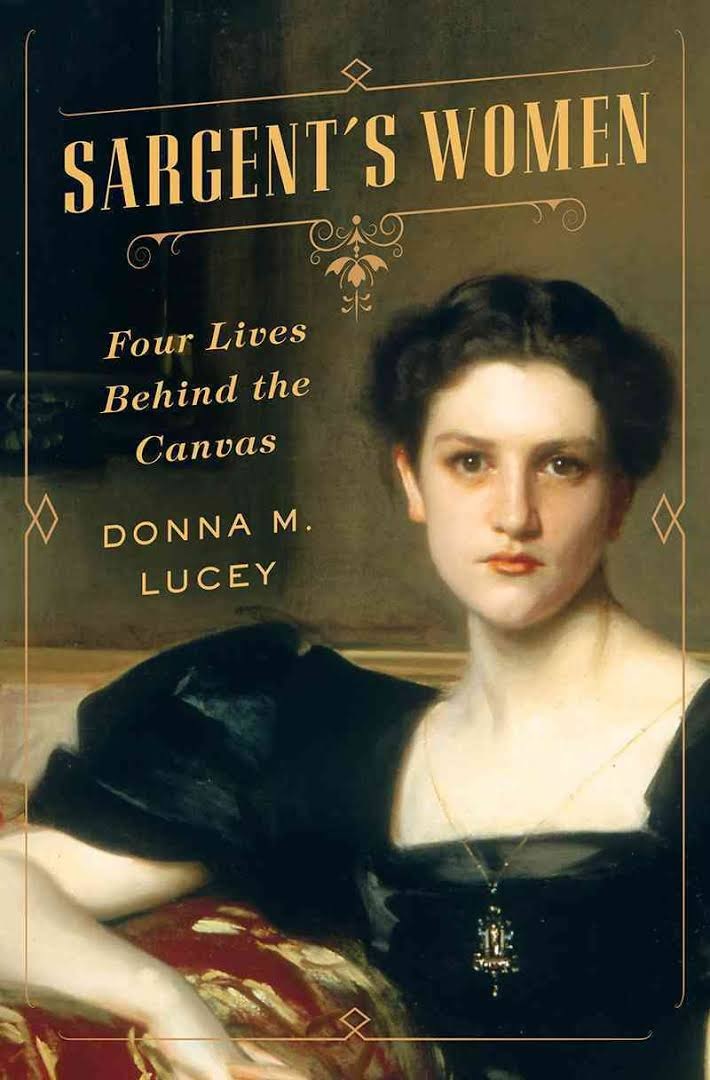

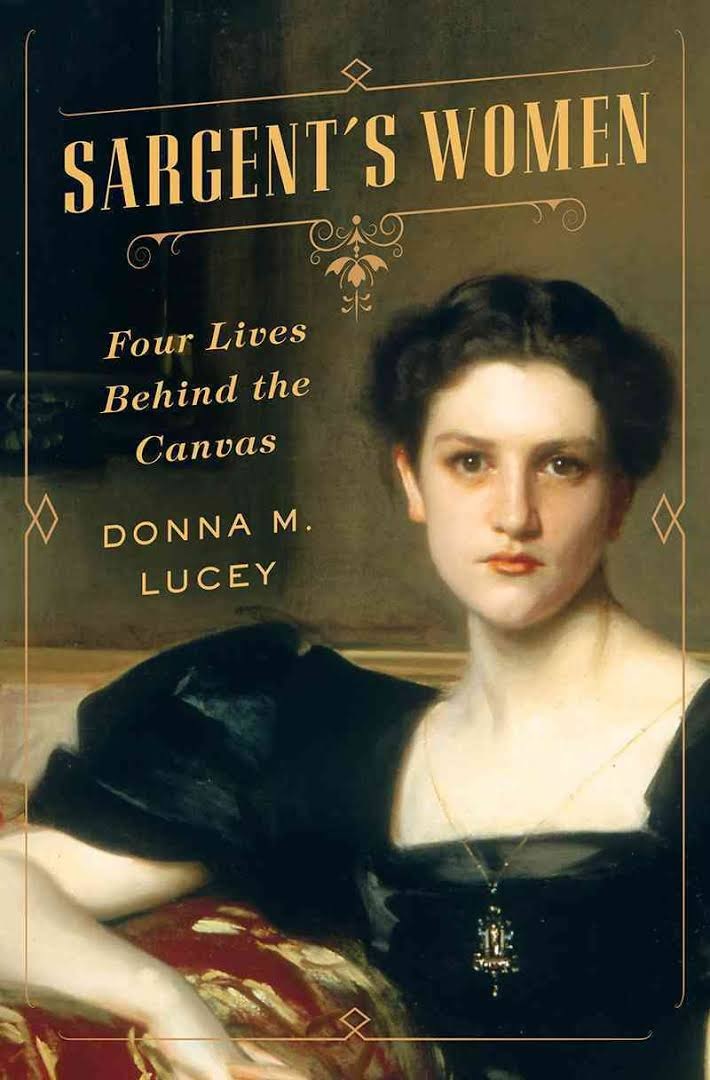

The son of nomadic expatriate Americans on the fringes of high society, John Singer Sargent settled in England in the late 19th century where he remarkably cranked out more than 900 portraits and thousands of landscapes--to a largely indifferent artistic critical reception. The rich, however, afforded him significant patronage. Four of these portraits completed in the 1890s feature American women of great wealth and pedigree. For eight years historian Donna M. Lucey (Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age) researched the letters, journals and archives of these formidable women and their families (as she notes in an introduction, "a bit like Gilded Age porn") to flesh out the stories behind their often eccentric and accomplished lives. Sargent's Women has little to say about the prolific artist but a good deal to say about life among affluent women with brains and talents beyond the Victorian strictures of their time.

