|

| photo: Patricia Williams |

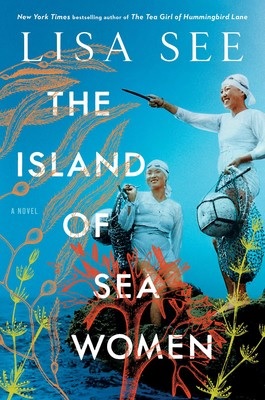

Lisa See is the author of six historical novels (including The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane), a mystery series set in modern-day China and On Gold Mountain, a memoir of her Chinese-American family's history. Her newest novel, The Island of Sea Women (Scribner, $27; reviewed below), explores the long tradition of haenyeo, female deep-sea divers, on the Korean island of Jeju.

Tell us about the inspiration for The Island of Sea Women.

About 10 years ago, I was waiting at the doctor's office, leafing through some magazines. There was a tiny article, maybe a paragraph or two and a photo, about the haenyeo culture. I ripped it out and took it home. I was finishing up a book at the time, and I had another two books to write, but any time I saw something about the haenyeo, I would cut it out and save it.

I was captivated by this culture of women divers for several reasons: it was a matrifocal society. They had the greatest ability of all human beings on earth to withstand cold water. The community of the divers and the way they worked together was so strong. Then I started to learn more about Jeju itself and its history, and I was fascinated. I didn't know, for example, that Korea was a Japanese colony. I learned about the Japanese presence on Jeju during World War II: many people believed that when the tide of the war changed, the Allies would go through Jeju to get to Japan. All of that was just fascinating.

For your research into the haenyeo culture, did you travel to Jeju?

Yes. I got to stay in three different areas of the island, and near one of them, there was a beach where several retired haenyeo would spend time. The woman who was my translator is the daughter of a haenyeo. She has a Ph.D. in English literature, and I interviewed her mother, whose name is Young-sook (like my protagonist). Some of what happens in my book, with Young-sook's daughter winning an academic contest and going off to school in the city, actually happened to this family.

When I was interviewing the haenyeo, especially the older ones, it struck me that they all wanted to talk about their kids. They had large families (there was no birth control), and they'd have six to eight children. These days, they were all out in the world doing different jobs: a makeup artist, a sound engineer, a lawyer, a doctor. All of them were looking outward, and had moved away from the farm life and agricultural traditions of Jeju. But their mothers were so proud.

The haenyeo have a long history on Jeju. Why did you choose this particular period (the 1930s to the present day) to explore?

This period is a time of such political transition for the country, but also in terms of technology--electricity and indoor plumbing--and of access to the outside world. That changed everyone's lives: not only the lives of the haenyeo, but their families and their communities. I wanted to explore the effects of all those changes.

Many World War II stories published in the West focus on France, Britain, the U.S. "home front" or even Japan. Why do you think that is, and why did you choose to explore the war's impact on a lesser-known location and its people?

Many World War II stories published in the West focus on France, Britain, the U.S. "home front" or even Japan. Why do you think that is, and why did you choose to explore the war's impact on a lesser-known location and its people?

I think there are a couple of reasons for that. Our country has always looked back toward Europe: the U.S. is still pretty Eurocentric. And I don't want to diminish the severity of what happened in Europe during the war. But I also think the Pacific in general was so foreign to most Americans at that time. All those countries were still unfamiliar. Think about Chinese immigration: people came over during the Gold Rush, and then to help build the transcontinental railroad. Then we had the Chinese Exclusion Act, which lasted until 1943. These countries had tiny populations in the U.S., compared to immigrant populations from Europe. What happened in the Pacific theater, and later in Korea, continues to play a role in our international relations today. It's not history that we know very well, and yet it has had an effect. North and South Korea are so much in our news, and it's interesting to think about how the division came to be.

The culture of Jeju and the haenyeo is shaped and dominated in some ways (though not all) by women. Can you talk a bit about this matrifocal culture?

Korea is the most Confucian of all the Asian countries, and so for this island to be in such opposition to that is really interesting. Confucius had a lot of thoughts about women, and none of them were good. That has a huge effect on the culture of Korea across the board. The haenyeo stood in contrast to that, but even while they were flourishing, they never had entire control. There were questions and contradictions: yes, women are in charge, but are they? Only sons can perform ancestor worship, for example, and men still exclusively make some of the decisions. So it was always a somewhat conflicted situation.

Forgiveness is a huge theme in the novel: Young-sook, the narrator, struggles to forgive her friend Mi-ja. The people of Jeju and Korea must also come to terms with great loss and pain.

I knew that I wanted to have this break between friends. This is fascinating to me personally: how we tell friends things we wouldn't tell our parents or partners or children. It's a very particular kind of intimacy, and it can also leave you open to betrayal. I wanted to write about that, but also to have this larger historical event on Jeju where people either rise to the occasion or they fail. Since then, Jeju has actually claimed its identity and even marketed itself as an island of forgiveness. So I wanted to use the incidents that sparked the idea of Jeju as a place of forgiveness.

