|

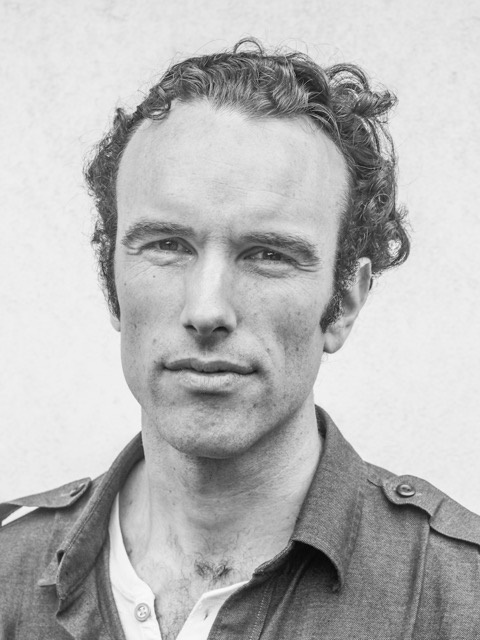

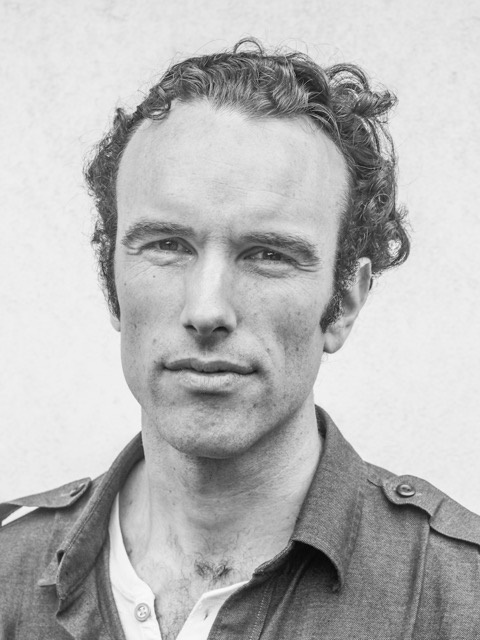

| photo: Peter van Agtmael |

Elliot Ackerman is the author of Green on Blue, a former White House Fellow and a former Marine who served five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, where he received the Silver Star, the Bronze Star for Valor and the Purple Heart. His new novel, Dark at the Crossing (reviewed below), is set on the border between Turkey and Syria during the ongoing Syrian Civil War and follows an Iraqi American trying to cross the border and fight for the Free Syrian Army. Ackerman lives in Istanbul, where he has covered the Syrian conflict since 2013.

Most of Dark at the Crossing takes place in Turkey or in the protagonist's memories of Iraq and the U.S. Why take such an indirect approach to the conflict in Syria? Is the novel even about Syria?

The Syrian Civil War (or revolution, depending on your perspective) is the backdrop of the novel, but I don't believe it is what the novel is about. My ambition for the book was to tell the story of a failed revolution through the prism of a failed marriage. Why this choice? Because while spending significant time covering the war in Syria, what became evident was how so many of the democratic activists who had taken to the streets to protest the regime of Bashar al-Assad were suffering from a kind of heartbreak in the wake of their failed revolution. They had given themselves completely to the cause of bringing democratic reforms to Syria and had seen their efforts end disastrously. They had upended their lives to support the revolution at great personal expense and so many of them had fallen in love with its ideals. The notion of upending one's life for an ideal is also experienced when two people come together and marry. A marriage is, in its way, a revolution of sorts. And just as with actual revolutions, when a marriage fails, it leaves behind significant wreckage. The novel explores how the principal characters not only deal with the wreckage left behind by their revolution, but also the wreckage left by their failed marriage. Parity exists between these two emotional arcs.

Your previous novel, Green on Blue, followed a young Afghan who fights with a U.S.-sponsored militia. In Dark at the Crossing, Haris Abadi is haunted by the time he spent as a translator for U.S. forces in Iraq. Are you particularly interested in the moral cost of collaborating with an occupying foreign power?

I think it's important to keep in mind that Haris Abadi is an American and an Iraqi. In the opening pages of the novel, the reader learns how he earned his American citizenship. His name was a very intentional choice. Haris with one "r" is an Arabic name, but with two, it is a Western one. I have an interest in characters who are torn between two separate identities, who perhaps lead double lives. The result is incompleteness, an emptiness within. This also results in the human heart coming into conflict with itself, which is the only thing worth writing about.

