| Publisher: | Soft Skull Press | |

| Genre: | Humorous, Black Humor, Satire, Literary, Coming of Age, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781593763909 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $16.95 |

| Starred | Fiction |

by Lucy Ives

Loudermilk, the second novel from poet Lucy Ives (Impossible Views of the World), is a book where profound poststructuralist meditations on language, chance and creativity are deftly spun through with a myriad of jokes about farting, sex and male anatomy. The novel centers on handsome Troy Augustus Loudermilk, who wins a fellowship to a famed Midwestern creative writing institution by using his friend Harry's poetry. Harry Rego--directionless, agoraphobic and bearing close resemblance to "a hobbit or shaved teddy bear"--follows Loudermilk to the Midwest, agreeing to be his ghostwriter in exchange for a spare room. With the Bush presidency and invasion of Iraq playing out ambiently and calamitously in the background, Loudermilk perfectly captures the strange cultural ethos of the early 2000s.

Although Loudermilk's frat-boy antics and inexplicable charisma are the heart of the novel, Loudermilk is also populated with a number of other characters ranging from plotting to pathetic: one-time award-winners with perpetual writer's block, drunk professors, scorned geniuses and teenagers on their worst behavior. Throughout the course of the novel, Ives produces distinct writing as every one of these characters, prompting the reader to consider the ways in which creativity often involves accessing other selves and inhabiting different personas. With razor-sharp prose and a plenitude of linguistic strangeness, Ives has written a novel about American college life that is both philosophically gripping and exceptionally hilarious. --Emma Levy, bookseller at Third Place Books Seward Park, Wash.

| Publisher: | Sourcebooks | |

| Genre: | Women, Small Town & Rural, General, Fiction, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9781492671527 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $15.99 |

| Fiction |

by Kim Michele Richardson

A determined and forthright Cussy Mary Carter tells her story in The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek. In her fourth novel, Kim Michele Anderson gives her a voice true to the Appalachian backwoods of "western Kaintuck" in the 1930s.

At 19, Cussy hopes to overcome a lifetime of poverty and scorn, when she joins the Works Progress Administration's Pack Horse Librarians program "to put females to work and bring literature and art into the Kaintuck man's life." Cussy got the job against her ailing coalminer father's objections that "a workin' woman will never knot." Finding her a husband will be hard enough, Pa knows, because she's a "Blue"--the last of a blue-skinned clan descended from French Blues who'd settled there four generations back. But Cussy perseveres, and on her reliable mule Junia, she's welcomed as "the Book Woman" by her patrons, whose isolated cabins are spread out for miles. In spite of her own hardships, she shares what little she has, and relishes "bringing a hopeful world into their dreary lives and dark hollers."

A heroine richly deserving of happiness, Cussy does find love and joy, but in the author's historically accurate plot it's compromised in an episode of prejudice and violence. Pack Horse librarians, Troublesome Creek and the blue-skinned people of Kentucky were all real, and their story, as Cussy tells it, is a bittersweet homage to an unusual time and place. --Cheryl Krocker McKeon, manager, Book Passage, San Francisco

| Publisher: | Counterpoint | |

| Genre: | Family Life, Small Town & Rural, General, Literary, Coming of Age, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781640091771 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $26 |

| Fiction |

by Pete Fromm

When Marnie slips the pregnancy test from her tool belt, surprising Taz as they're demo-ing their fixer-upper, he's dumbstruck but pleased. A Job You Mostly Won't Know How to Do feels like a comedic novel of young parenthood. Then, just before the birth, they make a romantic last visit to their favorite secluded fishing spot in the Montana mountains near Missoula, Pacific Northwest author Pete Fromm's (The Names of the Stars) favorite setting. Their situation seems idyllic, but Fromm has another story to tell: of resilience in the face of incomprehensible tragedy.