The son of nomadic expatriate Americans on the fringes of high society, John Singer Sargent settled in England in the late 19th century where he remarkably cranked out more than 900 portraits and thousands of landscapes--to a largely indifferent artistic critical reception. The rich, however, afforded him significant patronage. Four of these portraits completed in the 1890s feature American women of great wealth and pedigree. For eight years historian Donna M. Lucey (Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age) researched the letters, journals and archives of these formidable women and their families (as she notes in an introduction, "a bit like Gilded Age porn") to flesh out the stories behind their often eccentric and accomplished lives. Sargent's Women has little to say about the prolific artist but a good deal to say about life among affluent women with brains and talents beyond the Victorian strictures of their time.

As Lucey discovers in her research, the lives of these moneyed women were not all mansions, servants and exotic travel. Sargent's enigmatic portrait of Elsie Palmer shows a face "steely and cold... all hard edges. Humorless... otherworldly"--what Virginia Woolf described as "marmorial and mute." Yet this daughter of a Colorado mining tycoon lived into her 80s, caring in due course for a sickly mother, an overbearing and eventually quadriplegic father, a consumptive sister and a suicidal husband.

Sargent painted the beautiful young Boston heiress Sally Fairchild with a translucent veil alluringly hiding her face, but it was her less attractive sister Lucia who went on to some fame as an artist and miniaturist. The Fairchild family, nevertheless, had its curses. They lost their fortune in the Panic of 1893. Three out of five of Sally's brothers committed suicide. Lucia, who wrote of her life that it was meant to "eat, drink, paint, and be merry," died of pneumonia at age 52.

Elizabeth Chanler was raised in the Hudson River estate and Upper West Side mansion funded by her family's vast Astor fortune, "an unbeatable combination of blue blood and greenbacks." She and her siblings grew up daredevils in a world more "Lord of the Flies than Peter Pan's Neverland." Sargent's portrait of her traveled seasonally between the two palaces "like a migrating bird." The Astor genes, however, brought not only wealth, but also a risk of descent into madness--a fate avoided by Chanler.

Sargent's Women concludes with perhaps the most famous of these heiresses, Isabella Stewart Gardner--who was the subject of two Sargent portraits and was his longest and most significant benefactor. She had the money and taste to amass a significant art collection, which now sits in her eponymous museum among Boston's Fens. With thousands of paintings, drawings, sculptures, textiles, ceramics, books, glass, furniture and assorted historical bric-a-brac, her collection was one of a kind. Rather than focusing on Sargent, Lucey wisely concentrates her attention on these women who epitomized their class and times. Sargent only painted them. --Bruce Jacobs founding partner, Watermark Books & Cafe, Wichita, Kan.

Shelf Talker: Lucey's carefully researched and illustrated history of four women immortalized in Sargent portraits creates a vivid picture of the Gilded Age.

IPC.0204.S3.INDIEPRESSMONTHCONTEST.gif)

Longtime bookseller Andy Laties and his wife, Rebecca Migdal, a puppeteer, author and illustrator, are opening

Longtime bookseller Andy Laties and his wife, Rebecca Migdal, a puppeteer, author and illustrator, are opening

Dog-Eared Books, Campbellsville, Ky., a used bookstore that has sold some new books, is closing at the end of July.

Dog-Eared Books, Campbellsville, Ky., a used bookstore that has sold some new books, is closing at the end of July.

On Thursday, the second e-newsletter edition of the American Booksellers Association's Kids' Next List was delivered to more than a third of a million of the country's best book readers. The second part of the summer newsletter (the

On Thursday, the second e-newsletter edition of the American Booksellers Association's Kids' Next List was delivered to more than a third of a million of the country's best book readers. The second part of the summer newsletter (the IPC.0211.T4.INDIEPRESSMONTH.gif)

Neighborhood Reads

Neighborhood Reads Congratulations to the

Congratulations to the  The Subtle Body Coloring Book: Learn Energetic Anatomy--from the Chakras to the Meridians and More

The Subtle Body Coloring Book: Learn Energetic Anatomy--from the Chakras to the Meridians and More A first look

A first look The son of nomadic expatriate Americans on the fringes of high society, John Singer Sargent settled in England in the late 19th century where he remarkably cranked out more than 900 portraits and thousands of landscapes--to a largely indifferent artistic critical reception. The rich, however, afforded him significant patronage. Four of these portraits completed in the 1890s feature American women of great wealth and pedigree. For eight years historian Donna M. Lucey (Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age) researched the letters, journals and archives of these formidable women and their families (as she notes in an introduction, "a bit like Gilded Age porn") to flesh out the stories behind their often eccentric and accomplished lives. Sargent's Women has little to say about the prolific artist but a good deal to say about life among affluent women with brains and talents beyond the Victorian strictures of their time.

The son of nomadic expatriate Americans on the fringes of high society, John Singer Sargent settled in England in the late 19th century where he remarkably cranked out more than 900 portraits and thousands of landscapes--to a largely indifferent artistic critical reception. The rich, however, afforded him significant patronage. Four of these portraits completed in the 1890s feature American women of great wealth and pedigree. For eight years historian Donna M. Lucey (Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age) researched the letters, journals and archives of these formidable women and their families (as she notes in an introduction, "a bit like Gilded Age porn") to flesh out the stories behind their often eccentric and accomplished lives. Sargent's Women has little to say about the prolific artist but a good deal to say about life among affluent women with brains and talents beyond the Victorian strictures of their time.