_Colin_Thomas.jpg) |

| photo: Colin Thomas |

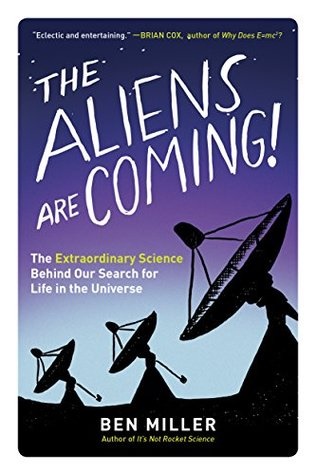

Ben Miller is a BAFTA Award-winning actor and comedian living in London best known for being one-half of the comedy act Amstrong and Miller. He describes himself as "a mutant ape living through an Ice Age on a ball of molten iron, circulating a supermassive black hole." Miller also happens to be a Cambridge-trained physicist who plays the disembodied brain Professor McTaggart on ITV's It's Not Rocket Science. His second science-related book, The Aliens Are Coming: The Extraordinary Science Behind Our Search for Life in the Universe (available in paperback from The Experiment), provides an entertaining and thought-provoking look behind the scenes at our search for extraterrestrial life.

Despite being far removed from your studies as a graduate student in physics during the late 1980s, you have maintained a solid grasp of modern physics and biology while enjoying a career as a comedian. What compelled you to return to your roots?

It was a midlife crisis. I suddenly had the awful feeling of unfinished business. I started a Ph.D. in physics at Cambridge--in fact, I did three years of research--but never finished it. Then a couple of years ago I started to get this yearning for science. Some men would have bought a sports car, others would have taken up the guitar; I decided to write a book about the real science of aliens.

For a physicist, you devote considerable thought to microbiology. What does science tell us about the ability of microbes to survive in extreme environments on Earth, but not on Mars, Mercury or one of the moons of Saturn, for example, and of the possibility that Earthlings originated on another planet?

Microbiology tells us that life is extremely tenacious. It finds a way. Whereas we were once convinced there could be no microbial life in the outer reaches of the solar system, now we aren't so sure. We have also learned that the planets of the solar system aren't hermetically sealed; on the contrary, they are intimately interconnected. Asteroids collide with Mars, for example, and then end up on Earth. Early Mars was, in some ways, a more hospitable planet than ours. It remains possible that life may have started on Mars, then hitched here on a space rock. And, most excitingly of all, it remains possible that in the liquid ocean beneath the icy crust of Saturn's moon Enceladus, alien microbes are thriving.

Earth seems unique in its ability to support so many forms of life. If there are many Earth-like planets out in the universe, why has there been no sign of intelligent life?

Well firstly, I'm not sure that Earth is unique in its ability to support life. As we are seeing from our latest telescopes, there are lots of planets out there that could do the job just as well, if not a little better. The really important question is, is Earth the only place where life has started? Certainly, at the moment, it's the only place we know of, but then we haven't done an awful lot of looking. As to why there's been no sign of intelligent life, well, like all good relationships, it's down to timing. Intelligent civilisations are rare, and separated by a great deal of time and space. If the nearest one is 10,000 light years away, it's seeing the Earth as it was before human civilisation. If it's 100 light years away, it's only just started to pick up our early experiments with radio.

In the chapter "Planets," you open up the line of inquiry beyond hard science to include pop culture references, concluding that culture provides the most important frame of reference in understanding Earthly life. Yet culture is also a man-made artifact. What would happen if "culture" couldn't be a common mode of communication with newly discovered lifeforms?

In the chapter "Planets," you open up the line of inquiry beyond hard science to include pop culture references, concluding that culture provides the most important frame of reference in understanding Earthly life. Yet culture is also a man-made artifact. What would happen if "culture" couldn't be a common mode of communication with newly discovered lifeforms?

And that, in a nutshell, is the whole problem. If we don't share a culture with the entity we are trying to communicate with, it is much harder to decode its messages. When Jean-Francois Champollion finally translated the Egyptian hieroglyphs, it was due in part to the existence of the Rosetta stone. On this stone was the same piece of text written in three languages, one of which was hieroglyphs, and another ancient Greek. But of course Champollion was also assisted by his knowledge of ancient Egyptian civilisation. When we receive an alien message, how will we decode it, with no knowledge of the culture that shaped it?

Is it fair to assume that if life did exist "out there," those beings would be as advanced as we are?

My understanding is that conditions have been right for life in spiral galaxies like the Milky Way for roughly five billion years. Before that, there was too much high-energy radiation around. So the important question becomes, what's the average length of time it takes to evolve a civilisation? If Earth is average, it takes about four billion years. So there might be civilisations out there that are a billion years older than ours. There might be civilisations younger, of course, but we wouldn't be able to detect them because they wouldn't yet have developed radio communication. Which all shakes down as: if we are contacted by aliens, we'd better not talk down to them.

You pose the possibility of Earth humans being so advanced as to provoke the galaxy to "wake up." Why do you believe this?

