast enough. And I know that some people do have Internet, so it can't be that 10 billion don't. That's a plausibility issue, you don't need to use much math.

The second question is: Do the numbers support the claims? I think the most egregious example of this played out in Congress with the Planned Parenthood graph. In a congressional session, a graph is put on display, and it looks like Planned Parenthood has been drastically cutting funding for cancer screenings and drastically increasing the funding for abortion. But if you look at the numbers printed on it, you see that the graph has been incorrectly drawn to make a visually striking point that doesn't agree with the numbers. I think even a mathphobe can get their head around that.

Another barrier to critical thinking might be some people's mistrust of information sources.

Setting aside conspiracy theorists... I think we do have to trust people, and society and science and culture are based on that. I've never seen a gene, I've never seen an atom--I'm taking people at their word who seem credible to me. You have to satisfy yourself that within the limits of knowledge and current thinking, these people are experts. It's not always the case but people who work for legitimate institutions and have been trained by legitimate institutions are a better bet. I might ask how you know that or what your evidence is, I might check it with a second or a third person or do a bit of research myself to try to get some corroboration.

This is why we get second opinions in medicine, and for that matter we may get second opinions from an auto mechanic or a construction contractor. People who are well intentioned and well trained can have differing views, and you do need to make a little more effort than you used to, to sort things out. But we're saving so much time because the process of acquiring information has become almost instantaneous. All that time we're saving from not having to go to the library and find physical books and articles--we now need to spend at least some of it tracking these things down.

You were saying the U.S. political situation partly inspired this book. How do you critically approach politics?

I think the first thing to do is to listen to what politicians are saying, and then read sites like Politifact and the Washington Post's Fact Checker. Of course, their reporters have their own political biases, but I think their editors are careful to minimize those biases. I also think it's important to realize that the two major parties have complicated platforms, and it may be the case, particularly in smaller or local elections, that a particular candidate is promoting things you like and they are not in the party you usually vote for. I would be open to that possibility.

And as someone who has devoted so much of my life to education, I think that knowing certain biases exist is a good way to prevent them from influencing you too much. One of them is confirmation bias. I think a whole bunch of people in the country made up their minds a long time ago about which presidential candidate they were going to support because they had a visceral reaction to one or the other. And I think that having made up their minds, some voters don't take in any more information. If something bad is said about their candidate, they say, yeah, that's bad, but my candidate is better than the alternative. If something good comes out about the opponent, they say the media's biased or one good thing isn't outweighed by all the terrible things.

How do you break that attitude down?

You try to be open-minded. Whoever the candidate is, you accept the possibility that the one you don't favor might win and it might be good to know a little about that person. --Sara Catterall

Daniel Levitin: Tools for Critical Thinking

I was reading it thinking, wow, these methods are great, but wondered about the barriers that some people might have to picking them up. One is the aversion to math. What would you say to people who hate getting involved with numbers?

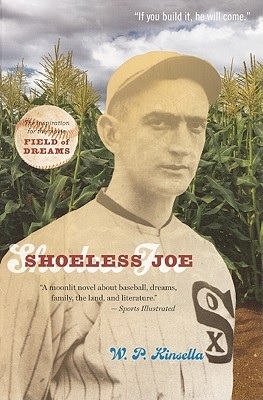

I was reading it thinking, wow, these methods are great, but wondered about the barriers that some people might have to picking them up. One is the aversion to math. What would you say to people who hate getting involved with numbers? Canadian novelist W.P. Kinsella, author of Shoeless Joe, which became the 1989 Kevin Costner film Field of Dreams, died last week at age 81. Kinsella's novels and short stories were primarily about baseball, with dashes of magical realism, and about the plight of Native Canadians. His first published book, Dance Me Outside (1977), is a collection of 17 stories set on a Cree Indian reserve in Central Alberta. Shoeless Joe (1982) and The Iowa Baseball Confederacy (1987) remain Kinsella's most enduring works. In 1997, he suffered a brain injury during a car accident that kept him from publishing another novel until 2011's Butterfly Winter. Kinsella died via doctor-assisted suicide after suffering from diabetes for many decades.

Canadian novelist W.P. Kinsella, author of Shoeless Joe, which became the 1989 Kevin Costner film Field of Dreams, died last week at age 81. Kinsella's novels and short stories were primarily about baseball, with dashes of magical realism, and about the plight of Native Canadians. His first published book, Dance Me Outside (1977), is a collection of 17 stories set on a Cree Indian reserve in Central Alberta. Shoeless Joe (1982) and The Iowa Baseball Confederacy (1987) remain Kinsella's most enduring works. In 1997, he suffered a brain injury during a car accident that kept him from publishing another novel until 2011's Butterfly Winter. Kinsella died via doctor-assisted suicide after suffering from diabetes for many decades.