|

| photo: Christine Beane |

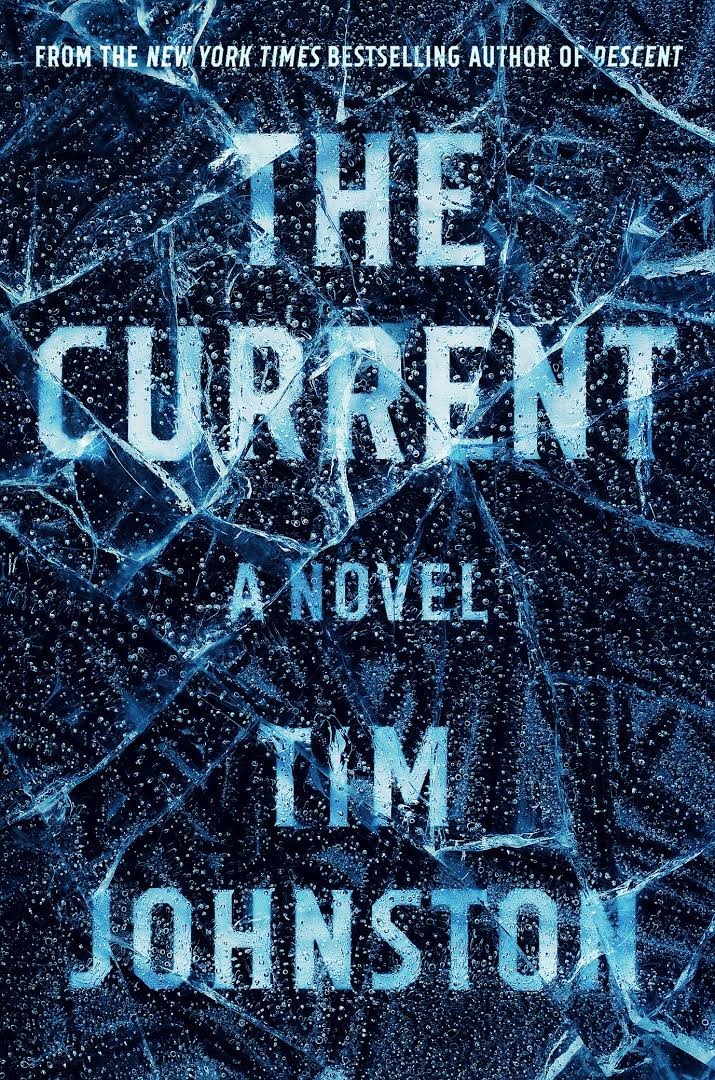

Tim Johnston is the author of the story collection Irish Girl, which won the O. Henry Prize and other awards, and the novels Descent and Never So Green. His new novel is The Current (Algonquin, 27.95), about two teenage girls whose car crashes into an icy Minnesota river; only one survives. The circumstances surrounding the crash are murky, and the incident might be related to another death in the river a decade earlier. Johnston, who lives in Iowa, discusses writing and how nature inspires his stories.

In your books, nature is almost a living character--the Rockies in Descent and the river in The Current. Other than nature being a formidable opponent, why do you like incorporating it into your stories?

In Descent, it was actually the Rockies that inspired the story. I was working as a carpenter up there when I began to write about the Courtland family, and it's the Rockies that draw them so far from home. But when their daughter does not return from a run up the mountain, their awe turns to something else entirely as they wait--and wait--to see if she will ever come down again. What begins as setting becomes essential to plot and theme--and to the title itself.

Likewise, when I began The Current, I didn't know how essential the river would become to the story, other than as the locale of the drowning of two young women, 10 years apart. But as I got deeper into the lives of the survivors of those two tragedies, the river became a bridge across time--or through time; it freezes and thaws and flows and freezes again, but it never stops reminding them of what connects them, and what they've lost. They are all in the same current.

You place readers in the environment with incisive details. How much research do you do on the places you write about?

Living in the Rocky Mountains was my research for Descent, and I used the names of local landmarks and streets--only to be told later, by readers familiar with the area, how wrong I'd gotten it all. So when I began The Current, I knew that the small town in which the novel is set, including the river, would be entirely fictional. Of course, as an Iowan, it's not a great stretch to imagine a small town in Minnesota in the dead of winter. I just pushed it all north for a colder, stranger sense of place and people.

Your novels have a recurring theme of lost or missing children. What draws you to explore that particular kind of grief?

