|

Kevin Noble Maillard

(photo: Chris Owyoung) |

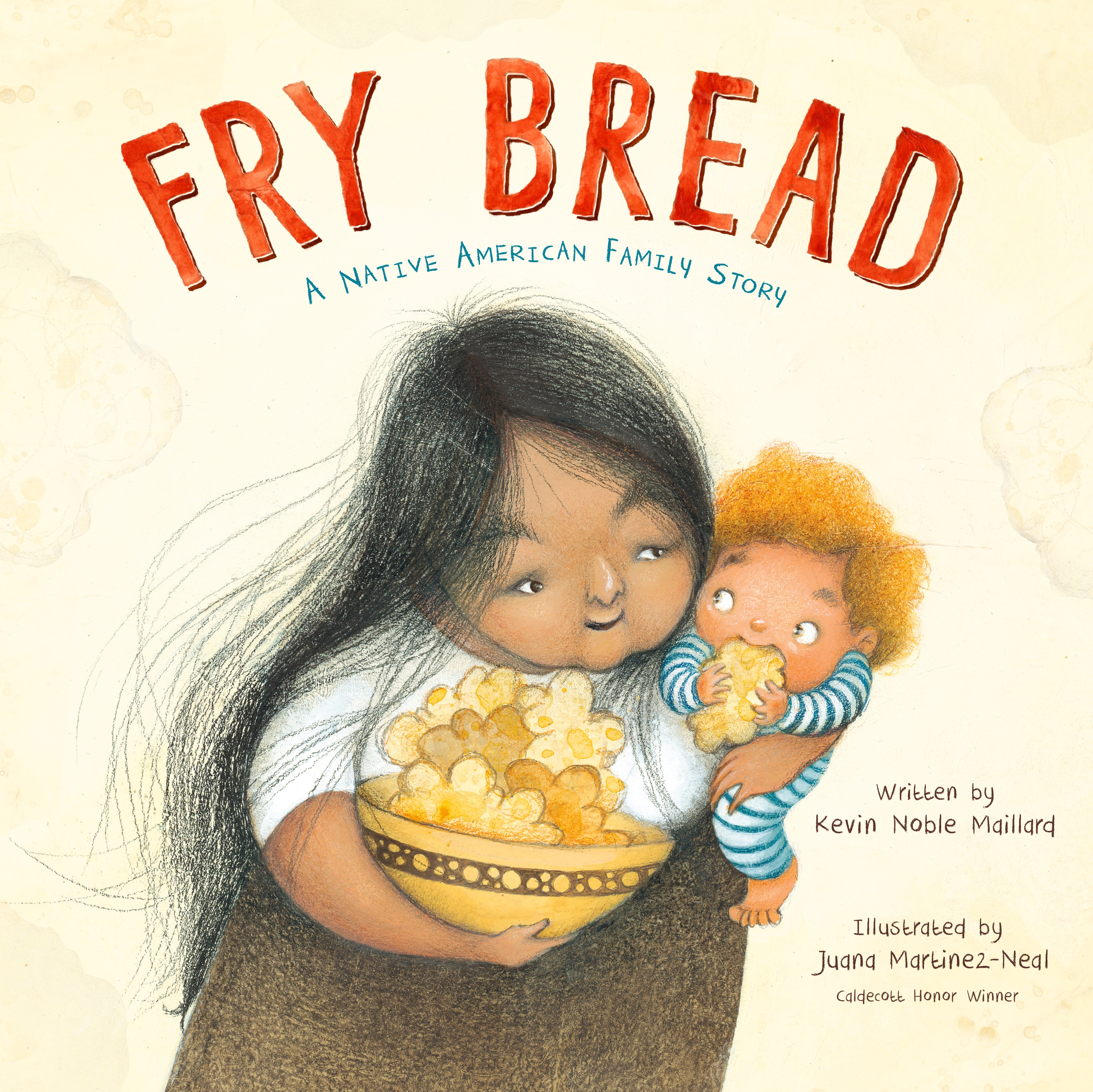

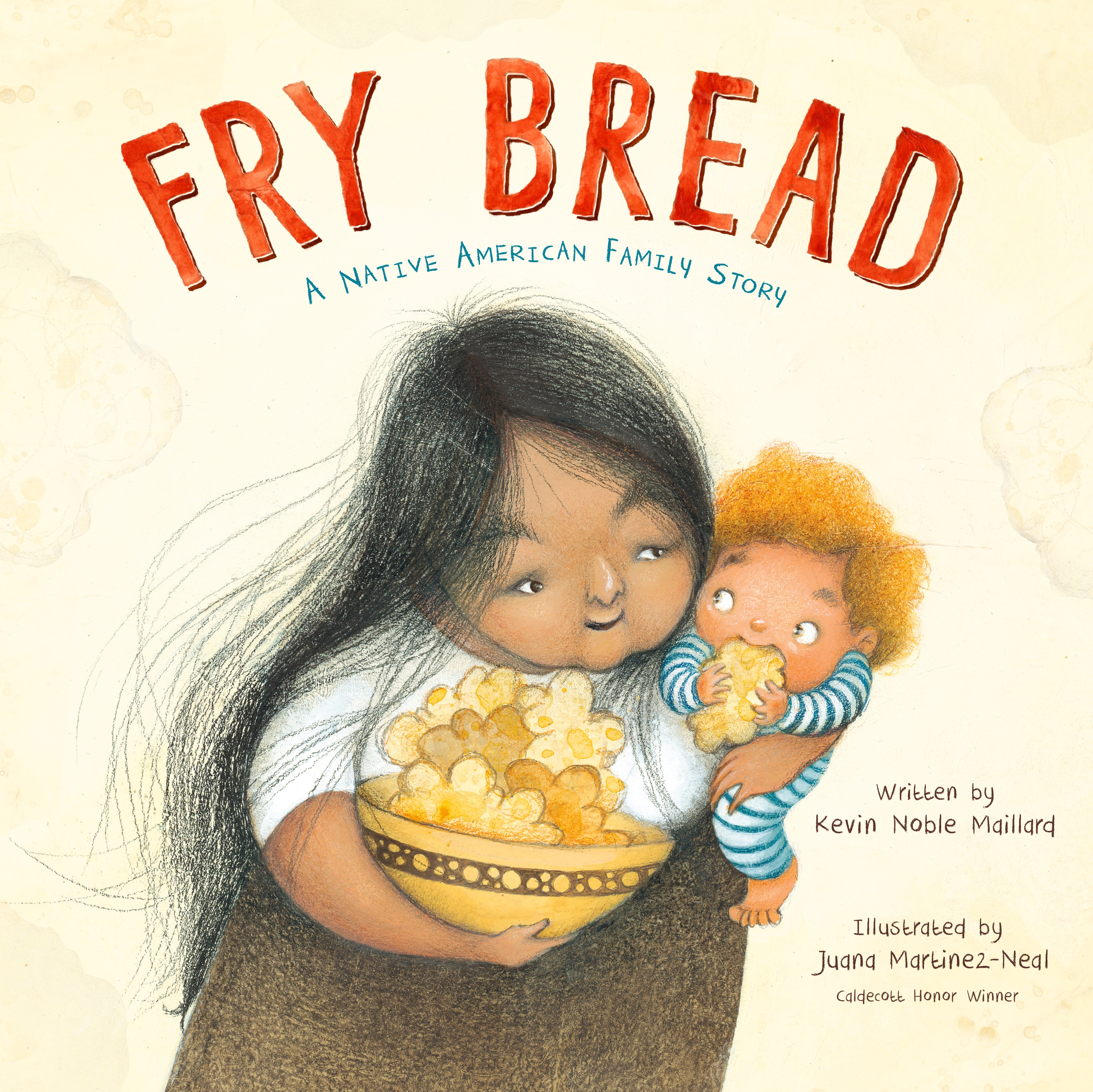

Last week, Kevin Noble Maillard won the Robert F. Sibert Medal for "the most distinguished informational book published in the United States in English" for his picture book Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story, illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal and published by Roaring Brook Press.

Congratulations! Fry Bread won the Sibert Medal, and it is also one of the Honor titles of the American Indian Youth Literature Awards, chosen by the American Indian Library Association (AILA). How are you feeling?

Exceedingly great, because these are the first professional or achievement awards I've ever won in my life, if you don't count my college dean's list or the Tulsa, Oklahoma, Fishing Derby.

Fry Bread is your first children's book; what made you want to write for children?

Yes, this is my first picture book. I wanted to write a book for my own children, and maybe some other Native kids that normally don't see themselves in books. When my oldest child was a baby, I was searching for board books to read to him and I kept coming up empty-handed. There were probably three titles out there that were modern stories written by Native folks. All the rest were historical Thanksgiving stories written by white people. I was so appalled and, frankly, mad, that I decided to write my own.

These books have such a strong impact on how we see ourselves and how we see others. Representation in children's books is analogous to representation in film and television for adults. Who is being seen and who is being pushed aside and, most importantly, who is telling the story? For Native people, the story is usually told by white people and the narrative is not right: amicable relations, land sharing, friendships. It's like staring inside a mirror and asking, "Who's the fairest of them all?" then changing every single answer to "manifest destiny!" And that's just really not the honest truth, or anything remotely close to it.

