|

| photo: Danny Sanchez |

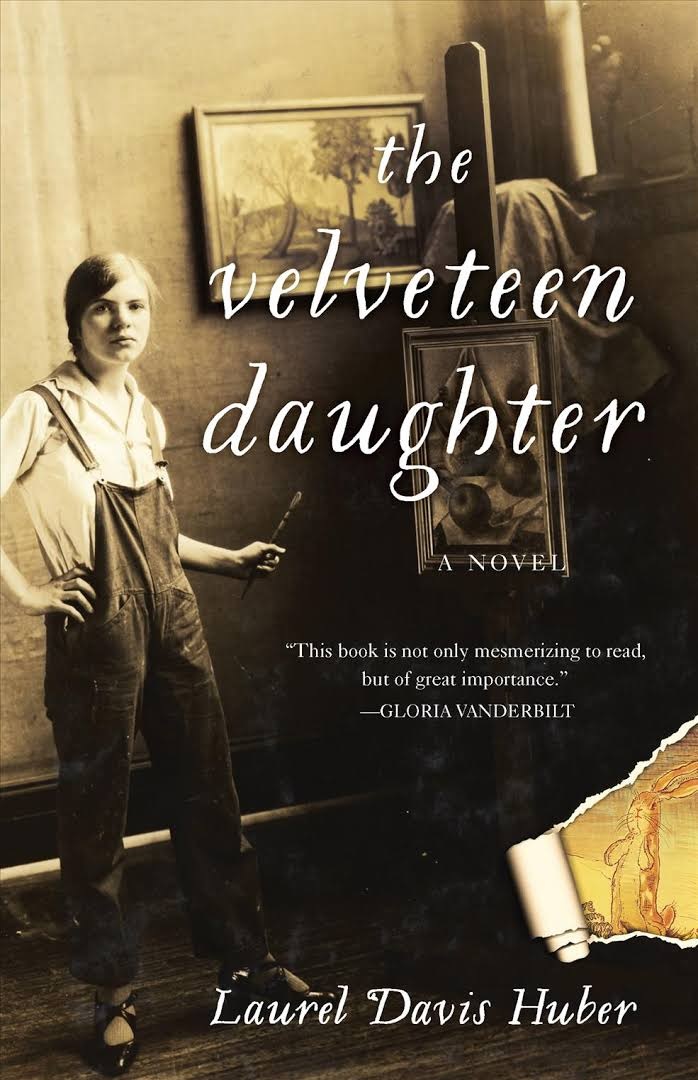

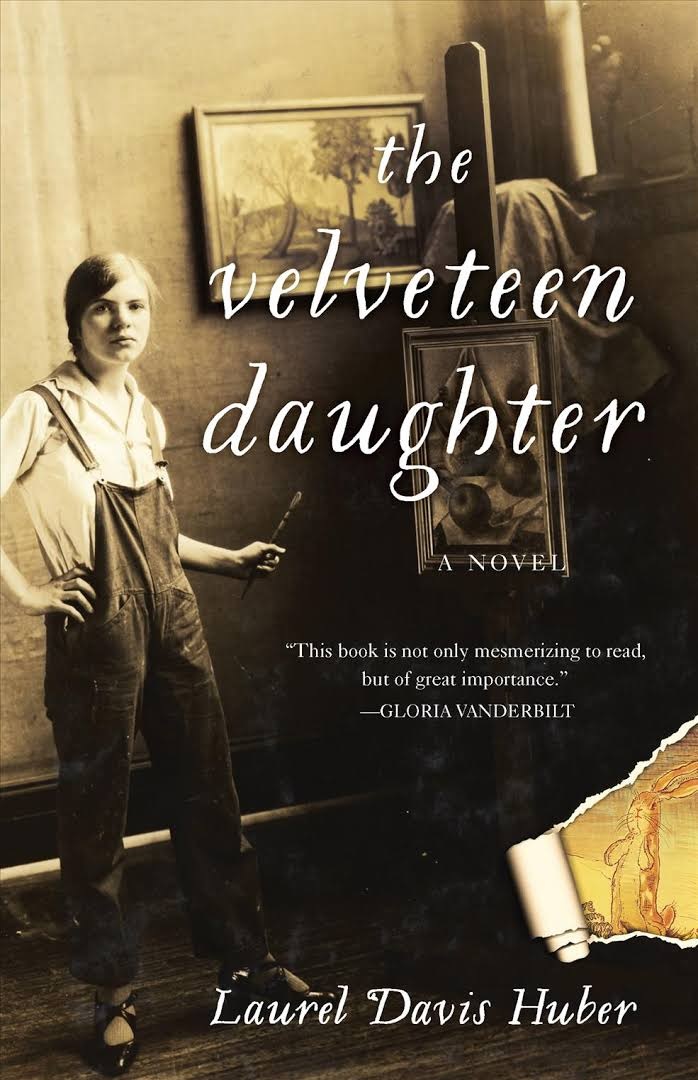

Laurel Davis Huber grew up in Rhode Island and Oklahoma. She has worked as a corporate newsletter editor, communications director for a botanical garden, high school English teacher and senior development officer for New Canaan Country School and for Amherst College. She and her husband split their time between New Jersey and Maine. The Velveteen Daughter (reviewed below) is her first novel.

What sparked the idea of The Velveteen Daughter? Have you always been a fan of Margery Williams Bianco and The Velveteen Rabbit?

Ironically, The Velveteen Rabbit was not a staple from my childhood. I remember so many delightful books my mother read to me--the Babar books, the Beatrix Potter tales and very early Dr. Seuss, like The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins and To Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. It was not until I was an adult that I first read The Velveteen Rabbit. What started me on my writing journey was a simple act of diversion. One summer day in 2006 I picked up an old ABC book from my childhood that had beautiful drawings, and for the first time noticed the name of the author/illustrator: Pamela Bianco. Idly, I wondered if she had written and illustrated other books. A quick Google search led to the discovery that she had been a famous child prodigy. Curious, I kept on looking. When eventually I found out--and it took a long while--that her mother was the author of The Velveteen Rabbit, I became obsessed with the story.

Was it difficult to research the lives of Margery and Pamela? For example, throughout the novel Pamela calls Margery "Mam." Did you find documentation that she used Mam instead of mother or mom, or was that creative license?

