.jpg) |

| photo: Tom Hines |

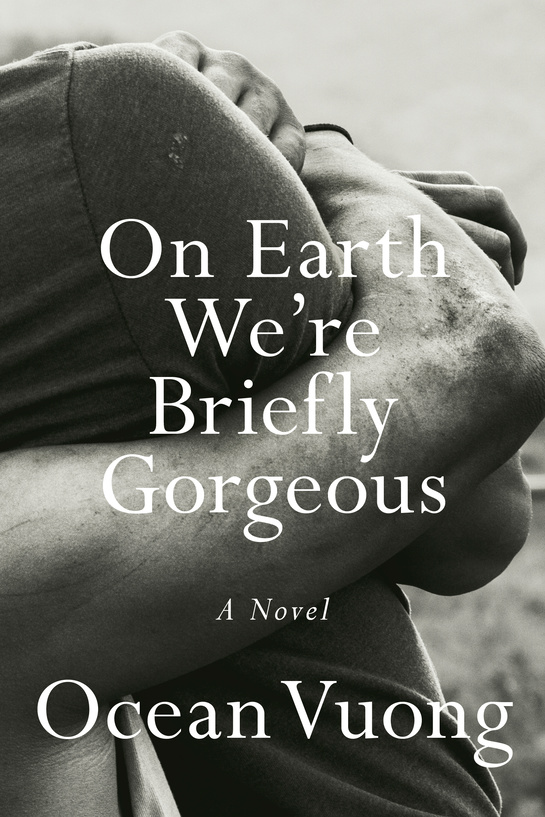

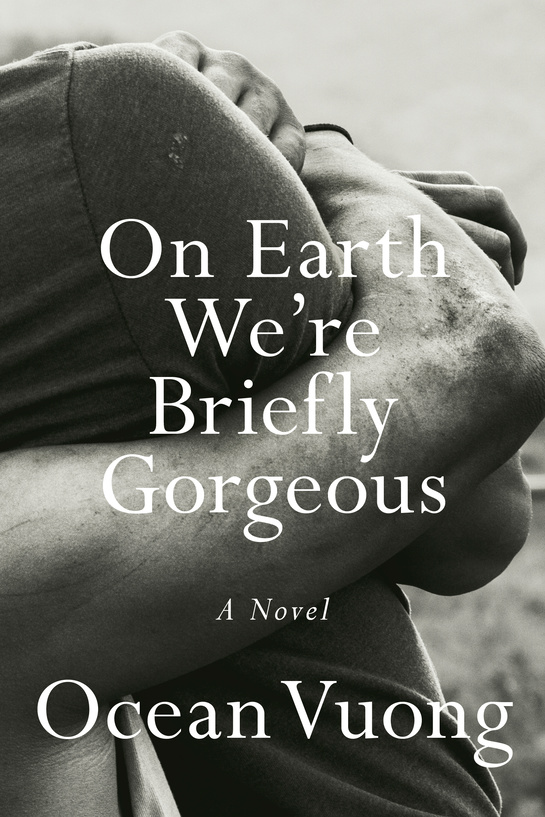

Booksellers across the nation have chosen On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, the debut novel by poet Ocean Vuong (Penguin Press, June 4), as their number-one pick for the June Indie Next List.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, which received starred reviews in Kirkus, Booklist, and Library Journal, is a portrait of a family, first love, and the power of storytelling and an exploration of the American stories of race, class, masculinity, immigration, as well as of addiction, violence, and trauma.

The novel's format is a letter from a son to a mother who cannot read, in which 20-something Little Dog unearths his family's history that began before he was born in Vietnam. On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous is about the power to tell one's own story and, on the other end, the tragedy of silence.

Vuong is the author of the critically acclaimed poetry collection Night Sky With Exit Wounds, winner of the Whiting Award and the T.S. Eliot Prize. His writing has been featured in The Atlantic, Harper's, The Nation, New Republic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times. Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he currently lives in Northampton, Massachusetts, where he serves as an assistant professor in the MFA Program for Poets and Writers at Umass-Amherst.

Here, the poet discusses his debut novel.

How did you come up with the idea for this book?

It was an experiment. I wrote a book of poems [Night Sky With Exit Wounds] and, well, with any book, you have a certain amount of questions you ask. In Night Sky I ask mostly, what is an American identity when it has to reckon with American violence? That violence is a part of this country's self-knowledge and we don't have to sugarcoat it. We can look at it as the result of why we are who we are and why we're here--violence as a means of self-knowledge.

So all of a sudden you write a book of poems and it takes off in ways you don't imagine, and all your peers and editors and friends say, well, alright, now you have to do another one and you've got to do something different. That's our culture--that's the capitalistic anxiety, to produce a fresh new product, to do a 180 now. But I didn't feel like I was done asking about American identity, particularly as it relates to the immigrant and refugee experience. And I thought, well, I don't know if 85 pages of poems in paperback can really contain or solve these questions, so what if I took the same questions into a different form, the novel? What would happen? And that was the experiment. And I told myself, if nothing happens, if I'm just repeating myself, I'll put it away and go back to poems. So it was an experiment. It wasn't as courageous or bold as you would like the origin story of a novel to be.

What was the writing process like for this novel compared to your process for writing poems?