This book has two distinct sections: one that is lushly illustrated and feels experiential, the other more teaching and text oriented. Do you think this format helped make Fry Bread a Sibert pick? Are there other aspects of Fry Bread that you think made it "the most distinguished informational book published in English" in 2019?

I'm a law professor during the day, so I'm a researcher by trade. I also write a lot for the New York Times, so I'm used to translating dense information into approachable text. Writing the back matter for me was like writing academic scholarship with footnotes, a bibliography and peer review. So much peer review. I really think there were at least 40 edits to the back matter, and I've been through some really extensive editing processes as a professor and journalist. I went through so many rounds with the editors... and we would debate, debate and debate some more about the appropriate word to use. Most people don't know this, but there are so many more people than the author and illustrator behind the book scenes. We had two editors, two readers and three fact checkers. You know how the credits roll at the end of a film--even a short one--and there are hundreds of names of people that worked on the product? That's what this book was, and there were so many people contributing to the substantive content of the pages. I did a Ph.D. in political theory in addition to my law degree, and this back and forth was really familiar to me, like an interdisciplinary dissertation committee.

Our outside reader presented some incredibly difficult questions that really forced me to think through each section of the back matter. All of these editors and readers pushed me to the next level, like the smiliest but super-demanding personal trainers. I'm pretty sure [editor] Connie Hsu takes notes from the Mickey character in Rocky. I'd get an e-mail every few days that would say something like, "Should we add...." But for months! This was such a dialectical process that I felt I deserved tenure when we finally finished it.

Has your relationship with Fry Bread the book and fry bread the food changed from the beginnings of creating this book to receiving this award?

Has your relationship with Fry Bread the book and fry bread the food changed from the beginnings of creating this book to receiving this award?

Not at all. I'm still the fry bread lady in my family. It's not going to cook itself.

But the bonus side of it now is that I can feel more comfortable being an expert on the topic, because I always used to feel that my recipe was too different.

How does it feel to have your work recognized by the American Indian Library Association?

Amazing. I'm very conscious of inside-community opinion, especially with Native readers. It's hard to please everyone, but with Native topics, there are a lot of ways that things can be misrepresented. Having a community of Indigenous educators who love books, understand Native history and, most of all, are picky about fry bread recognize and celebrate the book feels pretty darn great.

Is there anything else you'd like to tell Shelf Awareness readers?

I still think about being in second grade in Tulsa, and the teacher calling Marsha Berryhill's name for "Best Story Award" instead of mine. I'm sure my face looked like a side-eye emoji. I remember thinking that one day I would write something that would get all the teachers' attention. It took about 40 years, but I succeeded. --Siân Gaetano, children's and YA editor, Shelf Awareness

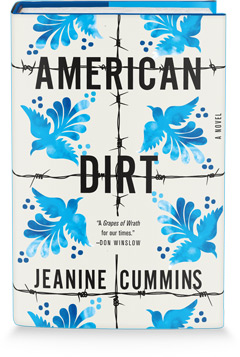

Yesterday #DignidadLiteraria and @PresenteOrg--among the major critics of American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins (Flatiron Books) and a lack of diversity in publishing--announced on Twitter that they had met with the leadership of Macmillan, parent company of Flatiron, and secured a commitment for Macmillan to "transform their publishing practices to include substantial increases in Latinx titles and staff, company wide." They added that Macmillan committed to "developing an action plan to address these objectives within 90 days" and that it will "regroup within 30 days with #DignidadLiteraria and other Latinx groups to assess progress."

Yesterday #DignidadLiteraria and @PresenteOrg--among the major critics of American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins (Flatiron Books) and a lack of diversity in publishing--announced on Twitter that they had met with the leadership of Macmillan, parent company of Flatiron, and secured a commitment for Macmillan to "transform their publishing practices to include substantial increases in Latinx titles and staff, company wide." They added that Macmillan committed to "developing an action plan to address these objectives within 90 days" and that it will "regroup within 30 days with #DignidadLiteraria and other Latinx groups to assess progress."

