_Beowulf_Sheehan.jpg) |

| photo: Beowulf Sheehan |

Heather Abel has written for the New York Times, Slate, the Los Angeles Times and the online Paris Review. She worked as a reporter and editor for the San Francisco Bay Guardian and High Country News. Abel received an MFA in fiction writing from the New School University, and she's taught writing at the New School, UMass Amherst and Smith College. Her first novel, The Optimistic Decade (reviewed below), was just published by Algonquin. Raised in Santa Monica, Calif., Abel now lives in Northampton, Mass., with her husband and two daughters.

Your background parallels some characters in The Optimistic Decade. How much of the novel is based on your own life or people you know?

None of the characters are one-to-one based on anyone I knew. Instead, the characters each have aspects of my own personality. I grew up in an activist family, like Rebecca, though my parents were academics rather than journalists, like Ira. The milieu of radical leftist in L.A. was very familiar to me, and it was something I haven't seen much written about before.

In my early 20s, I moved to a small town in western Colorado to work for an environmental newspaper. The town itself was fascinating, with ranchers, coal miners, hippies who moved there in the '80s and this newspaper. I fell in love with the landscape--the mountains and high desert--and this place that felt like home. I was interested in all the different people there who felt a claim on this place. They all thought, "this mountain is my home," but they each had different ideas of what this home should look like. I loved that there was a sense of generosity, and we helped each other, even though we had different political ideas. It was the most politically diverse and interesting place I've ever lived. It gave me a sense of human possibility and community, even if I disagreed fundamentally with my neighbor.

Caleb and Ira have very different ideas about how to make a difference. Which approach resonates more with you?

I'm drawn to utopian communities, kibbutzes and communes. I've always been fascinated by this idea of creating the world you wish to see and living it out, but I'm also critical of that approach. I've read enough about them to know they usually fail and can get messed up by people's egos. So, I'm fascinated by them, but when I think of working politically, I think more about Ira's approach, trudging along and trying to make change in a community that already exists. Living in this imperfect world and trying to move it along every day is the approach that resonates with me most. But I'll always be interested in thinking of this idea of utopia because there is something so beautiful and magical about it.

There are some extremists in the novel, on both sides of the political spectrum. Did you intend to show parallels with today's politics?

When I lived in Colorado, I interacted with all kinds of people because I was a journalist in a small town that was very economically diverse. During the 2016 election, I heard a lot of the same words and phrases that I heard in the early '90s in Colorado. So, to me, there's a continuum between the people and the movements they talked about then and what we see happening now.

Ira explains the meaning of the title, The Optimistic Decade, at the end of the novel. Did you create this phrase?

Ira explains the meaning of the title, The Optimistic Decade, at the end of the novel. Did you create this phrase?

Early in writing the book, something happened politically in the real world. Though I don't usually hear my characters speaking to me, I was walking through New York, and I very clearly heard a voice say in my head, "Well, that's the end of the Optimistic Decade." I wrote it down, and I thought about it, and I knew I wanted that phrase in my novel, but I didn't yet know what it meant. I hadn't heard the phrase before, but it immediately resonated with me, referring not only to idealism and disillusionment but to these booms and busts in the West--how a town can be built up, with thousands of people moving there, and then decimated. So, it refers to the fluctuations both ways--politically and economically.

Did that phrase inspire the novel?

I was in the very beginning stages of working on the novel and didn't yet have an overall picture of what it was about. I wrote the phrase down and over time, it helped me understand what was tying everything together. I was in grad school then, and I asked a professor, "I want to write about these booms and busts in the West. I also want to write about what it was like to grow up so politically and with a sense of disillusionment. Which novel should I write?" And he said, "Don't hold anything back--write it all." This novel has many different parts in it, so that phrase helped me realize how things came together.

You've previously written nonfiction--articles, essays and a brief memoir. What made you decide to try fiction?

While I was a journalist, I went back to the West to report a story. The article was about who had access to the land. The rockhounds were hunting illegally for fossils, the recreationalists wanted to mountain bike, and there were miners, too. Who deserved access to the land? I realized I didn't want to write another straightforward journalistic piece about this. I wanted to get at something complicated and personal that I could only do through fiction, where I could be in each character's life for a little while.

How was the process of writing a novel different from writing nonfiction?

It was longer! And it was more magical. I loved living with these characters, and there was something truly comforting and magical and revelatory about it. I never write an essay if I can't learn something from it--there's always something that is puzzling me that I want to get at through the essay. With the novel, these were ideas I'd been wrestling with for most of my life. What does it mean to try to make change in the world? What does it mean to love a piece of land? Only by going through this weird process of making people up and making up a whole town could I answer these real questions.

