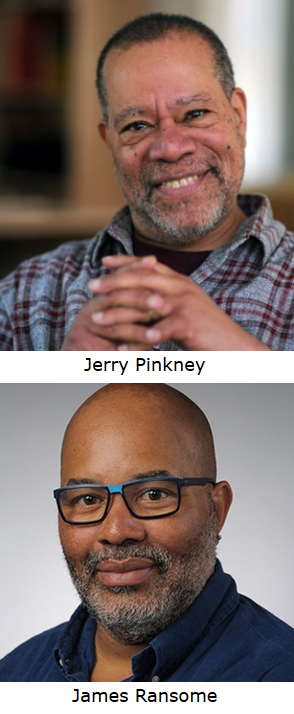

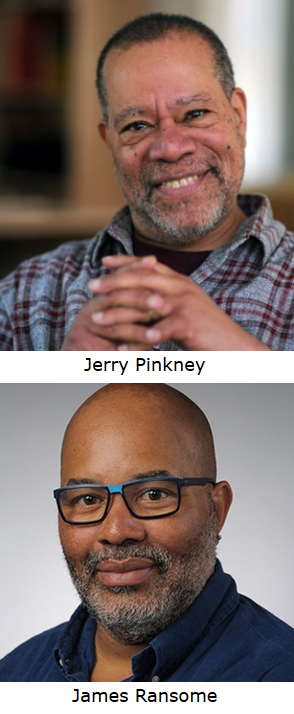

Author and illustrator Jerry Pinkney's accolades include the Caldecott Medal, five Coretta Scott King Awards, five Coretta Scott King Honor Awards, four New York Times Best Illustrated Books picks and four gold medals from the Society of Illustrators. He served on the National Council of the Arts, is a trustee emeritus of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art and has taught at New York's Pratt Institute, the University of Delaware and the University of Buffalo. He lives in Westchester County, N.Y.

Author and illustrator Jerry Pinkney's accolades include the Caldecott Medal, five Coretta Scott King Awards, five Coretta Scott King Honor Awards, four New York Times Best Illustrated Books picks and four gold medals from the Society of Illustrators. He served on the National Council of the Arts, is a trustee emeritus of the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art and has taught at New York's Pratt Institute, the University of Delaware and the University of Buffalo. He lives in Westchester County, N.Y.

James Ransome's numerous commendations include a Coretta Scott King Medal, two Coretta Scott King Honors and an NAACP Image Award. He lives in upstate New York with his wife and collaborator, writer Lesa Cline-Ransome. Here, the two discuss their long relationship, illustration and guidance for other artists.

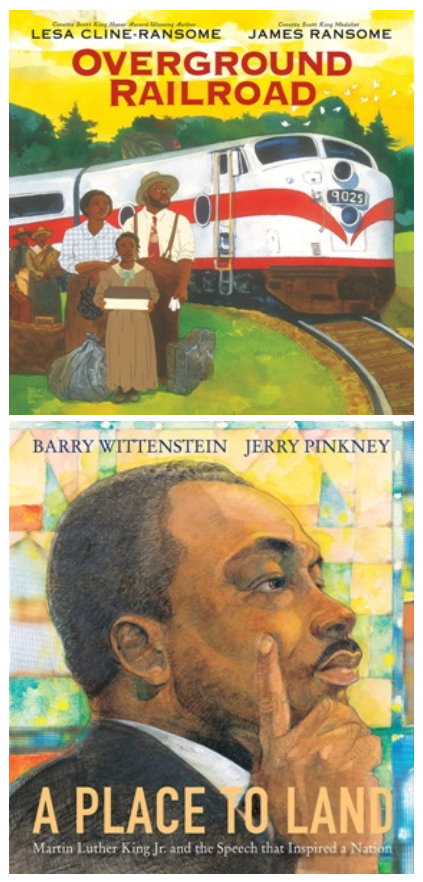

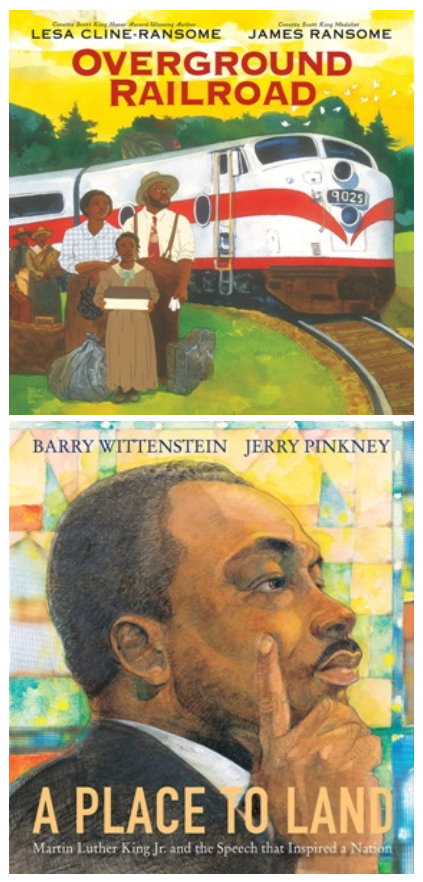

Please tell us about your most recent books, A Place to Land and Overground Railroad (both published by Holiday House).