Marnie delivers Midge, clutches Taz's hand and in an instant, he is a widower with a newborn daughter. Ensuing chapters are titled "Day One" through "Day Five Fifteen" as Taz grapples with grief and fatherhood. While Taz forms an awkward bond with Marnie's mother--a tender storyline--it's their friend Rudy who becomes an unlikely uncle to Midge. His beer-drinking, irregular schedule and droll wit serve as comic relief to the novel's sorrow. (When Taz balks at taking days-old Midge to the club, Rudy says, "She doesn't have to order anything!") He's there, always, sometimes on the porch before Taz even realizes he needs him. He helps Taz resume his carpentry work, and arranges an introduction to Elmo--the bartender-turned-nanny who stabilizes their lives, becoming Midge's "Momo." Taz dotes on Midge, and when the ever-present voice of Marnie eventually says, "The future, it's where you're headed, you can't help that," Taz allows himself to once again feel joy. --Cheryl Krocker McKeon, manager, Book Passage, San Francisco

| Publisher: | Dzanc Books | |

| Genre: | Psychological, Women, General, Fiction, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9781945814846 | |

| Pub Date: | March 2019 | |

| Price: | $16.95 |

| Fiction |

by Carolyn Kirby

Are we born bad, or do our circumstances shape us?

That's the question burning at the heart of Carolyn Kirby's debut novel, The Conviction of Cora Burns. The eponymous protagonist was born in the Birmingham Gaol (jail) to a mother she never knew. Twenty years later--after a harsh childhood in a workhouse, and several years as a laundress at an asylum--she returns to the gaol as a prisoner, having committed a yet-to-be-revealed crime. On the day of her release, she's sent onto the streets with nothing but her wits, her temper and a tarnished, broken medal bearing a cryptic engraving. Cora is certain that the medal's missing half will lead her to her long-lost friend, Alice Salt--a girl with whom she shared a profound bond, a twin-like resemblance and an unspeakable childhood transgression. Instead, the medal leads her into the dark machinations at the home of Thomas Jerwood, a "gentleman scientist" who is determined to prove that criminality is hereditary.

Kirby seems to be challenging readers to understand the social and economic contexts that often determine people's fates, and to view what Jerwood cruelly calls "the lower orders" with empathy and nuance. With its complex anti-heroine and its dark, twisting plot, The Conviction of Cora Burns is haunted by transgenerational trauma, twins and doubles and the painful legacies of maternal sacrifice. All at once, it's a historical thriller, a ghost story and a sneakily political treatise on the need for a more equitable society. --Hannah Calkins, writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

| Publisher: | Crown | |

| Genre: | Espionage, Mystery & Detective, International Crime & Mystery, Suspense, Thrillers, Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781524761509 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $27 |

| Mystery & Thriller |

by Chris Pavone

Paris, 9:17 a.m.: A Middle Eastern man walks into the Louvre courtyard, wearing a suicide vest and carrying a briefcase. Across the Seine, Kate Moore (expat housewife, frustrated American intelligence agent) hears the sirens and wonders what has happened, and whether it has anything to do with her. Meanwhile, Kate's husband, Dexter, is preparing for one of the biggest stock-trading days of his career, as his former colleague Hunter Forsyth, tech CEO, readies himself for a huge announcement. But none of these people, or their actions, are exactly what they seem. Chris Pavone returns to the setting and protagonist of his debut novel, The Expats, in his fourth propulsive thriller, The Paris Diversion.

Pavone (The Travelers, The Accident) plots his narrative as tightly as a labyrinth of Paris streets, its threads twisting, doubling back and occasionally intersecting in surprising ways. He combines international political posturing, round-the-clock television coverage of terrorist events (real or potential) and the machinations of global tech companies with the quieter domestic drama of two marriages long plagued by secrets and lies. Adding a compelling layer are the minor characters and settings: a Louvre sniper called Ibrahim, a quick trip to an unnamed but highly recognizable Left Bank bookstore, several women who are much more than their administrative job titles suggest. Readers may think they know how Pavone's smart, stylish story will turn out, but his gift for illusion (rendered in crystal-clear prose) means nothing is certain until the last page--if then. --Katie Noah Gibson, blogger at Cakes, Tea and Dreams

| Publisher: | Viking | |

| Genre: | Biography & Autobiography, Women, Music, Personal Memoirs | |

| ISBN: | 9780735225176 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $28 |

| Biography & Memoir |

by Ani DiFranco

Maybe it began the summer when young Ani DiFranco wanted to spend more time at a horse camp than her parents were willing to pay for. DiFranco raised the extra money herself through babysitting, selling her possessions and otherwise honoring the DIY creed with which her name is now synonymous. As the Grammy-winning singer-songwriter writes in her memoir, No Walls and the Recurring Dream, "My utter conviction that I don't need anyone or anything but myself to do what I need to do in life got me through childhood and... has also been the essence of my superpower."