Haris Abadi wants to join the Free Syrian Army and fight Assad, but he encounters characters aligned with the Daesh, also known as ISIS. Was it difficult to empathize with or, at the very least, understand these men?

Haris Abadi wants to join the Free Syrian Army and fight Assad, but he encounters characters aligned with the Daesh, also known as ISIS. Was it difficult to empathize with or, at the very least, understand these men?

As a novelist my job is to empathize with my characters, particularly the ones who at face value feel most distant from me. When I envision them, I am trying to make their case as though they were standing before God explaining themselves. But this obviously takes some work. With regards to the characters who were members of the Islamic State, I became friendly with one former member of Al-Qaeda in Iraq who actually fought in al-Anbar province the same time I was there fighting as a Marine. The two of us met in a refugee camp along the Syrian border and, oddly enough, became friends. We were soon getting together every few months to talk and have tea, sort of an impromptu VFW meeting in south Turkey. We would usually discuss the old days fighting in Iraq on opposite sides, and recent events in the region. Although he was no longer fighting, he still believed in the fundamental strains of Islam that fuel radical groups like the Islamic State. This led to many debates between us. Did I agree with him on most issues? No. Could I understand how as a Sunni Arab who had spent time in prison in Bashar al-Assad's Syria and who had been disenfranchised within his country, why he would turn to religion and radicalization? Of course, I could.

Dark at the Crossing is not only about war but about the kinds of love that develop in its shadow. What characterizes relationships that develop in these seemingly impossible conditions? I'm thinking not only of romantic relationships, but of the strange bond between Haris and an American Special Forces soldier named Jim.

War by definition is a manifestation of extreme emotion. It is one group of people believing enough in some cause that they are willing to kill for it and perhaps to die for it. (It is also the story of innocents trying to survive those groups of believers.) The relationships that develop in this heightened emotional space are of an extreme intensity. This is an environment that strains relationships--even the most basic: mother to child, husband to wife, etc.--pushing them to their breaking points, or else soldering them into bonds of incredible durability.

You write: "When the last of the Free Army dissolved, the revolution would finally be over. Then the war could begin." At this point, the Free Army seems to exist mostly in a nominal sense. Is the revolution over? Do the hopeful vestiges of the Arab Spring still exist in any meaningful way?

It depends on who you speak to. And this is obviously a loaded question when discussing the revolution with Syrians. I had one Syrian friend in particular, Abed, to whom the book is dedicated. He was a democratic activist in the revolution's early days who was forced to flee the country by the regime. Stranded in Gaziantep, or Antep as most locals refer to it, he and I would often eat dinner together. On any given night, we could be sitting down and ordering our meal while he insisted in our discussions that the revolution was not over, that the Free Army could still defeat Assad if properly supported by the West. However, by the time our meal was over and we were having our tea, he would be lamenting that the entire revolution was a mistake, that he wished he could take it all back, that he and the other activists had never gone into the streets in protest, that he had destroyed his own home. Whether the revolution is over is not just a political question. I came to learn that it is also a deeply personal question, one so many Syrians have wrestled with and continue to wrestle with as they decide whether or not to abandon their country and craft a new life in the diaspora or to stay engaged with political developments at home.

As an American writing about Iraqi and Syrian expatriates, how did you make sure that you portrayed your characters realistically and respectfully?

When writing any character in a novel, I am by definition writing about someone who is outside of my experience. It is my job to become as close to that character as I possibly can, to do my best to understand who they are. If a character shares my nationality, that doesn't necessarily mean that I know them better than one who does not. The unknown variables for every character are different. When I read, the authors that I admire most open up through their imaginations the interior lives of people that would otherwise remain inaccessible to me.

I happen to be a veteran and a novelist. Some years back there was a great deal of controversy among Iraq and Afghan war vets when certain novels came out that were written by authors who had never served in the military, particularly when those novels received a great deal of acclaim and when literary critics commented on their realism. Some in my community viewed this as an act of cultural appropriation by those non-vet authors, as if our stories were ours alone to tell and were somehow being robbed from us. I reject this view entirely. What fiction does, and what it does extremely well, is assert that all of us are part of an emotional collective. When I am reading a really excellent book, I feel something as I turn the pages. That is what good art does: it transfers emotion. Whatever the writer felt as they crafted their story is passed onto the reader. But if we begin to make rules that only certain topics can be breached by certain artists based on some experiential authority, then we are negating what the best art asserts: that we are, all of us, part of that very same emotional collective. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books

Elliot Ackerman: The Same Emotional Collective

Before you, says the narrator, "I was a flower with no pot./ I was a polka with no dot." "I was a tail without a wag./ Just a bean without a bag." Rebecca Doughty's Before You (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) captures the forlorn nature of each "before you" scenario with just the right amount of sadsack droopiness. "I was a bowl without a fish" is illustrated, suspiciously, with an empty fish bowl and a cat pawing the side of the glass. When the much-anticipated "you" does arrive, the tune changes: "You put the fizz into the pop./ You put the flip into the flop." A fizzy adult-to-adult valentine.

