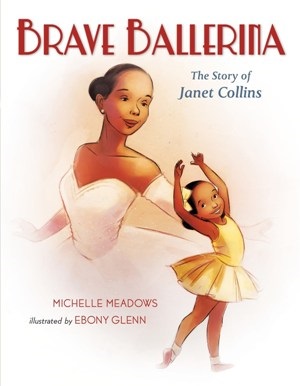

Many who read picture books in rhyme don't realize that writing poetry for kids is no easy feat--it's simply that those who do it well make it look easy. A fantastic recent example of this mastery of rhyming verse in picture book format is Michelle Meadows and Ebony Glenn's picture book biography Brave Ballerina (Holt, $17.99), about Janet Collins, "the first African American prima ballerina with the Metropolitan Opera House." Meadows's (Super Bugs) text almost never stumbles, keeping metronomic time with Ebony Glenn's illustrations of soaring, spinning Janet: "this is the time,/ way back in the day,/ when dance schools turned/ black students away." Glenn's (Mommy's Khimar) digital art is visual poetry, the dancers sketched in long, sinuous lines, the earth-toned shades of their clothing blending out into the background as they move. When the verse in this enchanting biography does not make the full story clear (such as when "the dancer/ who found her way in... learned she would/ have to lighten her skin"), an author's note gives detail, rounding out Janet's incredible story. (Janet "could only join the Ballet Russe on the condition that she paint her skin white." She refused.)

Many who read picture books in rhyme don't realize that writing poetry for kids is no easy feat--it's simply that those who do it well make it look easy. A fantastic recent example of this mastery of rhyming verse in picture book format is Michelle Meadows and Ebony Glenn's picture book biography Brave Ballerina (Holt, $17.99), about Janet Collins, "the first African American prima ballerina with the Metropolitan Opera House." Meadows's (Super Bugs) text almost never stumbles, keeping metronomic time with Ebony Glenn's illustrations of soaring, spinning Janet: "this is the time,/ way back in the day,/ when dance schools turned/ black students away." Glenn's (Mommy's Khimar) digital art is visual poetry, the dancers sketched in long, sinuous lines, the earth-toned shades of their clothing blending out into the background as they move. When the verse in this enchanting biography does not make the full story clear (such as when "the dancer/ who found her way in... learned she would/ have to lighten her skin"), an author's note gives detail, rounding out Janet's incredible story. (Janet "could only join the Ballet Russe on the condition that she paint her skin white." She refused.)

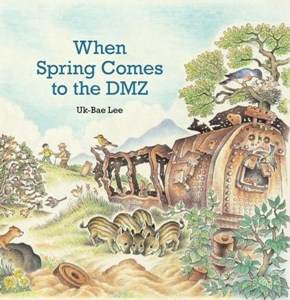

For a brilliant example of the poetry found in translated picture books, there is Uk-Bae Lee's When Spring Comes to the DMZ (Plough Publishing, $17.95). The internationally award-winning author/artist has never known a united country. He channels a hope for reunion into When Spring Comes to the DMZ, originally published in his native South Korea in 2010 as part of the Peace Picture Book Project, featuring illustrators from Korea, China and Japan. His text, smoothly translated by Chungyon Won and Aileen Won, is understated and simple, the English text mimicking in physical form the Korean from which it was translated. Further resonance is presented through his multi-layered illustrations, for example, the reader's first glimpse of the DMZ is the same as Grandfather's, the lush, green landscape seen through two circles entirely surrounded by black--mimicking the view from Grandfather's binoculars. With gentle words and glorious art, Lee inspires the newest generation of readers to lead the way and make miracles happen.

For a brilliant example of the poetry found in translated picture books, there is Uk-Bae Lee's When Spring Comes to the DMZ (Plough Publishing, $17.95). The internationally award-winning author/artist has never known a united country. He channels a hope for reunion into When Spring Comes to the DMZ, originally published in his native South Korea in 2010 as part of the Peace Picture Book Project, featuring illustrators from Korea, China and Japan. His text, smoothly translated by Chungyon Won and Aileen Won, is understated and simple, the English text mimicking in physical form the Korean from which it was translated. Further resonance is presented through his multi-layered illustrations, for example, the reader's first glimpse of the DMZ is the same as Grandfather's, the lush, green landscape seen through two circles entirely surrounded by black--mimicking the view from Grandfather's binoculars. With gentle words and glorious art, Lee inspires the newest generation of readers to lead the way and make miracles happen.