DiFranco, who was born in 1970 and raised by bohemian parents in Buffalo, N.Y., began performing music with her guitar teacher when she was about 10. By high school, she knew her path: she created a three-year course plan and graduated at 16, becoming an emancipated minor. Her fame was gradual and hard-won, achieved through schlepping to every gig offered and creating Righteous Babe Records in 1990. "The point was not to conquer the world of business so much as to devise a way of having a career in music without having to associate with businesspeople at all."

Fans of DiFranco's music know that she can write lyrics, and No Walls and the Recurring Dream's prose employs a similar playful acuity (Pete Seeger would "reach around behind the heads of people he was talking to and turn off the spotlight they had trained on him"). The book tracks DiFranco's career only through 2001; let's hope for an encore. --Nell Beram, author and freelance writer

| Publisher: | Holt | |

| Genre: | Biography & Autobiography, Baseball, United States, Sports & Recreation, 20th Century, History, Sports | |

| ISBN: | 9781250182036 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $28 |

| Starred | Sports |

by Kevin Cook

When Kevin Cook launches into the sagas of the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies, fan partisanship gives way to the lore of two of the league's oldest teams. In Ten Innings at Wrigley, Cook delves into the culture of baseball at a tipping point through a May 17, 1979, rubber match that turned into "the wildest ballgame ever."

Cook admirably winnows remarkable team histories to set the table. The Cubs, "born to lose" and cursed by a goat, were not a big market team in 1979, with Wrigley (a character in its own right) used for other events (e.g., ski-jumping contests) to make money. The Phillies were also "lovable losers," the last original franchise yet to win a World Series. But they were on the rise with something to prove, winning three straight division titles.

The game supports an inning-by-inning and pitch-by-pitch written recounting. With winds gusting to 30 mph, six runs in the first 10 minutes, 97 total bases and a run total of 45 that stands as the second highest of all time, the garbage truck fire beyond the bleachers is a mere afterthought. Many of the game's legendary and most colorful characters were playing (Rose, Bowa, Buckner, Kingman, Maddox) on the brink of epic cultural and league changes--cable television, the high-five, facial hair, computers, labor strikes and modern metrics, to name a few. Cook seamlessly blends these issues into this reconstruction of the game and its aftermath, a slice of history fans of any team will relish. --Lauren O'Brien of Malcolm Avenue Review

| Publisher: | Pegasus Books | |

| Genre: | Nature, Pets, Psychology, Health & Fitness, Animal & Comparative Psychology, General, Healing, Animal Rights | |

| ISBN: | 9781643130705 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $27.95 |

| Pets |

by Aysha Akhtar

"Animals provide steady comfort in the midst of chaos," writes Dr. Aysha Akhtar in her moving--if occasionally enraging--second book, Our Symphony with Animals: On Health, Empathy, and Our Shared Destinies. "As with human bonds," she continues, "our love for animals can foster in us a sense of security and well-being." Akhtar, a physician and deputy director of the army's Traumatic Brain Injury Program, explores just how deep that love goes by speaking with a range of pet owners, including victims of domestic violence and homeless people. She concludes from these firsthand interviews as well as from expert studies that human relationships with animals can sometimes truly mean the difference between life and death. In one especially poignant chapter, she interviews a woman who was beaten by her partner. The dog would repeatedly jump between the man and the woman to protect her, ultimately receiving those blows instead.

Akhtar, who also writes frankly in the book about her own childhood abuse and the dog who saved her, explains that society's most vulnerable people would fare far better, both physically and psychologically, if we could offer more care for their pets. Fewer than 200 women's shelters in the United States, she writes, allow pets in their facilities. As a result, many women stay with their abusive partners. The homeless are also healthier and happier with their pets, but often lack access to medical care when their animals fall ill. Our Symphony with Animals is a timely and necessary book that sheds light on how far animals will go to help us, and how much better we need to treat them in return. --Amy Brady, freelance writer and editor

| Publisher: | Oxford University Press | |

| Genre: | Biography & Autobiography, Music, Individual Composer & Musician | |

| ISBN: | 9780190651763 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $21.95 |