If there's one thing we know about the human race, it's that we are explorers by nature. Anatomically modern humans left Africa sometime within the last 200,000 years, and have now populated the entire planet. We have set foot on the Moon, and we are planning missions to Mars. The next generation of telescopes will search for our nearest Earth-like planets. When we find one, I am sure of one thing: someone, somewhere, will hatch a plan to go there. The human diaspora will have begun.

How do we know that certain universal scientific and linguistic rules will carry over across universes, that alien technologies will evolve along the lines that ours has and that truth of our physical models extrapolates beyond what is known?

We don't, but we are probably better off looking for civilisations like our own as we have more chance of recognising them. One thing we will almost certainly have in common with our alien neighbours is the fundamental structure of the universe. They will have the same building blocks of matter such as the proton, neutron and electron, and be familiar with the same periodic table of chemical elements and their compounds. But when we imagine civilisations that are technologically evolved way beyond our own, we have no idea what we might have in common. Maybe very little. They may be out there, clearly visible in the galaxy, but we have no idea what we are looking for. Does an ant, sitting on your foot, have any idea that you exist? Possibly. Does it have any inkling that Coldplay has a new album out? I doubt it. And yet Coldplay is everywhere.

What are your thoughts on the recent discovery of Proxima B, an Earth-like planet orbiting Proxima Centauri?

It thrills me because it shows yet again that small rocky planets like ours are common. Though of course Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf star and so Proxima B isn't truly Earth-like. We urgently need to search our nearest sun-like stars to find out if they have Earth-like planets in Earth-type orbits, and the next generation of telescopes will be able to do just that. After all, Earth is the one place where we know life exists, so it makes sense to start looking for planets that are truly Earth-like in all respects. The data we have so far tells us that the nearest such planets may be as little as 12 light years away. Imagine that. The nearest alien civilisation might be just about to catch the first season of Arrested Development. Lucky entities.

Should we expect to hear of aliens in any of your upcoming comedy routines?

Absolutely not. All of this is too far-out for comedy. No one would believe it. --Nancy Powell, freelance writer and technical consultant

Ben Miller: The Real Science of Aliens

What surprised you most in your interviews?

What surprised you most in your interviews?

_Colin_Thomas.jpg)

In the chapter "Planets," you open up the line of inquiry beyond hard science to include pop culture references, concluding that culture provides the most important frame of reference in understanding Earthly life. Yet culture is also a man-made artifact. What would happen if "culture" couldn't be a common mode of communication with newly discovered lifeforms?

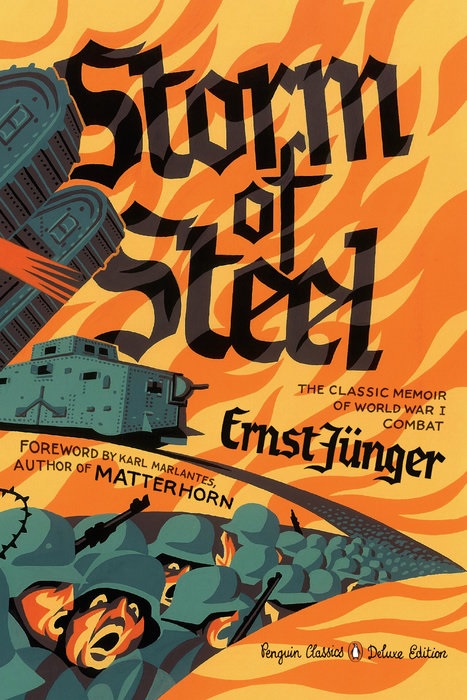

In the chapter "Planets," you open up the line of inquiry beyond hard science to include pop culture references, concluding that culture provides the most important frame of reference in understanding Earthly life. Yet culture is also a man-made artifact. What would happen if "culture" couldn't be a common mode of communication with newly discovered lifeforms? At the outbreak of World War I, Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) volunteered as an infantryman in the German army. He received the first of many wounds in April 1915 and, during his recovery, decided to become an officer. As a lieutenant, Jünger led an infantry platoon through several cataclysmic battles on the Western front, where he was well known for daring nighttime patrols and offensive initiatives. Jünger survived 14 wounds, the last of which was a shot through the chest that nearly ended his life during the 1918 Spring Offensive. He was awarded the Pour le Mérite, the German Empire's highest honor, one of just 11 given to infantry commanders during the war.

At the outbreak of World War I, Ernst Jünger (1895-1998) volunteered as an infantryman in the German army. He received the first of many wounds in April 1915 and, during his recovery, decided to become an officer. As a lieutenant, Jünger led an infantry platoon through several cataclysmic battles on the Western front, where he was well known for daring nighttime patrols and offensive initiatives. Jünger survived 14 wounds, the last of which was a shot through the chest that nearly ended his life during the 1918 Spring Offensive. He was awarded the Pour le Mérite, the German Empire's highest honor, one of just 11 given to infantry commanders during the war.