Poetry for an older group of children and teen readers has its own difficulties: reading level, accessibility, content.... Sometimes, it even has to fight poetry misconceptions young readers may have. Essayist, short-story writer and first-time children's novelist Aida Salazar's The Moon Within (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, $17.99) is a contemporary tale told in first-person verse about a girl reaching deep within herself for understanding. Salazar's language is frank and rich, using occasional Spanish or Mexica/Nahuatl words, as she describes 11-year-old Celi and her situation: a good student, dancer and drummer, she and her fellow Oakland, Calif., tweens are beginning to learn about their changing bodies and expressions of sexuality and gender. Celi struggles with her identity as a young woman, scared of the moon ceremony her mother wants to hold to celebrate her first period.

Poetry for an older group of children and teen readers has its own difficulties: reading level, accessibility, content.... Sometimes, it even has to fight poetry misconceptions young readers may have. Essayist, short-story writer and first-time children's novelist Aida Salazar's The Moon Within (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, $17.99) is a contemporary tale told in first-person verse about a girl reaching deep within herself for understanding. Salazar's language is frank and rich, using occasional Spanish or Mexica/Nahuatl words, as she describes 11-year-old Celi and her situation: a good student, dancer and drummer, she and her fellow Oakland, Calif., tweens are beginning to learn about their changing bodies and expressions of sexuality and gender. Celi struggles with her identity as a young woman, scared of the moon ceremony her mother wants to hold to celebrate her first period.

In Soaring Earth (Atheneum, $18.99), a companion to Margarita Engle's Pura Belpré Award-winning Enchanted Air (a poetic memoir about her early childhood), Engle recounts high school, her first failed experience in college and her eventual successful return. Soaring Earth is told in beautiful, brief poems, featuring Engle's experiences from Berkeley's tumultuous campus to a rat-filled apartment in New York. Throughout, Margarita's thirst for adventure is strong and bold, even when she sees herself as anything but daring or courageous. By holding other characters at arm's length, never naming with more than an initial, Engle keeps her narrative intimate, as though readers are viewing pages of her diary. Introspective and inquisitive, Soaring Earth traverses adolescence and early adulthood with grace, grit and unflinching realism.

In Soaring Earth (Atheneum, $18.99), a companion to Margarita Engle's Pura Belpré Award-winning Enchanted Air (a poetic memoir about her early childhood), Engle recounts high school, her first failed experience in college and her eventual successful return. Soaring Earth is told in beautiful, brief poems, featuring Engle's experiences from Berkeley's tumultuous campus to a rat-filled apartment in New York. Throughout, Margarita's thirst for adventure is strong and bold, even when she sees herself as anything but daring or courageous. By holding other characters at arm's length, never naming with more than an initial, Engle keeps her narrative intimate, as though readers are viewing pages of her diary. Introspective and inquisitive, Soaring Earth traverses adolescence and early adulthood with grace, grit and unflinching realism.

Also telling a story with "unflinching realism" is Laurie Halse Anderson's memoir-in-verse, Shout (Viking, $17.99). "Too many grown-ups tell kids to follow their/ dreams/ like that's going to get them somewhere/ Auntie Laurie says follow your nightmares instead/ cuz when you figure out what's eating you alive/ you can slay it." For two decades, Laurie Halse Anderson has been visiting schools and talking to teens about "rape mythology, sexual violence and consent." For two decades, "girls and boys" have sought her out to "tell [her], shame-smoked raw/ voices, tears waterfalling,/ about the time" they were assaulted. Anderson has spent 20 years as a repository for these stories of pain. And "those kids" who have shared, she writes, "taught me everything, those girls/ showed me a path through the woods/ those boys led me." Shout is a poetic biography, a call to action, a lesson, a fable, a warm embrace for those who hurt, a guttural scream demanding the pain stop. It's factual as it flows in lyrical verse through Anderson's life; speculative as she works to create a collective noun for teens ("a wince of teens/ mutter of teens/ an attitude, a grumble, a grunt"); direct as she speaks to scared librarians "on the cusp of courage." Shout is for survivors, for abusers and assaulters, for consenting young men and women, for gatekeepers unwilling to let sex through. Immensely powerful, this biography in verse is for everyone.