Jerry Pinkney: A Place to Land, written by Barry Wittenstein, is a behind-the-scenes window into Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s process of drafting his iconic "I Have a Dream" speech. Dr. King delivered his remarks that hot day in August of 1968 on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and everything hinged on the moment Mahalia Jackson interrupted him with an encouraging shout of, "Tell them about the dream, Martin!" MLK switched course midstream, and the outcome of that speech was very much on par with Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, in that it propelled the idea of equality into our collective 20th-century American mystique.

There have been many moments in our nation's history that have altered the African American experience, among them slavery, the Underground Railroad, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Great Migration and the civil rights movement. James and I address two of these momentous events in our latest books.

James Ransome: Several years ago, I began reading Isabel Wilkerson's The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration. In Wilkerson's meticulous research, she recounts the stories of countless African Americans who traveled North from various points South, and those stories paralleled the travels of my own family, who left behind sharecropping and poverty in Rich Square, N.C., in the hopes of finding something better in Paterson and Newark, N.J.; Baltimore, Md.; and Brooklyn, N.Y. Overground Railroad, written by my wife, Lesa Cline-Ransome, is the story of Ruth Ellen and her parents traveling North aboard the Overground Railroad with the same hopes and dreams as so many other African Americans had who traveled during the Great Migration before and after the journey of Ruth Ellen and her family, all dreaming of a better future.

How did you two first meet? What were your first impressions of each other?

How did you two first meet? What were your first impressions of each other?

Pinkney: James and I first met at my studio in Croton-on-Hudson, N.Y. He had sent me a letter asking if I would entertain the idea of a meeting to review and critique his portfolio. I don't remember the specifics of the letter, but I can recall the articulate, passionate way he spoke about furthering his artistic practice. Over the years, I've received quite a lot of correspondence from aspiring young illustrators asking to spend time with me, but none was as earnest as James. I was eager to know more about this determined young Pratt graduate, so I took it upon myself to call him. We connected immediately. I recognized James as a person with infectious energy, and if he desired my help, I was happy to support his image-making efforts and dreams.

Ransome: During my sophomore year at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, I met a fellow illustration student named Scott Pinkney, and he told me his father was an illustrator named Jerry Pinkney. The following year, when I was a junior, Jerry began teaching an illustration class for seniors at Pratt, and even though I was only a junior, I introduced myself and often sat in on his classes. When I saw Jerry at the graduation ceremony the year Scott and I graduated, I saw him not only as an artist but as a husband and father, and that was inspirational. He was everything I was often told artists could not be. He was stable and creative, successful and an artist. He was normal. And that told me that I, too, could be a successful illustrator.

After graduation, when I received my first illustration job, I wrote to Jerry, asking if I could visit him in his studio, and he graciously agreed to see me.

You have a longtime personal and professional connection.

Pinkney: We've always had much in common and plenty to talk about. There is a landscape of mutual respect for what we both do: make narrative images. We also share a love of family as part of our DNA. I pursue that focus in my personal and art life, and I feel it whenever I am in the presence of James and his wife, Lesa, for any length of time. That generosity of spirit spills over to our larger family of artists, students and community.

Ransome: Jerry and I genuinely like each other. My wife teases me because she feels we are even beginning to dress alike. We have a shared love of jazz and very similar taste in artists. Since our very first meeting in his studio, Jerry has offered me the equivalent of a second degree in illustration, but, more importantly, he has been a guiding force, inspiration and dear friend for nearly 30 years. For me, Jerry is family.

James, what drew you to Jerry as an inspiration?

Ransome: I was first introduced to Jerry's work in the Society of Illustrator's Annuals. Browsing these catalogs and seeing the subject matter he painted, I often wondered if Jerry Pinkney was African American. It was only when I met his son, Scott, that I realized Jerry was his father. Scott and I often discussed his father's work and discussed going to visit Jerry's studio, but we were unable to make it happen with our conflicting schedules. When Jerry later began teaching at Pratt and then spoke to illustration students is when I first had the opportunity to meet him. In college, when Lesa brought me a copy of one of Jerry's books, The Patchwork Quilt, I was working on my portfolio. Before seeing his book, I thought only of being a sports illustrator, hopefully on assignment for Sports Illustrated magazine. After seeing Jerry's book, I added a series of images of a young girl to my portfolio, which caught the eye of an editor, the late Richard Jackson. It was because of that series that Richard offered me my very first picture book. So from the very beginning, Jerry has been a very big influence on my artwork, and I strive to meet the standards he has set.

Jerry, what made you want to take James on as a mentee?

Pinkney: It was his ability to see and demonstrate how, through dedication and hard work, artistic achievement is a promise. And that my investment would be rewarded in his own creative success.

Do you have words of advice for aspiring children's book illustrators?

Pinkney:

- Work at developing a sense of curiosity.

- Try looking at the world through as many lenses as possible.

- Look for and cultivate interests.

