|

| photo: Liz Norton |

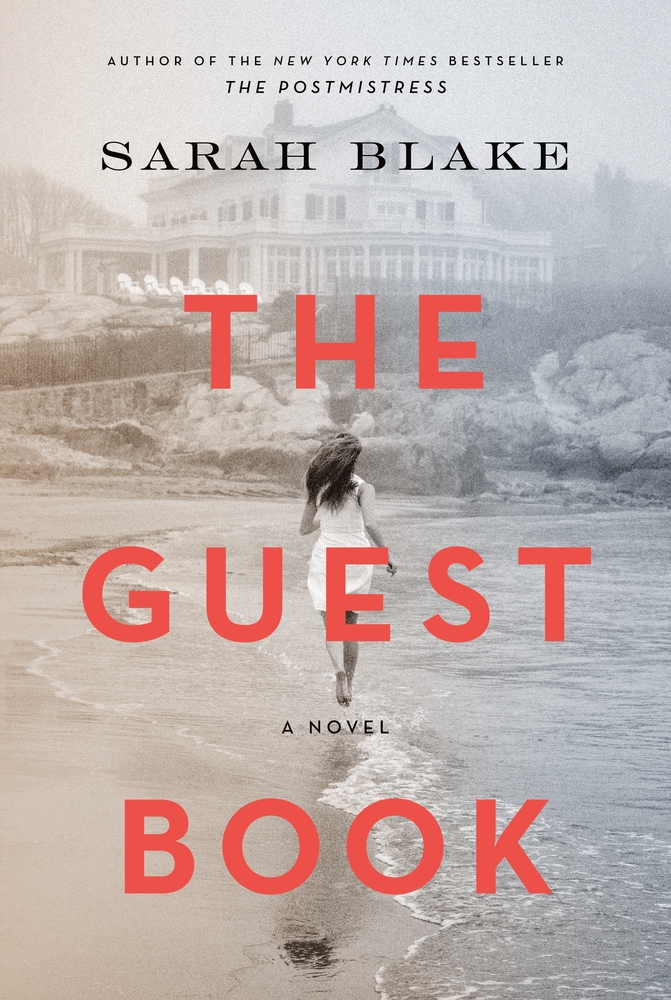

Booksellers across the country have chosen The Guest Book (Flatiron Books, May 7), the new multigenerational novel by Sarah Blake, as their number-one pick for the May Indie Next List.

The Guest Book witnesses a changing America across three generations of the Miltons as they pass through the family's lavish estate on an island in Maine. After her mother's death, historian Evie looks more closely at the longstanding myths that undergird the Milton family dynasty, a personal journey that yields a wealth of secrets. As the book follows the Miltons from 1936 to 1959 to the present day, readers discover a family--and a country--that buries the secrets of the past until the present brings a reckoning, demonstrating the subterranean currents of class and power that have shaped America.

Blake is the author of two other novels: Grange House (Picador) and 2010 New York Times bestseller The Postmistress (Amy Einhorn Books/Putnam). Blake taught high school and college English in Colorado and New York and has taught fiction workshops at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts; the Writer's Center in Bethesda, Maryland; the University of Maryland; and George Washington University. She lives in Washington, D.C., with her husband, the poet Joshua Weiner, and their two sons.

Here, we talk to Blake about her latest novel, which received starred reviews in Booklist, Kirkus, and Library Journal.

How did you get the idea for this book?

I always, always wanted to write a big, juicy multigenerational novel. I grew up loving The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende, Virginia Woolf's The Years, and The Forsyte Saga, [and reading about] the ways in which families evolve by both keeping secrets and telling secrets; I wanted to wade into that. When I started writing this book, it was 2009 and Obama had just been sworn in, and I was really affected by his speech in Philadelphia on the campaign trail in which he quoted Faulkner. In the speech, he was trying to address issues of race in the presidential campaign and in the country, and he said, "The past isn't dead. It isn't even past."

At the time, it seemed to me that the conversation around race was really shifting; for the first time in my adult life, it seemed like, black and white people were having conversations about the way in which our racial past was inflecting the present, and it was something I had not been privy to. It was incredibly exciting, so I wanted to enter that and really think about my own place in terms of the history of this country, as a white woman and a sort of old-money WASP. When the time came to start this novel, those two things were very much in place. I thought that writing a family history might be a way to think about this country's history and the ways that we echo and repeat the past when we claim not to know things, or when we "forget" what has happened. That's the terrain where I started.

Did the form or focus of this book change as you wrote it over this past decade, which has been exceedingly politically tumultuous?