The use of the "Mam" moniker is a small bit of creative license. The truth is that Pamela almost always referred to her mother as "Mummie" or, even more frequently, "Bombom!" I'm afraid I felt these names would get tiresome quite quickly to readers. However, Francesco (Pamela's father) would refer to Margery in his letters to his children as "Mam" or "Mammy." So I did not make up "Mam" out of whole cloth. As for the research, I wouldn't say it was not difficult. It was time-consuming, but it was so much fun I didn't want it to stop. I traveled all over the country in search of letters and memos and photographs and artwork. At the back of the book there is a list of sources for those who may be interested.

Many glamorous and famous people make cameos in The Velveteen Daughter--Richard Hughes, Eugene O'Neill, the Gershwins. What was the best part of digging into the art and literary worlds of the early 20th century?

I had to restrain myself so that I didn't include too many famous names. The Bianco family lived in the center of Greenwich Village when it was at its height as the stomping ground for bohemian artists, writers and musicians. Edward Hopper lived right around the corner, Edna St. Vincent Millay also lived nearby, and, yes, the Gershwin brothers really did frequent Francesco's bookstore. A caricature published in Harper's Bazaar in 1922 shows Margery and Pamela surrounded by the fashion designer Erté, Stephen Vincent Benet and G.K. Chesterton, to name a just a few! During my research, I stumbled over one surprise after another. The most exciting discovery was handwritten letters that described in detail Pamela's wedding in Harlem; a close second was finding memos from the New Yorker archives detailing conversations with Pamela long after she had faded from the public view.

Why do you think Pamela's fame didn't last? Perhaps her art didn't stand the test of time?

