|

| photo: Karen Osborne |

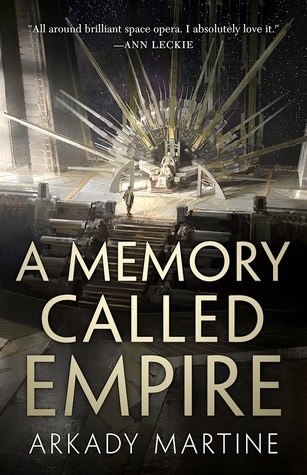

Arkady Martine makes use of her knowledge as a historian of the Byzantine Empire in her debut novel, A Memory Called Empire (reviewed below), out now from Tor Books. Martine lives in Baltimore, Md., with her family.

A Memory Called Empire melds plot elements that include a murder mystery, political machinations and science fiction space opera. Can you tell us a bit about what inspired this plot combination?

The plot structure of this book is heavily inspired by classic spy novels. I read a lot of John le Carré, and what I adore about his work is both the intense internality of a protagonist engaged in spycraft--how they have to think about what they're doing from multiple, mutually contradictory angles, all the time--and also how there's usually an inciting incident which drops the protagonist into a political conflict they aren't prepared for. The murder mystery is a great inciting incident: someone is dead, we don't know why, the protagonist needs to figure it out. In a spycraft-based novel, the murder victim usually has information the protagonist really needs, and now they have to work to get it some other way--which also helps kickstart their involvement in the politics. So for me murder mysteries and political thrillers are very close friends, plotwise. Space opera's another thing... sort of.

I'm a huge Star Wars fan, and a huge Frank Herbert fan, in the sense that I love enormous, sprawling, politically rich and visually lush space-based universes that don't have much connection to Earth now... except thematically. Also, science fiction is the genre of my heart--it's what gets me excited, it gives me the freedom to ask big questions from sideways angles, like, "what happens during conditions of cultural imperialism," or "how do we honor the memory of our ancestors, but with unusual, out-of-everyday-scale intensifiers." Cultural imperialism created by wormhole travel mechanics! Ancestral memory that can actually be transmitted person to person! Big questions, weird angles.

And space opera's no stranger to the political thriller or the murder mystery. I am in no way the first person on this ground: Frank Herbert's Dune, as I said above, but also C.J. Cherryh's work--Cyteen especially is a good comparison, since it's also a murder mystery with political consequences, using space opera technology to make the questions it asks much more focused, pointed and strange. And more recently, books like Mur Lafferty's Six Wakes, which is a literal murder mystery in space, or Ann Leckie's Ancillary Justice, which is a political thriller in space... there are a lot of us out here. It's a good place to be.

The world-building in the novel is both complex and vivid. Did it come to you fully formed, or piece by piece?

The world-building in the novel is both complex and vivid. Did it come to you fully formed, or piece by piece?

The Teixcalaanli empire is what happened when I put Byzantium, the Mexica and the Mongol Empire in a blender; it is a culturally imperialistic universalizing empire that thinks it is the only real civilization in the universe. And Lsel Station comes from my forever-long obsession with generation ships and cultural transformation in closed societies. (Blame Poul Anderson's Tau Zero for that one, though the best modern examples for me are Elizabeth Bear's Jacob's Ladder trilogy and Rivers Solomon's An Unkindness of Ghosts.) Which is all an elaborate way of saying that I built almost everything in this novel piecemeal: a lot of it came from having a defined aesthetic that I wanted to hit and going looking for what fit that aesthetic. I'm not someone who plans much in advance, in terms of writing things down; I find them when I need them, and the work I do beforehand is just developing for myself a sense of what feels right and what doesn't, for the culture I'm creating.

And how did you go about keeping track of all the moving parts? It had to be tricky, considering how complex the world of the Empire is.