- Keep a sketchbook handy and draw daily. You can draw anything, and for whatever amount of time works for you--five minutes, 15 minutes or even longer. Feel free to return to the sketch later... or not. The goal is to foster mind, eye and hand coordination, and to explore mark-making and see where it leads.

- Push to surprise yourself. Remember: there is no failure in exploration.

Ransome: I agree wholeheartedly with everything Jerry listed, and I would add that it is important to also visit museums and galleries as often as you can to help you find the inspiration to surprise yourself. Always remember to experiment with color, layout, perspective and medium. And most importantly, visit bookstores and libraries to read and study children's books to see how current illustrators tell stories visually.

Jerry Pinkney and James Ransome: A Landscape of Mutual Respect

Newbery Award winner Mildred D. Taylor concludes the Logan family saga in the decades-spanning epic of self-discovery All the Days Past, All the Days to Come (Viking, $19.99, ages 12-up). Now a young adult, Cassie follows her brother during the Great Migration, eager to make a life away from the racism and brutality of their native Mississippi. But she quickly learns that while the North may not have "Whites Only" signs, segregation and racism persist throughout the post-World War II U.S.

Newbery Award winner Mildred D. Taylor concludes the Logan family saga in the decades-spanning epic of self-discovery All the Days Past, All the Days to Come (Viking, $19.99, ages 12-up). Now a young adult, Cassie follows her brother during the Great Migration, eager to make a life away from the racism and brutality of their native Mississippi. But she quickly learns that while the North may not have "Whites Only" signs, segregation and racism persist throughout the post-World War II U.S. Inspired by the strong women in their lives, The Old Truck, by debut author-illustrators and brothers Jarrett Pumphrey and Jerome Pumphrey ($17.95, Norton, ages 3-5), is a quietly powerful ode to hard work and perseverance. A farming family cheerfully toils through the seasons, using their red truck until it settles into the weeds by the weathered barn. The daughter works side by side with her parents, tinkering with the tractor and truck engines. Time passes. Now a grown woman, the next-generation farmer hauls the old truck out and works day and night to repair it.

Inspired by the strong women in their lives, The Old Truck, by debut author-illustrators and brothers Jarrett Pumphrey and Jerome Pumphrey ($17.95, Norton, ages 3-5), is a quietly powerful ode to hard work and perseverance. A farming family cheerfully toils through the seasons, using their red truck until it settles into the weeds by the weathered barn. The daughter works side by side with her parents, tinkering with the tractor and truck engines. Time passes. Now a grown woman, the next-generation farmer hauls the old truck out and works day and night to repair it. With Black Is a Rainbow Color (Roaring Brook Press, $17.99, ages 4-8), debut author Angela Joy pens a loving tribute to all the ways Black is beautiful. Caldecott Honor and Coretta Scott King Award-winner Ekua Holmes's brilliant collage illustrations elevate the text's themes of resilience and strength. With its charming simplicity, Black Is a Rainbow Color is a great way to begin unpacking a wide spectrum of connections and ideas behind the layered definitions of Black.

With Black Is a Rainbow Color (Roaring Brook Press, $17.99, ages 4-8), debut author Angela Joy pens a loving tribute to all the ways Black is beautiful. Caldecott Honor and Coretta Scott King Award-winner Ekua Holmes's brilliant collage illustrations elevate the text's themes of resilience and strength. With its charming simplicity, Black Is a Rainbow Color is a great way to begin unpacking a wide spectrum of connections and ideas behind the layered definitions of Black.

Author and illustrator

Author and illustrator  How did you two first meet? What were your first impressions of each other?

How did you two first meet? What were your first impressions of each other? In 1953, Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man won the National Book Award for Fiction, beating Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea and John Steinbeck's East of Eden. Ellison (1913-1994) did not publish another novel for the rest of his life. Instead, between essays and short stories, he produced an unfinished manuscript more than 2,000 pages long. His friend, biographer and literary executor John F. Callahan condensed Ellison's writing into Juneteenth, a 368-page novel published in 1999. With help from Adam Bradley, professor of English at the University of Colorado at Boulder, Callahan incorporated larger sections of Ellison's unfinished work into Three Days Before the Shooting..., a 1,101-page book published by Modern Library in 2010. It follows a man of unidentified race named Bliss, raised by a black Baptist minister, who adopts a white identity as an adult and becomes a racist U.S. Senator.

In 1953, Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man won the National Book Award for Fiction, beating Ernest Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea and John Steinbeck's East of Eden. Ellison (1913-1994) did not publish another novel for the rest of his life. Instead, between essays and short stories, he produced an unfinished manuscript more than 2,000 pages long. His friend, biographer and literary executor John F. Callahan condensed Ellison's writing into Juneteenth, a 368-page novel published in 1999. With help from Adam Bradley, professor of English at the University of Colorado at Boulder, Callahan incorporated larger sections of Ellison's unfinished work into Three Days Before the Shooting..., a 1,101-page book published by Modern Library in 2010. It follows a man of unidentified race named Bliss, raised by a black Baptist minister, who adopts a white identity as an adult and becomes a racist U.S. Senator.