Why do you think Pamela's fame didn't last? Perhaps her art didn't stand the test of time?

This is almost impossible to answer. I am neither a trained art historian nor an art critic, so I cannot judge Pamela's work in terms of its "worthiness" to stand the test of time. I do know two things: the first is that child prodigies rarely succeed in a big way throughout their lifetimes--they almost always seem to burn early and flame out fast; the second is that floating around "out there" there is an unknown society of writers, poets, artists and composers whose work is forgotten simply because of fate, and not for lack of brilliance. Pamela's work as a child was delicate and highly detailed. Over time her work evolved dramatically, and there was a boldness and strength to her paintings in her middle period. Her later paintings seemed to combine the two styles--they were bold, but also so extraordinarily detailed that it could take her years to finish one piece. She would use a brush with one hair for precision. I think they're amazing. I don't know what art critics today would think.

Did writing about real people made your work harder or easier?

It was both. It was easier because I didn't have to make up characters--I had to study them from all angles through the prism of their letters and their works and make them come alive as best I could. It was harder because I had a strong desire to honor Margery and Pamela by sticking to their real story as much as possible. I was very sensitive to this, and took out many passages where I had let my imagination work overtime. For instance, there were several times I wrote in fictional boyfriends for Pamela, thinking surely she had someone lurking about during the years of Diccon's [Richard Hughes] absence--but then I felt I was treading on shaky ground, and the scenes would feel false, and out they would go! But the temptation to let my imagination run wild was always there.

What are you working on now?

I do have a book I am working on, and the style bears absolutely no resemblance to The Velveteen Daughter. It is contemporary, a work of magical realism in which one of the main characters is a dog. What can I say? On the other hand, I've also been working on the plot of a novel set in New York City in the early 19th century. So we will see which one emerges first! --Jessica Howard, blogger at Quirky Bookworm

