|

|

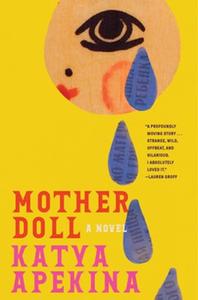

| Katya Apekina (photo: Lena Rudnick) |

|

Katya Apekina was born in Moscow and moved to the United States as a young child. Her debut novel, The Darker the Water the Uglier the Fish, was widely praised for its originality and willingness to tackle the dark edges of humanity. In addition to writing novels, she has worked as translator and a screenwriter in Los Angeles, where she lives with her husband and daughter. In Mother Doll (Overlook Press), she nests stories within stories--both of individual struggles like becoming a mother and of collective struggles like the Russian Revolution of 1917.

How did you land on Mother Doll as the title?

The title came at the very end. I had a different working title that I didn't like, and I was trying to come up with something. It was actually my agent who suggested Mother Doll, and I agreed that it was perfect. I like that it invokes the baby doll/mother doll element as well as the matryoshka or nesting doll without being so direct about it. It brings in the generational stuff, this idea that we're containing multiples inside of us, that is present in the book. Both in terms of our ancestral experiences but also the different aspects or eras of our own life, that we contain nestled inside of us. And then there's the physical experience of Zhenia being pregnant, so she's literally containing another generation inside of her.

There are unexpected elements in this story, communication with the dead through a medium being one. Was that level of supernatural always present in the work, or did it take that shape as you wrote?

The seed for the book came from my grandmother. She had given her memoirs to me before she died, but I started reading them after she died. So that sense of talking to the dead through a text was an entry point, but I wanted it to feel more alive than an interaction with a text. I wanted it to feel more embodied. Of course, we're constantly haunted by metaphorical ghosts of our ancestors, so I made it literal as a way of exploring that. Mother Doll is talked about sometimes as being a ghost story, which it literally is, but people have expectations from a ghost story that this book is probably going to subvert. The kind of haunting and scary stuff that happens in this book is more about abandonment and generational trauma. And it's also probably more funny than scary in some ways.

The book does such a good job of showing the act of listening to be a physical, fully engaging process. The medium Paul physically secluded himself in a closet to allow Irina's story to pass through his body into the phone, with Zhenia on the other end to receive it. There are layers of listening here. Do you feel listening is critical to the act of creation?

The book does such a good job of showing the act of listening to be a physical, fully engaging process. The medium Paul physically secluded himself in a closet to allow Irina's story to pass through his body into the phone, with Zhenia on the other end to receive it. There are layers of listening here. Do you feel listening is critical to the act of creation?

Absolutely. As I was writing this book, I was also with my grandfather in his last weeks, and he was dictating his memoir to me. It was this act of receiving, and I was affected physically by the intense listening, by the taking on of another person's story. That bearing witness is not a neutral thing. It does take a lot of energy--emotional and physical energy. So I was thinking about that as I was writing. There's a difference between the listening that might happen as an eavesdropper versus as a journalist who is actively engaging with and taking on the responsibility for someone's story.

I actually took some mediumship classes and psychic meditation classes as research, and it's a strange physical feeling of receiving a story that feels external from you, and you're almost just transcribing. That's what writing sometimes--at its best--feels like. When it works, it feels so good to feel that you have a connection with something outside yourself that you're just letting pass through you.

Becoming a mother changes a person, in obvious and less obvious ways. What would you say are some of those transformational changes?

When I had a daughter of my own, I started thinking concretely about myself as part of this generational chain. Maybe I would have thought about that anyway at a certain time in my life, but for me, having my daughter made me think about my mother's experience, my grandmother's experience. Being on the other side of daughterhood, it made me think a lot about them. Similarly for Zhenia, it helps her begin to process this ancestral trauma that has made her feel like her life has no agency. When this big--almost external--event of having a child happens to her, it forces her to think about things differently, and it leads to her making choices where she begins to be more connected with what it is she wants, with what her desires are.

In the book, desire is often born out of a deep lack of something--food or connection or stability. But there is a more positive form of desire, one born out of a sense of hope. As Zhenia figures out what she wants, does that negative desire transform into something more positive?

At the end, when Zhenia is with Chloe and Anton, the desire she experiences is more hopeful. It's a complicated relationship because it's not very honest, and she's afraid of losing what she has by being honest about it. But the desire there feels satiated. And her relationship with her baby is very joyful and satisfying to her. A lot of times when you read about parenthood, there's a lot of emphasis on how difficult it is, which it is, but it is also often very fun and joyful, and I wanted to show that.

Irina often struggles with her own sense of cowardice, times when she felt she acted bravely and others when she did not. How would you define bravery, especially as seen through some of those different perspectives?

The idea of bravery in the context of the Revolution is one thing. But what does it mean to be brave in the context of Zhenia's life? Maybe it means to live the life that she actually wants and understand what that is. In the beginning of the book she's just doing what's expected of her. When she begins to do things that from the outside might look like a bad idea, but to her, feel like the right thing, that is a form of bravery. Obviously being brave in her life looks very different, but confronting your ancestral baggage is difficult, and it does require courage. To be honest about things requires a certain amount of courage, and it's courage that Zhenia may not have yet, but it seems she will soon. --Sara Beth West