|

| (photo: Topher Simon) |

Traci Cheeis the author of The Reader Trilogy and the novel We Are Not Free, coming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on September 1. She studied literature and creative writing at UC Santa Cruz and earned a Master of Arts degree from San Francisco State University. Chee spoke to Shelf Awareness about changing literary gears, sharing family stories and the intricacies of avoiding over-explaining.

Transitioning from worldbuilding fantasy to personally inspired historical fiction seems like quite the leap. Was it?

I've written speculative fiction for as long as I've been writing. For years, every story I wrote, even the ones I tried to make realistic, had a touch of the fantastical to it. Because my family was part of the Japanese American incarcerations of World War II, I've wanted to write a story about it for years and, at one point, I even thought I might inject a little fantasy into it--because what kind of a writer was I if I wasn't writing magic?--but all of that changed the deeper I delved into my research. The more books I read, the more museums I visited, the more relatives I interviewed, the more I realized that the magic was already there in the details and in the lived experiences of the incarcerees. I stumbled upon so many facts and anecdotes that I could never have made up, and that's what I've found so enchanting about writing historical fiction. That these things really happened, to real people.

When and how did you choose to explore their history through fiction?

I first learned about the incarceration when I was 12. My grandfather, who was 16 when he and his family were evicted from their apartment in San Francisco, was being awarded an honorary diploma from the San Francisco Unified School District, from which he would have graduated if not for the war and the incarceration. Although he was, I think, pretty honored to get it, he was also quoted in the newspaper as saying, "Where were the bleeding hearts in 1942?" I wasn't familiar with the term "bleeding hearts," but I could recognize that hard edge of bitterness and anger to his words.

When I started pursuing publication seriously, I always had in the back of my mind that I wanted to write about what had happened to my family. The problem was that I didn't know how. How could I hope to capture not only the anger and the bitterness but also the joy, the sorrow, the resentment, the sense of betrayal that so many of these Japanese American kids felt when the only country they'd ever called home stripped them of their civil rights and locked them up behind barbed wire? It just didn't seem possible to do that with a single story.

How did you decide the ideal narrative structure was 14 points of view?

[Rather than a] single story from a single point-of-view, I could tell these stories from the perspective of a group of people, like my grandparents and their friends, who grew up together in Japantown and were forced through this experience of war and incarceration, which changed them, scattered them across the country and also brought them closer together. It had to be a novel-in-stories: one chapter for each character, united by their love for one another.

How much of your family's actual history is contained in these pages?

I like to say that We Are Not Free is "loosely inspired" by my family's experiences, and that's because their stories have been transformed by fiction. I don't think you can point to a character and say that it's my grandmother or my grandfather, but I've given some of them my family stories. There's a character, Bette, who wears a blonde wig throughout the first few chapters of the book, and that wig comes from a story about my grandmother, who was enrolled in beauty school after the war. She came home one day wearing this blonde wig, and her father (my great-grandpa) was so upset, thinking she'd dyed her hair, that he started screaming at her. She just stood there, grinning, while he got madder, until finally she ripped off the wig, wagging it in his face and laughing. It's little moments like that where I've woven in family anecdotes, hopefully honoring those stories and the relatives who lived them.

What made you decide to write this book now?

I started interviewing relatives back in 2016, before the presidential election, but in the months that followed, news came out about the Muslim ban, immigrant detention centers and children being separated from their parents at the border. More and more, this history of injustice and persecution was alive and well in the 21st century. We need to remember we have committed heinous acts in the name of national security before, and they are not ones we should repeat. I think inspiration is often like that--a surprising confluence of events all coming together in urgency and spilling over into creativity.

You didn't translate most of the Japanese words. You also never used the catchphrase shikata ga nai ("it can't be helped"), prevalent in most Japanese American imprisonment narratives. What was your thinking behind that?

I love this question! Having never written historical (or contemporary, for that matter) before, negotiating these lines of "how much to explain" and "how much is over-explaining" was totally new for me. It came down to audience: Who is this book for? It's for my family. It's for my Japanese American community. It's for the larger Asian American community of which we are a part, because what happened to us in the 1940s and how we dealt with it influenced so much of what came after for other Asian American communities. And it's for American readers at large, many of whom have only heard of the mass incarceration as a passing reference in one of their high school textbooks, if at all.

In the broadest sense, I hope that context will carry the meaning for readers who don't speak Japanese or who are unfamiliar with certain customs or foods. You don't need to know exactly what takuan is, for example, to know that when the characters are pickling foods during rationing and food shortages, they're gearing up for further shortages to come. But if you know what takuan is, if you've eaten it over rice or opened up your fridge to that particular sweet-vinegar smell, then I hope it provides an added layer of specialness and meaning to the story.

As for shikata ga nai, omitting it was a deliberate choice. I suspect that for a lot of people, when the mass incarceration is brought up, it conjures this stereotypical idea of "noble Japanese suffering," right? Shikata ga nai--it can't be helped. A lot of existing narratives lean into this idea, and that's important, because it's certainly one type of experience that people had. But since that story had been told before, and told often, I wanted to explore some of the other experiences that Japanese Americans, particularly nisei teenagers, had. I wanted to delve into their anger, their sadness, their acts of resistance, whether that be in activism or in joy. So I chose to tell other stories, hopefully that will supplement and engage with the ones we already have. --Terry Hong

I remember at age seven, lying on the floor of the living room in our small Cape Cod-style home in Dearborn, Mich. When the narrator spoke of using a colored pencil, I took out a pencil, too, and drew around the "masterpiece" on the opening page. I loved that, where adults saw a hat, I could see the elephant inside the boa constrictor. (I still have that original book with my pencil marks.)

I remember at age seven, lying on the floor of the living room in our small Cape Cod-style home in Dearborn, Mich. When the narrator spoke of using a colored pencil, I took out a pencil, too, and drew around the "masterpiece" on the opening page. I loved that, where adults saw a hat, I could see the elephant inside the boa constrictor. (I still have that original book with my pencil marks.) In the new Everyman's Library edition, Richard Howard's translation from the French reads like poetry in its spareness and clarity and offers fans the chance to experience the text anew. He preserves the beauty of a child's view in the Little Prince's descriptions of his experiences and describes the enormity of that first true attachment: "You'll understand why yours is the only rose in all the world."

In the new Everyman's Library edition, Richard Howard's translation from the French reads like poetry in its spareness and clarity and offers fans the chance to experience the text anew. He preserves the beauty of a child's view in the Little Prince's descriptions of his experiences and describes the enormity of that first true attachment: "You'll understand why yours is the only rose in all the world."

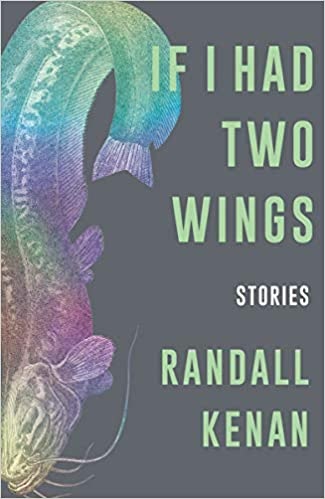

Randall Kenan, "the unapologetically Black, gay Southerner who used all his identities to tell the stories only he could tell," died August 28 at age 57, the

Randall Kenan, "the unapologetically Black, gay Southerner who used all his identities to tell the stories only he could tell," died August 28 at age 57, the