Laurel Davis Huber: Art and Legacy in Fiction

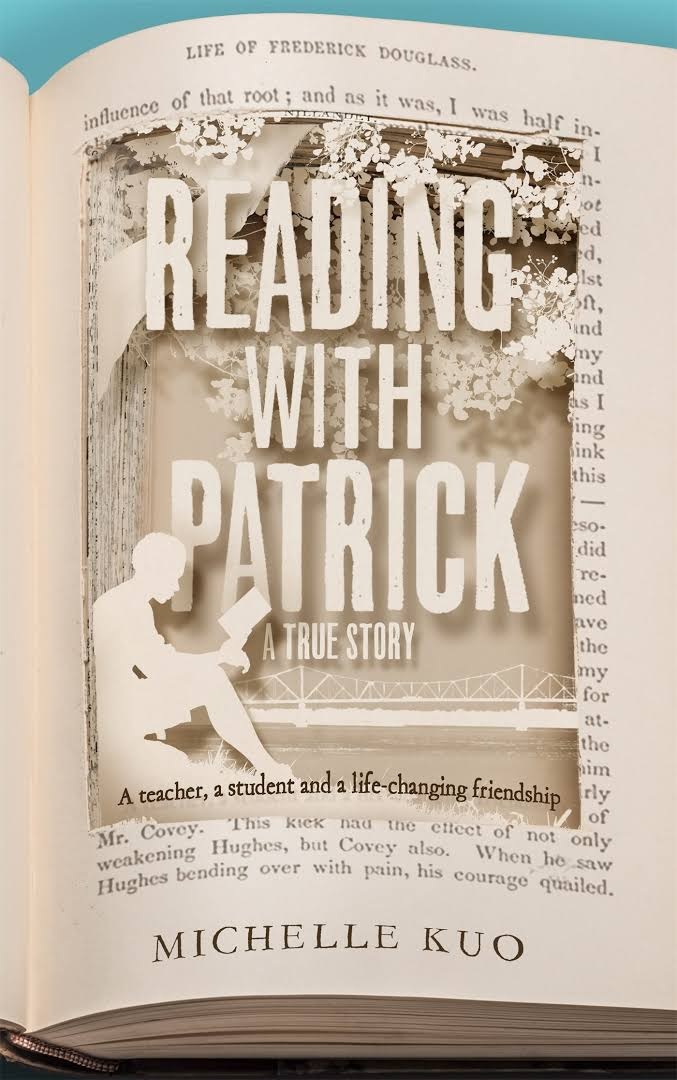

Still, the Delta was never far from Kuo's mind. And when she heard that Patrick had killed a man, she returned--and stayed, visiting him every day in the almost two years leading up to his trial. They read together and, ultimately, connected in a way Kuo had always hoped for, but feared was impossible: "There were moments when I was reading with Patrick that he appeared to me anew...." "[T]here seemed to exist between us a mystical and radical and improbable equality. This was what reading could do: It could make you, however fleetingly, unpredictable. You were not someone about whom another can say, You are this kind of person, but rather a person for whom nothing is predetermined." Ultimately, Kuo learned it is possible to change lives with words. Maybe not in the precise way one would expect or hope, but change nonetheless. --Stefanie Hargreaves, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Still, the Delta was never far from Kuo's mind. And when she heard that Patrick had killed a man, she returned--and stayed, visiting him every day in the almost two years leading up to his trial. They read together and, ultimately, connected in a way Kuo had always hoped for, but feared was impossible: "There were moments when I was reading with Patrick that he appeared to me anew...." "[T]here seemed to exist between us a mystical and radical and improbable equality. This was what reading could do: It could make you, however fleetingly, unpredictable. You were not someone about whom another can say, You are this kind of person, but rather a person for whom nothing is predetermined." Ultimately, Kuo learned it is possible to change lives with words. Maybe not in the precise way one would expect or hope, but change nonetheless. --Stefanie Hargreaves, editor, Shelf Awareness for Readers

Why do you think Pamela's fame didn't last? Perhaps her art didn't stand the test of time?

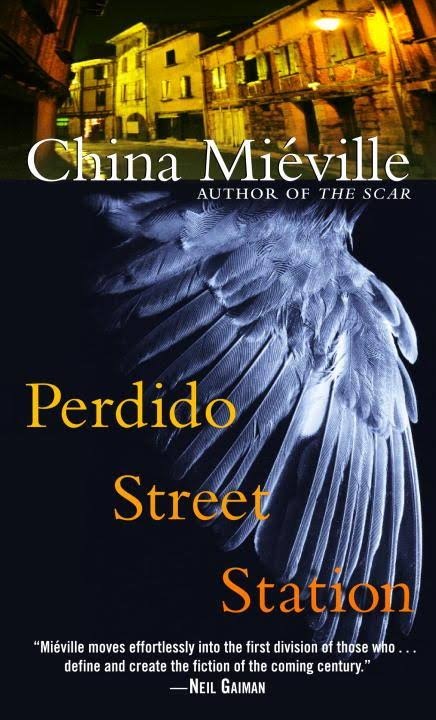

Why do you think Pamela's fame didn't last? Perhaps her art didn't stand the test of time? English author China Miéville is a man of many weird and wonderful talents. He is considered, along with Jeff VanderMeer, a principal participant in the New Weird movement, a loosely defined literary speculative fiction category with cross-genre fantasy, horror and sci-fi elements, sprinkled with deliberately unexplained mysteries and existential terror. Miéville is also an academic and political activist; he has a Ph.D. in international relations from the London School of Economics and is a champion of socialist causes (his doctoral theses, Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law, was published in 2005). His most recent book,

English author China Miéville is a man of many weird and wonderful talents. He is considered, along with Jeff VanderMeer, a principal participant in the New Weird movement, a loosely defined literary speculative fiction category with cross-genre fantasy, horror and sci-fi elements, sprinkled with deliberately unexplained mysteries and existential terror. Miéville is also an academic and political activist; he has a Ph.D. in international relations from the London School of Economics and is a champion of socialist causes (his doctoral theses, Equal Rights: A Marxist Theory of International Law, was published in 2005). His most recent book,