|

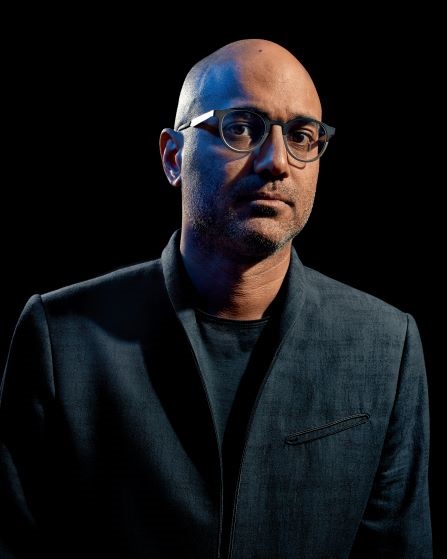

| photo: Vincent Tullo |

Born in New York and raised in Wisconsin, Ayad Akhtar is a novelist and playwright of Pakistani-Muslim ancestry. His first novel, American Dervish, and his plays, Disgraced and The Who and the What set the scene for what is, in his second novel, Homeland Elegies (reviewed below), an astonishing conversation about Muslim American self-identity. Disgraced won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2013, and two of Akhtar's four plays were nominated for the Tony Award for Best Play. He was recently named president of PEN America. We spoke with Akhtar via Zoom while he was socially distancing in upstate New York.

Where did the idea for Homeland Elegies originate, and for whom did you write it?

I was in Rome for two months, finding myself with a new perspective on my American homeland in the era of Trump. I was immersed in the works written during the classical tradition, and felt I was seeing things somehow more clearly, a picture of the nation focused by a larger historical frame. Something about the various divisions I'd been observing in American life over the past decade began to coalesce, not just intellectually, but emotionally. And I saw my own family's saga in America implicated in all of this, expressing it. One afternoon, in the library at the American Academy, I stumbled on a poem by Leopardi, the first in his Canti, entitled "To Italy." I read it and it ignited something in me--the idea of speaking to the nation. To my fellow citizens. To America. Less than 24 hours later, the opening of the book, substantially unchanged in its final form, poured out of me. I use the word "poured" for a reason. The entirety of this book quite literally poured out of me. Sentence by sentence, section by section--over the course of 11 months.

How did you decide to blend fact and fiction in crafting the story?

I was looking to write a literary form of serial reality entertainment, a literary corollary for the Instagram feed--a succession of inducements (both high and low) to keep the reader absorbed, scrolling on. A form that was in dialogue with the curated autobiographical self-staging that has become the dominant form of public discourse on social media, and which is now even our dominant political modality.

I am trying to meet the world where it is, in its thralldom to fiction-as-fact, in its confusion over the difference between a good story and the truth. I wanted to find a form that could embody this collapse, this confusion. Our lust for unreality--our trust in entertainment as a paradigm for consciousness itself. I wanted to find a language and form for a novel that could give it the teeth to speak to us directly about what matters, not metaphorically, not as a commentary upon, but as a voicing of the actual, of the essential, of the real.

A non-Muslim friend of yours, after reading the novel, commented that one almost had to be an outsider, maybe even Muslim, really to understand America. Is it advantageous to have an outsider's lens truly to comprehend this country?

I think being an outsider who is also an insider can be a unique perspective. It can make you see things that others don't naturally tend to notice. Being Muslim, for example, gives one a very particular perspective of both race and history in this country. There is a foreign policy history that much of the American public is not aware of, which makes it difficult for many to understand how something like 9/11 can happen. The less usual lens a Muslim-American has on the nation can be very illuminating and, in the case of that particular friend, that lens helped him to see the country and the current dilemmas we are living through more clearly.

In Homeland Elegies you explore the difference between the America your parents were drawn to in the 1960s and the country as it exists now. If they had to do it again, do you think they would leave Pakistan and come here today?

In Homeland Elegies you explore the difference between the America your parents were drawn to in the 1960s and the country as it exists now. If they had to do it again, do you think they would leave Pakistan and come here today?

Probably not. My father said as much toward the end of his life. Back when he was younger, American prosperity was still married to a sense of aspirational, even moral, supremacy. Today, the American aura for folks around the world has definitely changed.

You describe yourself as a cultural Muslim. May I ask what that means to you?

I have been raised on the ethos and mythos of Islam. It has shaped me. It has shaped my aesthetics and my sense of the power of the unseen. But I am not a believer in the unique importance and primacy of the Quran in human history. I haven't been a "believer"--practicing or otherwise--since my late adolescence, when, as with so many, my childhood faith foundered upon the shores of my intellectual development. But I do still find deep inspiration in the Islamic tradition, as I do in others. I am an avid and repeated reader of the Old and New Testaments, Meister Eckhart, the Vedas, Ibn Arabi.