In just this last year in Iowa, two college women--one on a golf course and the other out for a run in her hometown--met a terrible fate. The TV shows us the happy smiling photos of the young women, and the living tortured faces of their parents. It is truly horrible and I cannot understand it, not really; no one who hasn't gone through it can. And maybe that's what draws me to it as a writer--how familiar the story becomes to us over time, yet how singular and excruciating it must be for those who go through it. I wonder, too, if having no children of my own allows me to explore a kind of terror and grief I might not be able to if I had to imagine my own child as the victim.

When you were a kid, you wrote comic books. Would you return to that?

When you were a kid, you wrote comic books. Would you return to that?

Comic books are a gateway drug to becoming a reader, which is the gateway drug to becoming a writer. But for me, as a kid, it was all about the artwork. I spent much of my childhood hunched over drawing pads, and I got pretty darn good. I entered college as an art major but by the end of my first year, I'd switched to English because I wanted to read books. From there I found my way into creative writing, and suddenly that part of my life--that kid hunched over drawing pads--was over. Although I think I'm still pretty much that same kid, it's just a different kind of hunching.

You've worked as a carpenter while writing. Are there similarities between the two crafts?

Well, there's turning raw materials into something lasting and beautiful. There's having good sharp tools and knowing how to use them. But none of that happens without years of learning the craft, of actually banging away in the woodshop. Of honing whatever gifts or drive you have under the influence of greater craftsmen than you. You need time to develop your eye for detail, and you must have the patience to attend to every one of those details as if nothing is more important. In carpentry, this will drive your employer crazy, if he is your father and he's paying you by the hour. As a writer, there is--or should be--as Yoda might say, no rush, only patience.

David Sedaris gave you a big bump in visibility when he promoted your story collection, Irish Girl, on his tour. Now that you're an established author, whose book(s) would you like to mention here?

Pilot by PD Mallamo. He is the most exciting and original writer I've read in years, and this is his first book. (Full disclosure: I wrote the foreword.) --Elyse Dinh-McCrillis, blogger at Pop Culture Nerd

Tim Johnston: Building Stories

As a newcomer to the U.S. several decades ago, I made my first foray into American literature with Edith Wharton's Custom of the Country (Vintage, $12), and soon I was devouring everything this fine lady had written. This week, as we celebrate what would have been Wharton's 156th birthday, it's an opportune time to highlight some of her most impactful work.

As a newcomer to the U.S. several decades ago, I made my first foray into American literature with Edith Wharton's Custom of the Country (Vintage, $12), and soon I was devouring everything this fine lady had written. This week, as we celebrate what would have been Wharton's 156th birthday, it's an opportune time to highlight some of her most impactful work. Wharton's true genius lay in her keen social commentary and comically ironic observations that still resonate with readers more than a century later. In her Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, The Age of Innocence (Modern Library, $11), she explores the dilemma of a morally superior New York lawyer engaged to a dull, pretty girl who finds himself passionately in love with his fiancé's scandal-prone cousin, a divorced countess.

Wharton's true genius lay in her keen social commentary and comically ironic observations that still resonate with readers more than a century later. In her Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, The Age of Innocence (Modern Library, $11), she explores the dilemma of a morally superior New York lawyer engaged to a dull, pretty girl who finds himself passionately in love with his fiancé's scandal-prone cousin, a divorced countess. To Wharton, every society was its own ecosystem, with flaws and petty grievances and nostalgia for the past. Old New York (Scribner, $17) is a collection of novellas, each based in a different decade from 1840 to 1870, in which she boldly addresses subjects that polite society refused to contemplate, like infidelity and illegitimacy.

To Wharton, every society was its own ecosystem, with flaws and petty grievances and nostalgia for the past. Old New York (Scribner, $17) is a collection of novellas, each based in a different decade from 1840 to 1870, in which she boldly addresses subjects that polite society refused to contemplate, like infidelity and illegitimacy. In addition to her writing, Wharton was known for her tasteful interior decorating; she paved the way for a more exuberant approach by rejecting the overly fussy and frumpy Victorian-era design of the time. The Decoration of Houses (Norton, $25) features her fresh new ideas for every part of the house--including rooms that most of us don't have to worry about anymore such as ballrooms, galleries and saloons.

In addition to her writing, Wharton was known for her tasteful interior decorating; she paved the way for a more exuberant approach by rejecting the overly fussy and frumpy Victorian-era design of the time. The Decoration of Houses (Norton, $25) features her fresh new ideas for every part of the house--including rooms that most of us don't have to worry about anymore such as ballrooms, galleries and saloons.

When you were a kid, you wrote comic books. Would you return to that?

When you were a kid, you wrote comic books. Would you return to that?