|

| photo: Scott Swann |

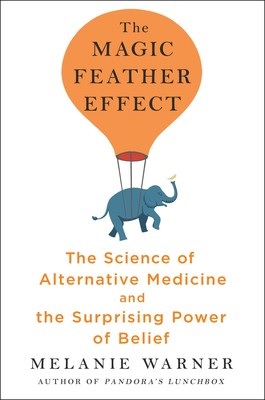

Melanie Warner follows her well-researched look at processed food in the United States, Pandora's Lunchbox, with a deep dive into the field of alternative medicine. In The Magic Feather Effect: The Science of Alternative Medicine and the Surprising Power of Belief (Scribner, $27), she visits acupuncturists, chiropractors, energy healers and other practitioners of alternative medicine and experiences their therapies firsthand. What she learns is eye-opening: the power of belief might be even more effective than most people think.

How would you characterize your feelings about alternative medicine before writing The Magic Feather Effect?

Unlike many people, who come to this topic either as advocates or skeptics, I started somewhere in the ambivalent middle. Years earlier, I had received a few acupuncture sessions from a friend and, in a school auction, won a "bodywork session" that turned out to be cranial-sacral massage, but neither experience was particularly memorable. I was also mildly skeptical about the theories behind alternative practices--the profound and undetected (by modern science) forces like qi, or subtle energy operating in the body and affecting one's health. Still, I had a genuine curiosity and wondered about different healing claims I was hearing. Even some skeptics have acknowledged the activity of placebo effects in alternative medicine. I wanted to know whether this was real and what the potential of these practices might be.

Did your feelings change after writing the book?

I think I became more skeptical of healing claims. As I went on in my research, it became clearer what types of health conditions alternative medicine could potentially be helpful for and which ones it's probably not going to change very much (although people could still see improvements in mood, outlook and symptoms like pain and fatigue that accompany some diseases). I think many forms of alternative medicine can provide people with value, especially when delivered by people who have real talent as healers--skills we're not quite sure how to appreciate or even categorize these days. But in order for alternative medicine and placebo effects or what you might call mindset-based healing (which are not 100% the same, but pretty close) to be appreciated, I think we need to first understand the limitations.

Would you say that the placebo is a useful tool for licensed medical doctors as well as alternative medicine practitioners?

Absolutely. If placebo effects are improvements in symptoms caused by the positive social context in which a treatment is delivered, then any treatment has the potential to elicit these effects. Since medical doctors are our most trusted sources of healing, our belief in them can create powerful placebo effects. The challenge is how to overcome inherent challenges to using placebo effects in a medical setting. It's not ethical for doctors to give people fake pills, nor is it acceptable for patients to get sham surgery, even though some people with certain conditions will be helped tremendously by it. You could, however, go the route of honestly informing patients that you're giving them a placebo and that placebos have been shown to produce potent mind-body effects in some patients. Recent studies have shown that, amazingly, this kind of transparency doesn't ruin the effect.

What was it like to subject yourself to some of these alternative health practices? Was it unnerving? Amusing? Something else?

What was it like to subject yourself to some of these alternative health practices? Was it unnerving? Amusing? Something else?

Most of all, they were relaxing. Many were new to me so I had to kind of surrender and see what would happen. Nothing dramatic occurred, but it felt simultaneously calming and enlivening to have someone who believes wholeheartedly in a particular practice focus all their attention and intentions on you. In my Reiki session, I got into a perceptually hazy state where sensations from the healer's hands seemed very intense. For the most part, I took all these treatments seriously. The only one I found incredibly amusing was an instance in which the practitioner kept "asking" my body questions like whether I had any childhood trauma or if the water I was drinking had troubling contaminants in it.

Your book taught me new things about pain--what experts know and don't know about it, and how it manifests in the body. For instance, a patient's personal understanding of "safety" can affect how they feel pain in a given moment.

When we feel pain, whether acute from some injury or chronic from a whole variety of possible causes, we intuitively assume it's coming from the body region that hurts. But this, it turns out, isn't really the case. Over the last few decades, scientists have begun to understand how pain is a protective sensation created by our brains to keep us from harm. While nerve signals from the body are an important part of the equation--they shoot up to inform the brain about what's happening--pain itself is a multifaceted, involuntary decision made in the brain, and thus can be modulated, temporarily blocked and even eradicated by mindsets. Researchers are trying to work out all the particular regions and circuits involved, but like so many things with the human brain, it's immensely complex. There's still much more to be learned in this area.

Your book also points out that some world-class medical institutions, like the Cleveland Clinic, now offer alternative medicine as part of their treatment offerings. Do you see this as a trend? Will more mainstream medical doctors and institutions begin to recommend alternative medicine to patients?