The narrator experiences perceptive dreams that lend shape and context to a number of his actual experiences. Does that happen to you too?

This is a perfect example of the Muslim imprint. Indeed, I have an active dream life that I pay close attention to. Dreams are very important in many Muslim cultures, and I grew up with that. My approach to dreams is less inspired by Joseph (or Yusuf to Muslims) and more Jung these days, though!

In writing the book you say it consolidated something in you, a sense of belonging. Can you elaborate on that?

I think what happened to me in writing this book happens to many writers when they finally release long stored up things. I wasn't aware just how much kindling I had been gathering until the writing ignited in me, and there's no question that the ensuing conflagration consolidated something essential in me. I'm not sure it's belonging as such, though I do feel, somehow, clearer about the question of belonging. In the wake of writing Homeland Elegies, I feel more undivided than I ever have.

As a son of Pakistani American doctors, how did your parents react when you informed them of your decision to pursue a career in theater?

Just as in the book, they didn't really understand. Hard to blame them! A career in the theater? What's that? But they were ultimately supportive of me. Unusually so, considering what I've seen many of my artistic desi (South Asian) friends and colleagues go through. But again, it all makes sense. As immigrants, security feels that much more precarious--and the fear that one won't find a place can be that much more decisive and intense.

The chapter revealing the Islamic origins of various family members' names touches upon the system of arranged marriages and "love" marriages in Pakistani culture. Was there any pressure on you to submit to an arranged marriage?

Alas, no. My maternal grandmother brought it up once in my mid-20s, and after my response, no one else in the family ever brought it up again!

If you could move to any country in the world, where would you choose to live?

This one. As the end of the book makes clear, I love this country for better and worse. It is the only home I've ever known. I don't long for another. --Shahina Piyarali, writer and reviewer

Ayad Akhtar: 'Our Lust for Unreality'

I fell in love with Brit Bennett's writing in her 2016 debut, The Mothers (Riverhead, $16), a powerful story of race and motherhood and coming-of-age. The Vanishing Half (Riverhead, $27) lived up to every one of my expectations from Bennett, delivering a compelling and ruminative story of two twins, one who lives as a white woman and one as a black woman, and the many ways race runs cracks down their lives--and the lives of those around them.

I fell in love with Brit Bennett's writing in her 2016 debut, The Mothers (Riverhead, $16), a powerful story of race and motherhood and coming-of-age. The Vanishing Half (Riverhead, $27) lived up to every one of my expectations from Bennett, delivering a compelling and ruminative story of two twins, one who lives as a white woman and one as a black woman, and the many ways race runs cracks down their lives--and the lives of those around them. Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing (Vintage, $16.95), also a 2016 debut, dealt with many similar themes: race and racism, and the legacy of both on generations of one family. I tore through her second novel, Transcendent Kingdom (Knopf, $27.95), with equal fervor, desperate to understand the ways that faith and science intersect in the life of Gifty, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience, especially as they relate to the experience of losing her brother to addiction.

Yaa Gyasi's Homegoing (Vintage, $16.95), also a 2016 debut, dealt with many similar themes: race and racism, and the legacy of both on generations of one family. I tore through her second novel, Transcendent Kingdom (Knopf, $27.95), with equal fervor, desperate to understand the ways that faith and science intersect in the life of Gifty, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience, especially as they relate to the experience of losing her brother to addiction. Shelf's review called Nicole Dennis-Benn's debut, Here Comes the Sun (Liveright, $15.95), a "stunning, multi-layered novel" that explores "the implications of race, reputation, class and money." Those same qualifiers could easily be applied to her follow-up novel, Patsy (Liveright, $16.95), which proves her place as an author capable of using vivid backdrops and complex, nuanced characters to explore the gray area that arise when those four themes converge in one life.

Shelf's review called Nicole Dennis-Benn's debut, Here Comes the Sun (Liveright, $15.95), a "stunning, multi-layered novel" that explores "the implications of race, reputation, class and money." Those same qualifiers could easily be applied to her follow-up novel, Patsy (Liveright, $16.95), which proves her place as an author capable of using vivid backdrops and complex, nuanced characters to explore the gray area that arise when those four themes converge in one life.

In Homeland Elegies you explore the difference between the America your parents were drawn to in the 1960s and the country as it exists now. If they had to do it again, do you think they would leave Pakistan and come here today?

In Homeland Elegies you explore the difference between the America your parents were drawn to in the 1960s and the country as it exists now. If they had to do it again, do you think they would leave Pakistan and come here today? Winston Groom, "a Southern writer who found a measure of belated celebrity when his 1986 novel, Forrest Gump, was made into the 1994 Oscar-winning film starring Tom Hanks," died September 17 at age 77, the

Winston Groom, "a Southern writer who found a measure of belated celebrity when his 1986 novel, Forrest Gump, was made into the 1994 Oscar-winning film starring Tom Hanks," died September 17 at age 77, the