Also telling a story with "unflinching realism" is Laurie Halse Anderson's memoir-in-verse, Shout (Viking, $17.99). "Too many grown-ups tell kids to follow their/ dreams/ like that's going to get them somewhere/ Auntie Laurie says follow your nightmares instead/ cuz when you figure out what's eating you alive/ you can slay it." For two decades, Laurie Halse Anderson has been visiting schools and talking to teens about "rape mythology, sexual violence and consent." For two decades, "girls and boys" have sought her out to "tell [her], shame-smoked raw/ voices, tears waterfalling,/ about the time" they were assaulted. Anderson has spent 20 years as a repository for these stories of pain. And "those kids" who have shared, she writes, "taught me everything, those girls/ showed me a path through the woods/ those boys led me." Shout is a poetic biography, a call to action, a lesson, a fable, a warm embrace for those who hurt, a guttural scream demanding the pain stop. It's factual as it flows in lyrical verse through Anderson's life; speculative as she works to create a collective noun for teens ("a wince of teens/ mutter of teens/ an attitude, a grumble, a grunt"); direct as she speaks to scared librarians "on the cusp of courage." Shout is for survivors, for abusers and assaulters, for consenting young men and women, for gatekeepers unwilling to let sex through. Immensely powerful, this biography in verse is for everyone.

Poetry for Children and Teens

When Mary Oliver died in January, there was an outpouring of loss and remembrance. She was perhaps the most beloved poet of our age. Still, because she writes about old-fashioned subjects--nature, beauty and (gasp) God--she has not been taken seriously by many critics. Her deceptively simple poems and concomitant accessibility can mask her depth and profundity.

When Mary Oliver died in January, there was an outpouring of loss and remembrance. She was perhaps the most beloved poet of our age. Still, because she writes about old-fashioned subjects--nature, beauty and (gasp) God--she has not been taken seriously by many critics. Her deceptively simple poems and concomitant accessibility can mask her depth and profundity.

Benoîte Groult (1920-2016) was a French feminist writer and activist who was born into an upper-class Parisian family of fashion and furniture designers, attended the Sorbonne and worked as a television journalist. She co-wrote three books with her younger sister Flora before publishing her own novel in 1972. Groult went on to write 20 books and many essays. Much of her work concerns the history of feminism, gender discrimination and misogyny.

Benoîte Groult (1920-2016) was a French feminist writer and activist who was born into an upper-class Parisian family of fashion and furniture designers, attended the Sorbonne and worked as a television journalist. She co-wrote three books with her younger sister Flora before publishing her own novel in 1972. Groult went on to write 20 books and many essays. Much of her work concerns the history of feminism, gender discrimination and misogyny. Many who read picture books in rhyme don't realize that writing poetry for kids is no easy feat--it's simply that those who do it well make it look easy. A fantastic recent example of this mastery of rhyming verse in picture book format is Michelle Meadows and Ebony Glenn's picture book biography Brave Ballerina (Holt, $17.99), about Janet Collins, "the first African American prima ballerina with the Metropolitan Opera House." Meadows's (Super Bugs) text almost never stumbles, keeping metronomic time with Ebony Glenn's illustrations of soaring, spinning Janet: "this is the time,/ way back in the day,/ when dance schools turned/ black students away." Glenn's (

Many who read picture books in rhyme don't realize that writing poetry for kids is no easy feat--it's simply that those who do it well make it look easy. A fantastic recent example of this mastery of rhyming verse in picture book format is Michelle Meadows and Ebony Glenn's picture book biography Brave Ballerina (Holt, $17.99), about Janet Collins, "the first African American prima ballerina with the Metropolitan Opera House." Meadows's (Super Bugs) text almost never stumbles, keeping metronomic time with Ebony Glenn's illustrations of soaring, spinning Janet: "this is the time,/ way back in the day,/ when dance schools turned/ black students away." Glenn's ( For a brilliant example of the poetry found in translated picture books, there is Uk-Bae Lee's When Spring Comes to the DMZ (Plough Publishing, $17.95). The internationally award-winning author/artist has never known a united country. He channels a hope for reunion into When Spring Comes to the DMZ, originally published in his native South Korea in 2010 as part of the Peace Picture Book Project, featuring illustrators from Korea, China and Japan. His text, smoothly translated by Chungyon Won and Aileen Won, is understated and simple, the English text mimicking in physical form the Korean from which it was translated. Further resonance is presented through his multi-layered illustrations, for example, the reader's first glimpse of the DMZ is the same as Grandfather's, the lush, green landscape seen through two circles entirely surrounded by black--mimicking the view from Grandfather's binoculars. With gentle words and glorious art, Lee inspires the newest generation of readers to lead the way and make miracles happen.