In that way, it was stranger and more revelatory than writing nonfiction. That was the first thing my father said when he read this novel, "These are questions you've been asking since you were three! You would say, 'Why do we go to protests? What difference will it make?' " I was troubled by activism even though I was committed to it, even as a little kid. When my father first took me to the wilderness, I thought, "I love it here! I need to move here! I need to own this, be part of this!" Writing a novel is a very inefficient but amazing way of sorting through the questions in your life. --Suzan L. Jackson, freelance writer and author of Book By Book blog

Heather Abel: Activism, Growth and Disillusionment in the '90s

The "how" of vacationing is wittily explored in How Proust Can Change Your Life (Vintage, $16), a modern-day guidebook in which Proust's life and writings are the basis for advice on all matter of topics, including the risks of leaving home with the wrong expectations of travel.

The "how" of vacationing is wittily explored in How Proust Can Change Your Life (Vintage, $16), a modern-day guidebook in which Proust's life and writings are the basis for advice on all matter of topics, including the risks of leaving home with the wrong expectations of travel.  De Botton tackles the good, bad and ugly of globe-trotting in The Art of Travel (Vintage, $16.95), with truly hilarious insights into why the reality of travel is often so different from our expectations. Realizing the futility of expecting deliverance through travel, De Botton instead finds satisfaction in observing familiar surroundings with the attitude one would normally reserve for sight-seeing.

De Botton tackles the good, bad and ugly of globe-trotting in The Art of Travel (Vintage, $16.95), with truly hilarious insights into why the reality of travel is often so different from our expectations. Realizing the futility of expecting deliverance through travel, De Botton instead finds satisfaction in observing familiar surroundings with the attitude one would normally reserve for sight-seeing.  A Week at the Airport (Vintage, $17) offers up an unusual travel lens. De Botton spent a week inside Terminal 5 of London's Heathrow Airport as its writer-in-residence, observing and talking with travelers as they made their way through the vast glass and steel building. Most of us value punctuality when flying, but De Botton says he actually prefers it if his flight is delayed so he can spend more time at the airport!

A Week at the Airport (Vintage, $17) offers up an unusual travel lens. De Botton spent a week inside Terminal 5 of London's Heathrow Airport as its writer-in-residence, observing and talking with travelers as they made their way through the vast glass and steel building. Most of us value punctuality when flying, but De Botton says he actually prefers it if his flight is delayed so he can spend more time at the airport!

_Beowulf_Sheehan.jpg)

Ira explains the meaning of the title, The Optimistic Decade, at the end of the novel. Did you create this phrase?

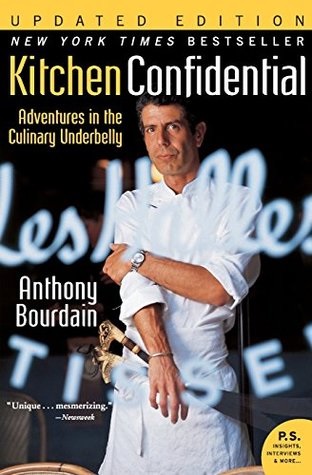

Ira explains the meaning of the title, The Optimistic Decade, at the end of the novel. Did you create this phrase? Culinary adventurer Anthony Bourdain's food travelogue Parts Unknown returned for its 11th season Sunday night on CNN. This is the itinerant gourmand's fourth such series, after the Travel Channel's No Reservations (2005–2012) and The Layover (2011–2013), and the Food Network's A Cook's Tour (2002-2003). Prior to TV stardom, Bourdain earned his chops as the bestselling author of Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly (Bloomsbury), his darkly funny memoir about life behind the stove. With scalding wit and honesty, he relates his road to becoming a chef and his hectic, often drug-fueled work in high-end New York City kitchens during the 1980s as well as shares inside restaurateur tips, like not to order fish on Monday (it's leftover from the weekend) and never order steak well done (overcooking masks low-quality cuts).

Culinary adventurer Anthony Bourdain's food travelogue Parts Unknown returned for its 11th season Sunday night on CNN. This is the itinerant gourmand's fourth such series, after the Travel Channel's No Reservations (2005–2012) and The Layover (2011–2013), and the Food Network's A Cook's Tour (2002-2003). Prior to TV stardom, Bourdain earned his chops as the bestselling author of Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly (Bloomsbury), his darkly funny memoir about life behind the stove. With scalding wit and honesty, he relates his road to becoming a chef and his hectic, often drug-fueled work in high-end New York City kitchens during the 1980s as well as shares inside restaurateur tips, like not to order fish on Monday (it's leftover from the weekend) and never order steak well done (overcooking masks low-quality cuts).