| Performing Arts |

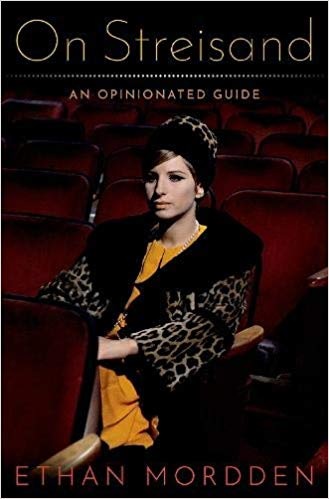

by Ethan Mordden

Prolific novelist and American music theater expert Ethan Mordden (All That Jazz) offers a fascinating, perceptive and very concise overview of Barbra Streisand's six-decade career in the studio, on stage, TV and screen. On Streisand: An Opinionated Guide examines and evaluates her prodigious output (she's won 10 Grammys, two Oscars and five Emmy awards) with a keen and critical eye. He also looks at her motivation behind each project. "Streisand is not a creature of impulse," writes Mordden. "She makes considered--even excruciatingly interrogated--judgment calls, because her work is her identity."

While Mordden is a fan, he's not undiscerning. Discussing her most recent two CDs, he notes, "We can no longer avoid noticing that Streisand's instrument is truly in decline." And while her 1976 movie A Star Is Born was a massive hit, Mordden notes that with her re-editing, she created "a love story with only one person in it." But he champions her amazingly assured directorial debut, Yentl, as well as Hello, Dolly!, Funny Girl and the problematic The Way We Were. Mordden folds in Streisand's personal life, her difficult reputation (sometimes earned, sometimes not) and how her genuine distinctiveness worked for and against her. "She was an Original, and many people dislike Originals--at first," he writes. Her movie career slowed down when she became "a compulsive ditherer... endlessly changing her mind about everything."

On Streisand is a thoughtful, perceptive and at times analytical look at Streisand's creative output and working methods. Mordden's engaging examination celebrates and deepens an appreciation of Streisand and her body of work. --Kevin Howell, independent reviewer and marketing consultant

| Publisher: | Graywolf Press | |

| Genre: | American, General, Poetry | |

| ISBN: | 9781555978419 | |

| Pub Date: | May 2019 | |

| Price: | $16 |

| Poetry |

by Tess Gallagher

Tess Gallagher (Dear Ghosts) elucidates liminal spaces in her fully realized poetry collection Is, Is Not.

The book is divided into eight sections, all bearing Gallagher's richly layered and evocative style. Her poems are wide-ranging in form and content, switching from long, complex, flowing meditations to terse, single-stanza observations. She considers the natural world as much as the human world, with a keen eye for where the two meet. Much of Is, Is Not straddles the boundaries between wilderness and civilization, between history and oblivion, life and death. In "Your Dog Playing with a Coyote," the poet writes of "Some ancient tincture of permission/ allows the edge of night/ to blend where wild and tame/ exchange fur in one naked, human/ mind."

Exploring these thresholds changes the poet's perception of the world and the nature of language itself. In "the night-nest of one mind" mingle impressions, memories and words, blending the objective world with the subjective self. Poetry, the poet maintains, springs from this melding of worlds.

Gallagher is as cerebral and intellectual as she is evocative and sensuous. These poems delight with their willingness to trespass into unknown realms of thought and being. The result is a heady reading experience. As she says in "Encounter," one of the collection's best, "A small entitlement of steps/ led me to mystery, seeking to be/ left out." She then asks: "How else let difference tell you/ what you are?" Is, Is Not will leave such questions spinning quietly in the mind. A bold new work from a poet of consequence. --Scott Neuffer, writer, poet, editor of trampset

| Publisher: | Chicken House/Scholastic | |

| Genre: | People & Places, General (see also headings under Social Themes), Europe, Family, General, Military & Wars, Legends, Myths, Fables, Juvenile Fiction, Historical | |

| ISBN: | 9781338353853 | |

| Pub Date: | April 2019 | |

| Price: | $17.99 |

| Starred | Children's & Young Adult |

by Lucy Strange

For 12-year-old Pet, normal is "living in a lighthouse" with her Pa, sister Mags and German-born mother, Mutti. But the start of World War II, with Hitler's army "surging up through France," is not an easy time to live in England and have a mother from Germany. Insults are hurled and Mutti is blamed for acts of sabotage in the nearby village. When "a package of information and drawings" is "intercepted... on its way to Germany," Mutti is taken away to live in an internment camp with other "enemy aliens." Mags convinces Pet they should "find out who the real spy is," and their first guess is the "nasty old" recluse living on the nearby south cliff, Spooky Joe. But before they can do much investigating, Mags's odd behavior--she's been getting into fistfights with Kipper Briggs and sneaking around with "handsome Michael Baron"--causes a rift between the sisters. Pet feels her entire family slipping away, and it falls to her to be brave enough to make sense of a very complicated world.

