|

| (photo: Joe Kennedy) |

Jeanine Cummins was born in Spain, but calls Gaithersburg, Md., her home. She studied creative writing at Towson University before living in Belfast for several years. In 1997, Cummins moved to New York City, where she spent 10 years working in the publishing industry. After her first book, the memoir A Rip in Heaven, became a bestseller, she turned to writing full time. She is the author of the novels The Outside Boy and The Crooked Branch. Her novel American Dirt was just published by Flatiron Books.

Did you always want to be a writer?

I always dreamed of being a writer, but I didn't grow up with any sense that it was possible to make a living that way. My mom was a nurse and my dad was in the Navy. My grandfather was a professional musician, but even that seemed gritty, like a real job. He carried a tuba and bass around, which felt like tools to me. So I always thought I'd end up doing something practical. I thought I'd be a park ranger or a carpenter who submitted poems to local newspaper contests. But then my cousin Julie was murdered when I was 16. She was supposed to be the writer. So I think losing her, losing her talent, and understanding that the life she was supposed to live was no longer available to her, made me super determined to live out the dream we both shared, as if I had to do it now, for both of us. I like the idea that some of her flame may have landed on me when she departed.

In several interviews for your novel The Crooked Branch, you mention starting your book on immigration, but very differently. How did it evolve to its present state?

I'd like to say that it was meticulously planned and that its evolution was organic and beautiful, but the truth is that I wrote two failed drafts of this novel before it became what it needed to be. I was resistant, initially, to writing from the point of view of a Mexican migrant because, no matter how much research I did, regardless of the fact that I'm Latinx, I didn't feel qualified to write in that voice. Because these are not my life experiences. So I spent several years trying to write the book from a variety of perspectives, and all those perspectives failed. They were terrible. Because, ultimately, they were an inappropriate lens for the telling of this story.

But Luca emerged from that early cast of characters. My friend Mary Beth Keane kept pointing to him and saying, "He's the only one I care about." God bless her. I finally listened. I was terrified of going back to his origin story, of trying to truly inhabit the experiences of his life. But I did it as carefully as I could. And I'm glad I did. Because ultimately I remembered the thing that matters most in fiction: they are people. I do know Luca and Lydia; I know their lives. Because I know grief. I know trauma. So that's the thing. Yes, Luca and his mami happen to be Mexican, but they could be anyone. They could be Syrian or Rohingya or Haitian. They are human beings.

There are many emotionally powerful scenes in American Dirt. How did you go about creating these experiences in the book?

My research started with reading everything Luis Alberto Urrea ever wrote. Then I read everything else I could find about contemporary Mexico and by contemporary Mexican writers. Then I read everything I could find about migration. Sonia Nazario's Enrique's Journey is magnificent. So is The Beast by the Salvadoran writer Óscar Martínez. Then I went to Mexico. I spent time in the borderlands, both north and south of la frontera. I met people who are documenting human rights abuses at the border, people who drive out and leave water in the desert, lawyers who provide pro bono legal representation to unaccompanied minors. I visited two orphanages and several migrant shelters in Mexico. I volunteered at a desayunador in Tijuana, where they serve a hot meal to something like 300 migrants for free every day. I talked to people who were deep in their journeys, full of hope and fear. I met people recently deported, some of whom were veterans.

I met deported mothers who visited their U.S. citizen children at the border fence where only the tips of their fingers could touch through the thick metal screens. I even attended a wedding at Friendship Park where the deported bride married her U.S. Marine husband on the Mexico side of the fence, so her mother and U.S. citizen children could attend on the California side of the fence. I met a Guatemalan man whose leg was cut off when he fell from the train three days before he arrived at the Casa de Migrante in Tijuana. Every single person I met made me more and more determined to write this book. So, yes, many of the scenes were inspired by true stories I encountered in my research.

You started writing American Dirt before the current administration took office. Did their practices affect your writing and if so, how?

I started the research for this book in 2013, so way before anyone dreamed that the impetuous star of Celebrity Apprentice would become president of the United States. This problem pre-dated the current administration and, unfortunately, it will still be here after their time is up. But to be sure, the callousness is new. So there have probably been other presidents who felt some private disdain for the suffering of people who don't look like them, but the public expression of that scorn in the 21st century is still incredibly shocking to me. It's not only that the practices of the current administration are cruel, it's that they are gleefully so. It's unthinkable that the leader of our nation, which is supposed to be a symbol of hope and refuge in the world, is responding to the deaths of children in U.S. custody by tweeting things like "If Illegal Immigrants are unhappy with the conditions in the quickly built or refitted detentions centers, just tell them not to come." [sic] He doesn't recognize that the United States has a moral obligation to meet a humanitarian crisis with compassion. So, yes, that brutality has certainly intensified my feelings of panic about the crisis. Watching the president shrug and smile while so many people are dying needlessly on his watch makes me feel antagonized. I have a greater and greater sense of urgency about telling this story with each passing day.

If you could ensure that every reader would take away one thing from American Dirt, what would it be?

Migrants are human beings. They don’t need our pity or contempt. They deserve fundamental human empathy. They are LIKE US. --Jen Forbus

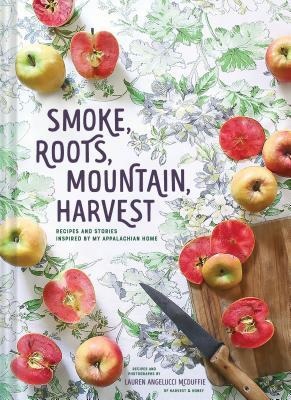

In Smoke, Roots, Mountain, Harvest: Recipes and Stories Inspired by My Appalachian Home (Chronicle, $29.95), Lauren McDuffie--the blogger behind Harvest & Honey--writes: "My favorite cookbooks, smudged and smeared with much use, rarely leave my kitchen counter." Clear some space and get ready to smudge and smear, for any of the following will surely suggest new go-tos for menus in the new year.

