Good Cheer, Tasty Beer & Fine Reads

It all began last spring with Frances Stroh's intriguing Beer Money: A Memoir of Privilege and Loss. Since then, for some reason, good beer books have found their way to me, round after round.

Following a week in silent retreat at St. Joseph's Abbey in Spencer, Mass., I learned about Trappist Beer Travels: Inside the Breweries of the Monasteries by Caroline Wallace, Sarah Wood and Jessica Deahl. A combination journal, history and travelogue, the book offers an in-depth and entertaining look at legendary Trappist breweries worldwide, including St. Joseph's Abbey. (For the record, I consumed no ales while on the premises.)

Following a week in silent retreat at St. Joseph's Abbey in Spencer, Mass., I learned about Trappist Beer Travels: Inside the Breweries of the Monasteries by Caroline Wallace, Sarah Wood and Jessica Deahl. A combination journal, history and travelogue, the book offers an in-depth and entertaining look at legendary Trappist breweries worldwide, including St. Joseph's Abbey. (For the record, I consumed no ales while on the premises.)

In September, I heard Bill McKibben, author of the funny and timely novel Radio Free Vermont, tell an audience: "A Pollyanna I'm not, but two things that consistently cheer me up are 1) you can now get delicious bottled beer from almost every town in New England; and 2) somehow a lot of independent booksellers survived, in spite of everything that came at them." Locally-brewed beer not only drives the tale (Vermont is described as "beer-independent"), it's almost a character.

Then I read Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World by Johan Swinnen and Devin Briski, which nicely complements McKibben's independent streak ("Lagunitas' primary strategy is to donate its beer to local nonprofit organizations to sell as fundraisers") as well as Trappist legacy ("Prior to the twelfth century, monasteries were the only places that beer was brewed on anything close to a commercial scale"). This book teaches you more than you ever thought you needed to know about beer. It's, well, a refreshing read.

Then I read Beeronomics: How Beer Explains the World by Johan Swinnen and Devin Briski, which nicely complements McKibben's independent streak ("Lagunitas' primary strategy is to donate its beer to local nonprofit organizations to sell as fundraisers") as well as Trappist legacy ("Prior to the twelfth century, monasteries were the only places that beer was brewed on anything close to a commercial scale"). This book teaches you more than you ever thought you needed to know about beer. It's, well, a refreshing read.

With 2018 just around the corner, I'm thinking Graham Swift's pint-fueled novel Last Orders might have some words of wisdom to share: "And we all feel it, what with the sunshine and the beer inside us and the journey ahead.... Like we're off on a jaunt, a spree, and the world looks good, it looks like it's there just for us." Or maybe that's just the beer talking. --Robert Gray, contributing editor

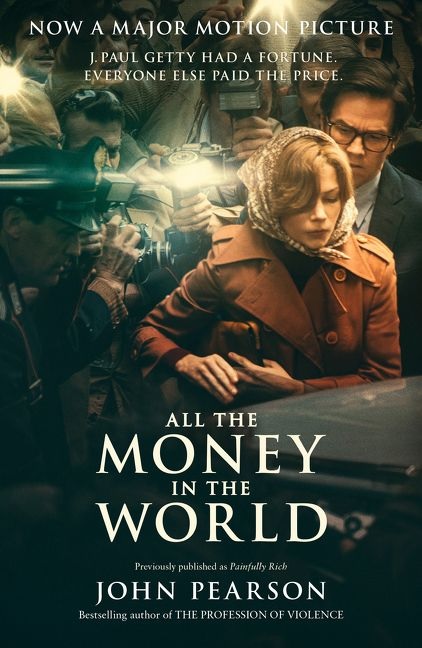

On July 10, 1973, 16-year-old John Paul Getty III, grandson of billionaire oil tycoon J. Paul Getty, was kidnapped in Rome. His abductors, the 'Ndrangheta organized crime group, demanded a $17 million ransom. John Paul Getty Jr. asked his father for the money, to which the infamously frugal patriarch replied that paying this ransom would endanger his 13 other grandchildren. In November, the kidnappers sent Getty III's severed ear to a local newspaper, threatening more mutilation if no money was forthcoming. J. Paul Getty finally conceded, to an extent: he negotiated a $2.9 million total ransom, paying $2.2 million himself--the largest tax-deductible amount--and lending the rest to John Paul Getty Jr. at a 4% interest rate. Getty III was released, several of the kidnappers arrested, but most of the money never recovered. The trauma of his captivity sent Getty III on a downward spiral of drug and alcohol abuse. In 1981, an overdose of Valium, methadone and alcohol caused a stroke that left him quadriplegic and partially blind. He died in 2011 at age 54.

On July 10, 1973, 16-year-old John Paul Getty III, grandson of billionaire oil tycoon J. Paul Getty, was kidnapped in Rome. His abductors, the 'Ndrangheta organized crime group, demanded a $17 million ransom. John Paul Getty Jr. asked his father for the money, to which the infamously frugal patriarch replied that paying this ransom would endanger his 13 other grandchildren. In November, the kidnappers sent Getty III's severed ear to a local newspaper, threatening more mutilation if no money was forthcoming. J. Paul Getty finally conceded, to an extent: he negotiated a $2.9 million total ransom, paying $2.2 million himself--the largest tax-deductible amount--and lending the rest to John Paul Getty Jr. at a 4% interest rate. Getty III was released, several of the kidnappers arrested, but most of the money never recovered. The trauma of his captivity sent Getty III on a downward spiral of drug and alcohol abuse. In 1981, an overdose of Valium, methadone and alcohol caused a stroke that left him quadriplegic and partially blind. He died in 2011 at age 54.