Major medical facilities have "integrative" medicine centers largely because an increasing number of people want to use alternative or mind-body approaches. I think we will cease to think of these as "alternative" and simply as "medicine" only when large, rigorous clinical trials show they have meaningful effects for specific conditions beyond the placebo version (if it exists) or beyond the usual care people are getting. To some extent, acupuncture, chiropractic and tai chi already have such studies. Mechanistic research also needs to show a plausible theory for how these practices work. In some ways, this is a higher standard than some current medical treatments have had to meet, but such is the price outsiders sometimes have to pay to gain entry into the system. --Amy Brady, freelance writer and editor

Melanie Warner: Exploring the Power of Belief

I grew up reading books with strong female protagonists, books such as Catherine, Called Birdy by Karen Cushman (Clarion, $7.99) and The Blue Sword by Robin McKinley (Puffin, $8.99). So it's always surprising and a little dispiriting to me when a parent or grandparent at the bookstore asks for recommendations for a boy with the proviso that "he doesn't like reading about girls." At least half of the books I intended to hand them are immediately out of the running, including a number of classics. The reverse--girls who will only read books about girls--comes up much less frequently, in my experience.

I grew up reading books with strong female protagonists, books such as Catherine, Called Birdy by Karen Cushman (Clarion, $7.99) and The Blue Sword by Robin McKinley (Puffin, $8.99). So it's always surprising and a little dispiriting to me when a parent or grandparent at the bookstore asks for recommendations for a boy with the proviso that "he doesn't like reading about girls." At least half of the books I intended to hand them are immediately out of the running, including a number of classics. The reverse--girls who will only read books about girls--comes up much less frequently, in my experience. For all the older relatives who tell me their boys want books about boys, this rarely seems to be a problem when I'm recommending books directly to the child. It doesn't hurt that we live in a golden age of badass women, from Sarah J. Maas's more traditionally deadly women in the Throne of Glass (Bloomsbury, $11.99) series to the brave protagonist of Angie Thomas's The Hate U Give (Balzer & Bray, $18.99). I think it's easy to forget how open-minded children can be, given the opportunity. They want escapism--they want to be put in other kids' shoes.

For all the older relatives who tell me their boys want books about boys, this rarely seems to be a problem when I'm recommending books directly to the child. It doesn't hurt that we live in a golden age of badass women, from Sarah J. Maas's more traditionally deadly women in the Throne of Glass (Bloomsbury, $11.99) series to the brave protagonist of Angie Thomas's The Hate U Give (Balzer & Bray, $18.99). I think it's easy to forget how open-minded children can be, given the opportunity. They want escapism--they want to be put in other kids' shoes. One of my most consistently successful recommendations for children of any age or gender is the comic book series Lumberjanes (Boom Box, $14.99). The feminist twist inherent in the title might alert some parents, but the fictional camp for "Hardcore Lady Types" is never anything approaching preachy. It's hilarious and fun, drawing on the universal desire to see a bunch of kids battle supernatural creatures with clever quips at the ready. Underneath these surface pleasures, Lumberjanes is remarkably perceptive about young people's doubts and insecurities, and far more engaging than anything involving, for example, a boy super-spy.

One of my most consistently successful recommendations for children of any age or gender is the comic book series Lumberjanes (Boom Box, $14.99). The feminist twist inherent in the title might alert some parents, but the fictional camp for "Hardcore Lady Types" is never anything approaching preachy. It's hilarious and fun, drawing on the universal desire to see a bunch of kids battle supernatural creatures with clever quips at the ready. Underneath these surface pleasures, Lumberjanes is remarkably perceptive about young people's doubts and insecurities, and far more engaging than anything involving, for example, a boy super-spy.

What was it like to subject yourself to some of these alternative health practices? Was it unnerving? Amusing? Something else?

What was it like to subject yourself to some of these alternative health practices? Was it unnerving? Amusing? Something else? Russell Baker, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and long-time New York Times columnist, died January 21 at age 93. After an early career that included stints as a police reporter, rewrite man and London correspondent for the Baltimore Sun, and Washington correspondent for the Times, Baker became a columnist in 1962. He wrote nearly 5,000 "Observer" commentaries before his retirement in 1998. Baker's irreverent musings earned the 1979 Pulitzer for distinguished commentary.

Russell Baker, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and long-time New York Times columnist, died January 21 at age 93. After an early career that included stints as a police reporter, rewrite man and London correspondent for the Baltimore Sun, and Washington correspondent for the Times, Baker became a columnist in 1962. He wrote nearly 5,000 "Observer" commentaries before his retirement in 1998. Baker's irreverent musings earned the 1979 Pulitzer for distinguished commentary.