I definitely should have started keeping track earlier than I did! This might have saved me the part where I had to, on edit round #2, write down what everyone's motivations and goals really were. I also keep a list of names: people, places, ships, literary works, etc., which is like a reference bible. A really bad reference bible, as it hasn't got much else but that list in it. I've also got some sketch maps of places that have particular pathways or geometries that I needed to be able to reproduce accurately several times in the book. My wife, Viv, who is a much better artist than I'll ever be, drew Lsel Station as seen from space, which was incredibly helpful.

But mostly I write in a kind of organic-fractal manner, where I have an end goal, and some ideas of what each character wants in a scene, and what the scene needs to accomplish to move towards that goal--and then I improvise. I get better results that way; I can surprise myself, and the relationships between characters are less sterile and designed.

In addition to being an author, you're a historian of the Byzantine Empire and a city planner. How did these influence A Memory Called Empire?

The book is, in a lot of ways, the fictional version of what I did in my post-doctoral project in Byzantine history of imperialism. Here's the short version: in the year 1044 AD, the Byzantine Empire annexed the small Armenian kingdom of Ani. The empire was able to do this for a lot of reasons--political, historical, military--but the precipitating incident involved the Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church, a man named Petros Getadarj, who was determined to prevent the forced conversion of the Armenians to the Byzantine form of Christianity. He did this by trading the physical sovereignty of Ani to the Byzantine emperor in exchange for promises of spiritual sovereignty. When I started writing this book, my inciting question was: What's it like to be that guy? To betray your culture's freedom in order to save your culture?

So I ended up writing a book about the seduction of empire, the problems of linking up identity with memory and how to use an oration contest to start a riot. As for my city planning job, the entire subplot (about the subway and algorithms) is straight out of a "smart cities" course, and how I have been thinking about the way cities see, or don't see, the people who live in them. --Lois Faye Dyer, writer and reviewer

Arkady Martine: Political Intrigue and Murder--in Space

Vicky Chen is a teenage reader, aspiring author and book blogger. You can find her talking about books on her blog, on Twitter and on Instagram.

Vicky Chen is a teenage reader, aspiring author and book blogger. You can find her talking about books on her blog, on Twitter and on Instagram. Looking at representation in YA over the past few years reveals how diversity in authorship and within books has increased, thanks to organizations like We Need Diverse Books. Books and authorship are now more varied in ways other than race, and characters and topics have expanded beyond the subset of just being "diverse." While these books let teens see themselves represented in literature, the inclusion of tropes lets teens see themselves as part of literature.

Looking at representation in YA over the past few years reveals how diversity in authorship and within books has increased, thanks to organizations like We Need Diverse Books. Books and authorship are now more varied in ways other than race, and characters and topics have expanded beyond the subset of just being "diverse." While these books let teens see themselves represented in literature, the inclusion of tropes lets teens see themselves as part of literature. Diverse books that feature tropes show that diversity isn't "just a trend" because they're not segregated to a "diverse book" category--they're integrated by subject and content. To All the Boys I've Loved Before by Jenny Han uses the "fake dating trope"; Pride by Ibi Zoboi places a fresh and much-needed spin on Pride and Prejudice; and They Both Die at the End by Adam Silvera takes the "24-hour novel" concept and makes it even more intense. These books are here to stay, their representation and tropes combined allowing teens to see themselves as part of literature and part of a community.

Diverse books that feature tropes show that diversity isn't "just a trend" because they're not segregated to a "diverse book" category--they're integrated by subject and content. To All the Boys I've Loved Before by Jenny Han uses the "fake dating trope"; Pride by Ibi Zoboi places a fresh and much-needed spin on Pride and Prejudice; and They Both Die at the End by Adam Silvera takes the "24-hour novel" concept and makes it even more intense. These books are here to stay, their representation and tropes combined allowing teens to see themselves as part of literature and part of a community.

The world-building in the novel is both complex and vivid. Did it come to you fully formed, or piece by piece?

The world-building in the novel is both complex and vivid. Did it come to you fully formed, or piece by piece?