It's incredible what has happened. In fact, I handed it in last summer, so it was written basically from 2010 to 2018, and it seemed like that conversation just kept getting bigger and bigger and broader and broader. When Trump was elected, it became inescapable to see the ways in which we were inflecting our histories over and over and over again. We keep repeating the past, in so many ways. One of the things I wanted to do in writing this story was to show how who we are and who we were are always going on at the same time, which seems to me the best way to think about this country's racial past and present. I wanted to write the book so that the story alternated back and forth in time periods, so that the '30s, the '50s, and the present were carrying on side by side.

Another thing that was instrumental for me in writing this was when my family and I moved to Berlin. I was really affected by how that city has externalized its history. There is a project there called the "stumbling stones," where paving stones are inscribed with written commemorations of the tragedies that happened there. It feels like with American memory, we keep passing on these ideas of race and class and who we are in the structure without externalizing them. That is what gave me the idea of setting the story in one place that would be the thing to bind and define who this family was, and so was also the place they would constantly return to. In this one place, we see what happens when memory is set loose and how that can create its own kind of reckoning.

Do you feel that great historical fiction can help portray the kinds of essential truths that the mere recalling of facts cannot?

Do you feel that great historical fiction can help portray the kinds of essential truths that the mere recalling of facts cannot?

Yes, absolutely. I think that is one of the great powers of literature: you take the facts, or the credible world, the real, and you make it true in a way that allows you to see past facts, to see around facts, to understand in a way that brings that world to life and allows for greater insight. There's power there, for sure. One of things that I realized by the end of this book was the ways in which historical fiction can be incredibly subversive. If the writer has created a credible historical world, reading a good historical novel will force you to really ask yourself, who would you have been in that past? The pleasure of historical fiction is that you get transported, but the sneaky subversion of it is that you are also brought face to face with that idea of who you would have been, which begs the question, who are you now?

You mentioned having an old money, WASPy background. How did having that sort of past influence what you were writing and the lifestyle you were depicting?

I come from the kind of family in which there has always been an implicit sense of our own history, of being upstanding and noble and right. I was really ready to take a look at all the ways in which the structures of this country were set up and the ways in which my family was part of that. I wanted to take on my own place in the structural injustices of this country and look at this notion that we carry inside of us all the voices of the past, that we just repeat the words of our parents and grandparents, often without hearing or knowing it. There's a sense of just passing this stuff on and on and on without seeing it, even when you think you do see, as with the character of Evie. You can say that you see, but at the same time, you can keep on sounding and behaving just like your grandmother. That goes back to the idea that when memory isn't externalized, when it isn't made physical, this is the way it is carried on.

In writing The Guest Book, did you research the different time periods you were writing about (the '30s, the '50s, and today)?

Oh yes, I did a lot of research. The Postmistress, the novel I did before this, was a World War II novel so I had spent quite a lot of time researching the '40s and before that the late '30s. For this one, I wanted to amplify that even more so I spent a lot of time researching the '30s and thinking about, what was the level of resistance, especially in the early '30s, to the Nazi takeover as it was moving? In some ways it was moving unbelievably quickly, and in the other ways it was moving very, very slowly, so that people could think, this is not that bad, he's doing this for this or that reason. I was very interested in the time before it all exploded, before the Final Solution, before Kristallnacht, those years when history was moving but the people inside it couldn't see that this was a historical moment and a catastrophe. And with 1959, it was the same reason I was interested in setting this in a period right before things broke open on the surface, into the '60s and the civil rights movement. In '59, everything was incipient; it was the year when all kinds of forces were at work, but they still remained under the surface. That was interesting to me, so I spent a lot of time there.

In the acknowledgements, you note that the poet Claudia Rankine is a longtime friend and was a reader of this book as you wrote over the years. Do you feel like her involvement helped clarify your message?

Claudia and I have been friends for a very long time, but the conversation specifically around being white and being black in this country is one we've been having for decades, especially this idea of who we are in the moment as a white person or a black person as it is connected to the history that we carry with us, and the idea that there might be a historical self and then a self that imagines itself separate from history. She and I talk all the time about these issues; it seems like the most important conversation you can have. So yes, along with my own reading, I feel like I've talked my way toward whatever understanding I have of these issues very much through these conversations with her. --Liz Button

A Q&A With Sarah Blake, May's #1 Indie Next List Pick

Do you feel that great historical fiction can help portray the kinds of essential truths that the mere recalling of facts cannot?

Do you feel that great historical fiction can help portray the kinds of essential truths that the mere recalling of facts cannot?