It was drastically different, mostly because of the circumstances of our world at the time. I was teaching undergrads at NYU while I was writing this book and I wrote it by hand, the first draft at least--it would go through 12 drafts. Meanwhile, the election cycle was happening, all of which would lead to Trump's election, and every day there was a new nightmare in the news and I would have to show up to these students and convince them that writing mattered and sometimes I couldn't do it. Sometimes I felt like I didn't know if it mattered myself, so I would go home and write this book and for some reason I was so... scared, is just the frank word of it all, because we were so scared at the time. I cleared out the closet in my apartment, I put a lamp in there, and I closed the door (the irony is not lost on me, I literally went back in the closet, but that was how it was done). When I went in there, everything fell away, the world fell away, and I could go back in time, go back in 2003 and 2004 (a lot of this book takes place in the Bush era). It was kind of like this cockpit I went into every day. And that was the first time I understood what a lot of writers say. A lot of times we say writing is my refuge, and we say that sometimes in an abstract sense, but for the first time in my life it was a true refuge. At the end of the day I looked forward to closing the closet door, holding the notebook, turning on the lamp, making a cup of tea, and crouching down in there, sliding back into that world. I really escaped into the past. It was like a fever dream.

So do you feel like you were able to convince yourself of what you were trying to convince your students of, that writing matters?

So do you feel like you were able to convince yourself of what you were trying to convince your students of, that writing matters?

That was the inquiry. Yes, I don't know if I'll ever answer that question, but that was sort of the allegory that I fell on. Because Little Dog is a son writing to a mother who can't read, there is an innate futility in the act, and the innate crisis that I was negotiating with my students was, does this matter? When our brothers and sisters and our friends are being deported, when children are being held prisoner at the border, when we're still bombing the Middle East, does this matter? And I suppose the whole book attempts an architecture to explore that. I wouldn't say the whole book answers that, I don't know if I answered it myself, but parallel to that question, even if a mother can't read, does it matter to say it? Does it mean anything to put the sentence down as an object and put the thought inside the sentence? Ultimately, I would say yes, but to what extent that it satisfies us, I'm not sure.

How did you decide on the format of the narrator, Little Dog, writing a letter to his mother?

I struggled with the form. There were a lot of dead ends, but in the end I was reading two books that really solidified it. I live in New England and teach at UMass, and Herman Melville lived about an hour away so I visited his house--it's kind of the obligatory pilgrimage--and I figured while I'm living up here I might as well reread Moby-Dick. People rarely think about this but that's an autobiographical novel. It's almost absurd to think because it's so ecstatic and eclectic and wild, but Herman Melville lived that life, he lived on the ship, he hunted the whales, he did all that, and on top of that, what I loved about that book was that the novel became a method of essayistic exploration. In other words, it allowed every detour imaginable; it had chapters on how to identify whale humps, whole chapters on how to harvest spermaceti. It was an essay, a manual, a novel, a thriller. And it was interesting, that he as a writer never had to make those decisions; he said I'm going to go for the jugular, I'm going to put everything in this book. I knew this was what I was hoping for, but I also knew I didn't want to write 600 pages. So I had to find the form to do it.

And then I fell on this little book by Franz Kafka; it's actually a letter to his father published as a book. It's 60 pages, called Dearest Father, but it was just a private letter that was published later on and he never sent, so that's also like Little Dog. For Kafka it was that he just didn't have the audacity to confront his father who was such a large-looming figure to him. I thought, my goodness, what an incredible concept: writing a letter that can't be sent. And then in the letter, he detoured, he went on philosophical tangents--he made his own testimony of why he chose to be a writer instead of lawyer like his father wanted. Kafka's letter was a method of inquiry, and I thought, there it is. The added power to that is knowing that to read this novel you have to eavesdrop on an Asian American speaking to another Asian American and that concept was so alluring and powerful to me: an American story in which whiteness has to sort of eavesdrop on the dialogue, to be on the sidelines. That felt very subversive and powerful to me as a way to negotiate the western canon we are always inundated by.

Why did you choose to deeply explore the background stories of the women in Little Dog's life, his mother and grandmother?

I think that no matter who we are in America, if we ask about our grandparents, we arrive at a lineage of war. Whether they were in the Holocaust, World War II, the Korean War, eventually we arrive at a geopolitical rupture. This is true for people of color, but especially for white folks, because we are told that whiteness is sort of nothing, it's self-generating, but in fact if we ask where do we come from, what happened in Europe, we find war, we find bombings. We arrive at a very similar space, and we find that American identity is made of war, whether it is on this soil or overseas. And what we rarely see as worthy of literature with a capital L are the stories of the women who lived in the aftermath, the women who had to live and bear it and clean up after the men who have PTSD, who are violent, literally clean up the countries that are decimated. I wanted these women, working class/borderline poverty women of color and white folks, to be central in a book and to make a statement that these lives are inspiring, that they are worthy of literature with a capital L.

Who are some poets or other writers who have influenced you or whose work you admire?

Emily Dickinson, Natalie Diaz, Eduardo C. Corral, Richard Siken. There are so many: Lorca, Maggie Nelson, Claudia Rankine. I love hybrid texts, Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red, Marilynne Robinson's Gilead, Marguerite Duras' The Lover, Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, which is an incredible epic about American failure. Up until then no author had really reckoned with what it means for the American dream to fall apart, and he was one of the first. I also loved what that book did with form and fracture and fragmentation. --Liz Button

A Q&A With Ocean Vuong, Author of June's #1 Indie Next List Pick

.jpg)

So do you feel like you were able to convince yourself of what you were trying to convince your students of, that writing matters?

So do you feel like you were able to convince yourself of what you were trying to convince your students of, that writing matters?