Before you, says the narrator, "I was a flower with no pot./ I was a polka with no dot." "I was a tail without a wag./ Just a bean without a bag." Rebecca Doughty's Before You (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) captures the forlorn nature of each "before you" scenario with just the right amount of sadsack droopiness. "I was a bowl without a fish" is illustrated, suspiciously, with an empty fish bowl and a cat pawing the side of the glass. When the much-anticipated "you" does arrive, the tune changes: "You put the fizz into the pop./ You put the flip into the flop." A fizzy adult-to-adult valentine. In Adam Rex and illustrator Scott Campbell's XO, OX: A Love Story (Neal Porter/Roaring Brook Press), Ox is utterly enamored with the starlet Gazelle and finally writes to tell her so: "Even when you are running from tigers you are like a ballerina who is running from tigers. I think that what I am trying to say is that I love you." Gazelle responds with a form letter. Ox persists, finally getting under her skin by lovingly implying that she might have a fault or two. Is her main fault that she "could never, ever love an ox?" Or could she be persuaded? (She can.)

In Adam Rex and illustrator Scott Campbell's XO, OX: A Love Story (Neal Porter/Roaring Brook Press), Ox is utterly enamored with the starlet Gazelle and finally writes to tell her so: "Even when you are running from tigers you are like a ballerina who is running from tigers. I think that what I am trying to say is that I love you." Gazelle responds with a form letter. Ox persists, finally getting under her skin by lovingly implying that she might have a fault or two. Is her main fault that she "could never, ever love an ox?" Or could she be persuaded? (She can.)  Mick Inkpen (the Kipper series) packs a surprising emotional punch with I Will Love You Anyway (Aladdin), a rhyming British import about unconditional love, expressively illustrated by his daughter Chloë Inkpen. A bulging-eyed pug is trouble, silently telling his beloved redheaded boy: "I steal your glove./ I steal your shoe./ I steal your socks./ They smell of you." He runs away, but the family retrieves him: "I don't do 'Sit!'/ I don't do 'Stay!'/ But I will love you anyway." Drop everything and find this wonderful book right now. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Mick Inkpen (the Kipper series) packs a surprising emotional punch with I Will Love You Anyway (Aladdin), a rhyming British import about unconditional love, expressively illustrated by his daughter Chloë Inkpen. A bulging-eyed pug is trouble, silently telling his beloved redheaded boy: "I steal your glove./ I steal your shoe./ I steal your socks./ They smell of you." He runs away, but the family retrieves him: "I don't do 'Sit!'/ I don't do 'Stay!'/ But I will love you anyway." Drop everything and find this wonderful book right now. --Karin Snelson, children's & YA editor, Shelf Awareness

Haris Abadi wants to join the Free Syrian Army and fight Assad, but he encounters characters aligned with the Daesh, also known as ISIS. Was it difficult to empathize with or, at the very least, understand these men?

Haris Abadi wants to join the Free Syrian Army and fight Assad, but he encounters characters aligned with the Daesh, also known as ISIS. Was it difficult to empathize with or, at the very least, understand these men? It's been 30 years since Scottish author Ian Rankin introduced the world to Detective Inspector John Rebus, an Edinburgh police officer and former SAS member with a curmudgeonly, sometimes misanthropic disposition. Knots and Crosses, the first of 21 Inspector Rebus mysteries, was written while Rankin was still a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh. It takes place in an Edinburgh terrorized by a serial killer strangling young girls. Inspector Rebus, between overindulging on drinks, cigarettes and women, investigates the murders, only to discover that his own family and military past are keys to stopping the killings.

It's been 30 years since Scottish author Ian Rankin introduced the world to Detective Inspector John Rebus, an Edinburgh police officer and former SAS member with a curmudgeonly, sometimes misanthropic disposition. Knots and Crosses, the first of 21 Inspector Rebus mysteries, was written while Rankin was still a postgraduate student at the University of Edinburgh. It takes place in an Edinburgh terrorized by a serial killer strangling young girls. Inspector Rebus, between overindulging on drinks, cigarettes and women, investigates the murders, only to discover that his own family and military past are keys to stopping the killings.