I also wanted to explore the ideas of blame and guilt: you can blame somebody for their actions, but you can also feel guilty for what you've done. Early on in my research, I read an article about a village on Jeju that split after the anti-communist massacre in 1949. It became two villages, and they took two different names. And all these years later, they decided to forgive each other, and go back to being one village. We have so many conflicts around the world that last a long time. I thought there was a lot here to explore and learn about forgiveness. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

Lisa See: A Deep Dive into Forgiveness

Spy fiction has many modes and guises, encompassing superspies like James Bond and more grounded characters like George Smiley. The tone often depends on how frankly the author wishes to engage with espionage's checkered history. For a not-so-brief primer on the CIA, I recommend Tim Weiner's excellent Legacy of Ashes (Anchor, $18.99). The title makes his perspective clear, but he backs up his laundry list of global misdeeds with mountains of evidence.

Spy fiction has many modes and guises, encompassing superspies like James Bond and more grounded characters like George Smiley. The tone often depends on how frankly the author wishes to engage with espionage's checkered history. For a not-so-brief primer on the CIA, I recommend Tim Weiner's excellent Legacy of Ashes (Anchor, $18.99). The title makes his perspective clear, but he backs up his laundry list of global misdeeds with mountains of evidence. Graham Greene proved that spy fiction could be gripping and politically aware in 1955 with his classic The Quiet American (Penguin, $17). The novel takes place in the waning days of French colonialism in Vietnam, using the idealistic CIA agent Alden Pyle as a window into the United States' growing involvement. Greene's novel is a cogent and sadly prescient critique of American foreign policy, showing how the best intentions can go terribly awry.

Graham Greene proved that spy fiction could be gripping and politically aware in 1955 with his classic The Quiet American (Penguin, $17). The novel takes place in the waning days of French colonialism in Vietnam, using the idealistic CIA agent Alden Pyle as a window into the United States' growing involvement. Greene's novel is a cogent and sadly prescient critique of American foreign policy, showing how the best intentions can go terribly awry. Two more recent books have offered similarly scathing critiques of Western spycraft. In Lauren Wilkinson's American Spy (Random House, $27), the mission of the protagonist--a young black woman--is to get close to the real-life revolutionary and president of Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara, who introduces her to the terrible compromises that often marked the United States' Cold War policies. Louise Doughty's Black Water (Picador, $16) is set in Indonesia in 1998 and follows a member of a shadowy international organization as he waits for his sins to catch up to him. These sins are described in flashbacks to 1965, when an attempted coup and subsequent anti-Communist purge left as many as a million Indonesians dead. The military leader who oversaw the coup was U.S.-supported, and intelligence services like the protagonist's organization played a role in abetting the massacre. The protagonist's feelings of guilt may in some sense stand in for our own, as readers are forced to contemplate what was done in the name of fighting Communism. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Two more recent books have offered similarly scathing critiques of Western spycraft. In Lauren Wilkinson's American Spy (Random House, $27), the mission of the protagonist--a young black woman--is to get close to the real-life revolutionary and president of Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara, who introduces her to the terrible compromises that often marked the United States' Cold War policies. Louise Doughty's Black Water (Picador, $16) is set in Indonesia in 1998 and follows a member of a shadowy international organization as he waits for his sins to catch up to him. These sins are described in flashbacks to 1965, when an attempted coup and subsequent anti-Communist purge left as many as a million Indonesians dead. The military leader who oversaw the coup was U.S.-supported, and intelligence services like the protagonist's organization played a role in abetting the massacre. The protagonist's feelings of guilt may in some sense stand in for our own, as readers are forced to contemplate what was done in the name of fighting Communism. --Hank Stephenson, bookseller, Flyleaf Books, Chapel Hill, N.C.

Many World War II stories published in the West focus on France, Britain, the U.S. "home front" or even Japan. Why do you think that is, and why did you choose to explore the war's impact on a lesser-known location and its people?

Many World War II stories published in the West focus on France, Britain, the U.S. "home front" or even Japan. Why do you think that is, and why did you choose to explore the war's impact on a lesser-known location and its people? W.S. Merwin, U.S. poet laureate from 2010 to 2011 and winner of two Pulitzer Prizes, died last week at age 91. He lived in rural Maui for many years, where he transformed a former pineapple plantation into a sanctuary for rare palm trees. Much of his work reflected his commitment to conservation and Buddhist philosophy. In addition to his two Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry (1971 and 2009), Merwin won the National Book Award, the Tanning Prize from the Academy of American Poets, the Bollingen Prize for Poetry, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Writers' Award, the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize from the Poetry Foundation and the PEN Translation Prize.

W.S. Merwin, U.S. poet laureate from 2010 to 2011 and winner of two Pulitzer Prizes, died last week at age 91. He lived in rural Maui for many years, where he transformed a former pineapple plantation into a sanctuary for rare palm trees. Much of his work reflected his commitment to conservation and Buddhist philosophy. In addition to his two Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry (1971 and 2009), Merwin won the National Book Award, the Tanning Prize from the Academy of American Poets, the Bollingen Prize for Poetry, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Writers' Award, the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize from the Poetry Foundation and the PEN Translation Prize.