For a brilliant example of the poetry found in translated picture books, there is Uk-Bae Lee's When Spring Comes to the DMZ (Plough Publishing, $17.95). The internationally award-winning author/artist has never known a united country. He channels a hope for reunion into When Spring Comes to the DMZ, originally published in his native South Korea in 2010 as part of the Peace Picture Book Project, featuring illustrators from Korea, China and Japan. His text, smoothly translated by Chungyon Won and Aileen Won, is understated and simple, the English text mimicking in physical form the Korean from which it was translated. Further resonance is presented through his multi-layered illustrations, for example, the reader's first glimpse of the DMZ is the same as Grandfather's, the lush, green landscape seen through two circles entirely surrounded by black--mimicking the view from Grandfather's binoculars. With gentle words and glorious art, Lee inspires the newest generation of readers to lead the way and make miracles happen. Poetry for an older group of children and teen readers has its own difficulties: reading level, accessibility, content.... Sometimes, it even has to fight poetry misconceptions young readers may have. Essayist, short-story writer and first-time children's novelist Aida Salazar's The Moon Within (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, $17.99) is a contemporary tale told in first-person verse about a girl reaching deep within herself for understanding. Salazar's language is frank and rich, using occasional Spanish or Mexica/Nahuatl words, as she describes 11-year-old Celi and her situation: a good student, dancer and drummer, she and her fellow Oakland, Calif., tweens are beginning to learn about their changing bodies and expressions of sexuality and gender. Celi struggles with her identity as a young woman, scared of the moon ceremony her mother wants to hold to celebrate her first period.

Poetry for an older group of children and teen readers has its own difficulties: reading level, accessibility, content.... Sometimes, it even has to fight poetry misconceptions young readers may have. Essayist, short-story writer and first-time children's novelist Aida Salazar's The Moon Within (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, $17.99) is a contemporary tale told in first-person verse about a girl reaching deep within herself for understanding. Salazar's language is frank and rich, using occasional Spanish or Mexica/Nahuatl words, as she describes 11-year-old Celi and her situation: a good student, dancer and drummer, she and her fellow Oakland, Calif., tweens are beginning to learn about their changing bodies and expressions of sexuality and gender. Celi struggles with her identity as a young woman, scared of the moon ceremony her mother wants to hold to celebrate her first period. In Soaring Earth (Atheneum, $18.99), a companion to Margarita Engle's Pura Belpré Award-winning Enchanted Air (a poetic memoir about her early childhood), Engle recounts high school, her first failed experience in college and her eventual successful return. Soaring Earth is told in beautiful, brief poems, featuring Engle's experiences from Berkeley's tumultuous campus to a rat-filled apartment in New York. Throughout, Margarita's thirst for adventure is strong and bold, even when she sees herself as anything but daring or courageous. By holding other characters at arm's length, never naming with more than an initial, Engle keeps her narrative intimate, as though readers are viewing pages of her diary. Introspective and inquisitive, Soaring Earth traverses adolescence and early adulthood with grace, grit and unflinching realism.

In Soaring Earth (Atheneum, $18.99), a companion to Margarita Engle's Pura Belpré Award-winning Enchanted Air (a poetic memoir about her early childhood), Engle recounts high school, her first failed experience in college and her eventual successful return. Soaring Earth is told in beautiful, brief poems, featuring Engle's experiences from Berkeley's tumultuous campus to a rat-filled apartment in New York. Throughout, Margarita's thirst for adventure is strong and bold, even when she sees herself as anything but daring or courageous. By holding other characters at arm's length, never naming with more than an initial, Engle keeps her narrative intimate, as though readers are viewing pages of her diary. Introspective and inquisitive, Soaring Earth traverses adolescence and early adulthood with grace, grit and unflinching realism. Also telling a story with "unflinching realism" is

Also telling a story with "unflinching realism" is