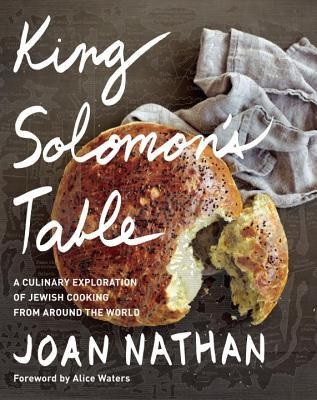

In Smoke, Roots, Mountain, Harvest: Recipes and Stories Inspired by My Appalachian Home (Chronicle, $29.95), Lauren McDuffie--the blogger behind Harvest & Honey--writes: "My favorite cookbooks, smudged and smeared with much use, rarely leave my kitchen counter." Clear some space and get ready to smudge and smear, for any of the following will surely suggest new go-tos for menus in the new year. In the stunning King Solomon's Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking from Around the World (Knopf, $35), veteran cookbook author Joan Nathan's recipes span continents and centuries, with fascinating historical and cultural context woven throughout. Dazzle friends with the spectacular T'Beet, Baghdadi Sabbath Overnight Spiced Chicken with Rice and Coconut Chutney. For dessert: Arkansas Schnecken, sticky buns redolent of caramel and pecans.

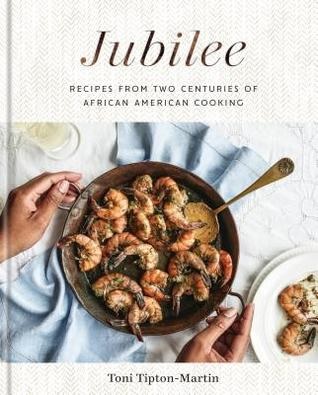

In the stunning King Solomon's Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking from Around the World (Knopf, $35), veteran cookbook author Joan Nathan's recipes span continents and centuries, with fascinating historical and cultural context woven throughout. Dazzle friends with the spectacular T'Beet, Baghdadi Sabbath Overnight Spiced Chicken with Rice and Coconut Chutney. For dessert: Arkansas Schnecken, sticky buns redolent of caramel and pecans. Culinary journalist and community activist Toni Tipton-Martin offers a similarly compelling and beautiful blend of education and instruction in Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking (Clarkson Potter, $35). Delight diners with Sweet Potato Biscuits and Curried Meat Pies, then serve up citrus-kissed Pork Chops in Caper-Lemon Sauce followed by Gingerbread with Lemon Sauce.

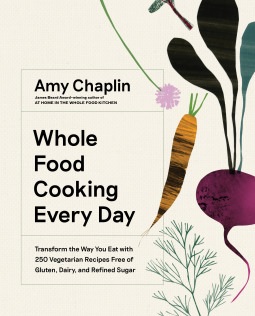

Culinary journalist and community activist Toni Tipton-Martin offers a similarly compelling and beautiful blend of education and instruction in Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking (Clarkson Potter, $35). Delight diners with Sweet Potato Biscuits and Curried Meat Pies, then serve up citrus-kissed Pork Chops in Caper-Lemon Sauce followed by Gingerbread with Lemon Sauce. For the health-conscious equally conscious of taste, see Amy Chaplin's Whole Food Cooking Every Day: Transform the Way You Eat with 250 Vegetarian Recipes Free of Gluten, Dairy, and Refined Sugar (Artisan, $40). Chaplin offers eye-popping, endlessly riffable dishes, like chia bowls, soups and veggie preparations--especially welcome amidst a winter of biscuits, sticky buns or gingerbread--all delicious, to boot.

For the health-conscious equally conscious of taste, see Amy Chaplin's Whole Food Cooking Every Day: Transform the Way You Eat with 250 Vegetarian Recipes Free of Gluten, Dairy, and Refined Sugar (Artisan, $40). Chaplin offers eye-popping, endlessly riffable dishes, like chia bowls, soups and veggie preparations--especially welcome amidst a winter of biscuits, sticky buns or gingerbread--all delicious, to boot.

Scottish author Marion Chesney Gibbons, who wrote more than 160 mystery and romance novels under several pseudonyms, died December 30 at age 83. She was best known for her Agatha Raisin and Hamish Macbeth mystery series, written as M.C. Beaton, and historical romance novels under the name Marion Chesney. She also wrote as Ann Fairfax, Jennie Tremaine, Helen Crampton, Charlotte Ward and Sarah Chester. Her Agatha Raisin and Hamish Macbeth titles have sold more than 21 million copies worldwide and have both been adapted into BBC television series.

Scottish author Marion Chesney Gibbons, who wrote more than 160 mystery and romance novels under several pseudonyms, died December 30 at age 83. She was best known for her Agatha Raisin and Hamish Macbeth mystery series, written as M.C. Beaton, and historical romance novels under the name Marion Chesney. She also wrote as Ann Fairfax, Jennie Tremaine, Helen Crampton, Charlotte Ward and Sarah Chester. Her Agatha Raisin and Hamish Macbeth titles have sold more than 21 million copies worldwide and have both been adapted into BBC television series.