Lucy Strange's (The Secret of Nightingale Wood) second middle-grade work features elegant prose and an enchanting protagonist. Pet is earnest and unwavering, and the "small, mousy, and unimportant" girl at the beginning of the story is quite different from the strong young woman who emerges by the end. Her kinship with the Daughters of Stone--mythical girls who sacrificed themselves for the safe return of their fishermen fathers--lends a timeless, haunting quality to the story, and endows it with the weight of legend. The message that everyday friends, "people from church, the village shopkeepers and fishermen," can easily turn into an angry, frightened mob is especially timely. This haunting, historical novel is sure to touch young readers' hearts. --Lynn Becker, blogger and host of Book Talk, a monthly online discussion of children's books for SCBWI

| Publisher: | Candlewick Press | |

| Genre: | Europe, Military & Wars, United States - 20th Century, History, Juvenile Nonfiction | |

| ISBN: | 9780763681531 | |

| Pub Date: | April 2019 | |

| Price: | $19.99 |

| Children's & Young Adult |

by Paul B. Janeczko

During World War II, U.S. military officers conceived of a "deception unit" that could assist in the war effort. The group used radio signals, recordings, inflatable prop military vehicles and other special effects to mimic the movements and actions of other groups. The men in the unit risked their lives to convince the Nazis of a larger presence, an alternate attack plan or simply to cover the retreat of a weary company while another was en route to take its place. Often staging their scenes near the front lines of the war, the men--actors, camouflage experts, sound engineers, painters and set designers among them--knew their missions were dangerous and that the cost of discovery would be devastating; they "were ordered to say nothing of their exploits and accomplishments for fifty years."

Secret Soldiers by Paul B. Janeczko (Double Cross: Deception Techniques in War) brings to light a little-known element of the Allied war effort: the U.S. Twenty-Third Special Troops and the unusual yet critical part it played in World War II. Whether attempting to trick the Nazis about the details of the impending D-Day invasion or masquerading as another troop to allow it to slip into an alternate position, the missions of the Twenty-Third were varied and high tension. Janeczko intersperses his narrative with photographs and mini biographies of the men in the unit. Secret Soldiers is enlightening and intriguing, a must-read for young military buffs. --Kyla Paterno, former children's and YA book buyer

| Publisher: | Cameron Kids | |

| Genre: | Pets, Animals, United States, Dogs, Biographical, Juvenile Fiction | |

| ISBN: | 9781944903589 | |

| Pub Date: | April 2019 | |

| Price: | $16.95 |

| Children's & Young Adult |

by Barbara Lowell, illust. by Dan Andreasen

"Sparky's dog, Spike, is a white dog with black spots. He's the wildest and smartest dog ever." What makes Spike so smart? Well, he can ring a doorbell, fetch a potato and eat things like screws and handkerchiefs to no ill effect.

The other love of young Sparky's life is comics, and he dreams of becoming a cartoonist. Persevering through his insecurities, he develops a talent, and soon the kids at school are clustering around him and requesting illustrations.

One day, Sparky realizes that the newspaper comic strip Ripley's Believe It or Not! offers a way to merge his two loves: he draws a picture of Spike on a letter heralding the dog's sense of gastronomic adventure and submits it to the strip. Finally, the Sunday paper runs Sparky's illustration, supplemented with the caption "A hunting dog that eats pins, tacks, screws and razor blades is owned by C.F. Schulz, St. Paul, Minn.," and a storied career is unassumingly launched.

Sparky & Spike: Charles Schulz and the Wildest, Smartest Dog Ever features Barbara Lowell's borderline "See Spot run"-simple sentences and Dan Andreasen's Tintin-reminiscent illustrations, some in panel format, many on pixelated backgrounds, Sunday funnies-style. These beguiling nods to an earlier era may elude young readers, who needn't register these winks in order to be charmed by this double homage: to a boy's dog, and to a boy who grew up to become the beloved illustrator of the comic strip Peanuts, which starred a certain other white pooch with black spots. --Nell Beram, freelance writer and YA author