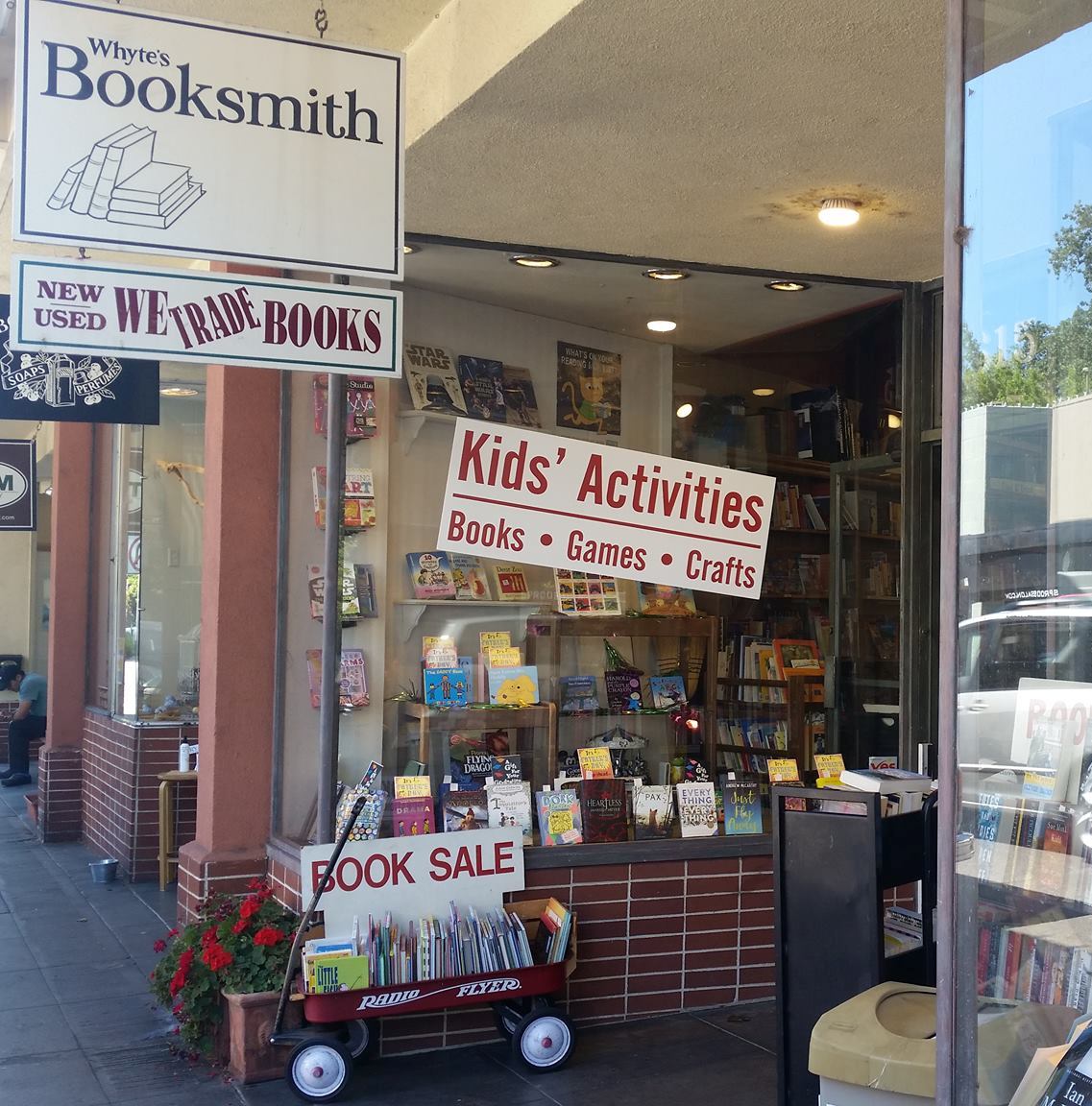

Whyte's Booksmith

Whyte's Booksmith

Has your relationship with Fry Bread the book and fry bread the food changed from the beginnings of creating this book to receiving this award?

Has your relationship with Fry Bread the book and fry bread the food changed from the beginnings of creating this book to receiving this award?

Noting that "we've got three different models here of how we've introduced food and beverages into the bookstore," Donna Paz Kaufman of

Noting that "we've got three different models here of how we've introduced food and beverages into the bookstore," Donna Paz Kaufman of

Debuting on this week's New York Times paperback nonfiction bestseller list at #14 is Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, which was released by Milkweed Editions in paperback five years ago (and in hardcover in 2013).

Debuting on this week's New York Times paperback nonfiction bestseller list at #14 is Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, which was released by Milkweed Editions in paperback five years ago (and in hardcover in 2013). At the beginning of January, more than 100 rare volumes were stolen from

At the beginning of January, more than 100 rare volumes were stolen from  Congratulations to

Congratulations to  Lights All Night Long

Lights All Night Long

Finalists have been named for the 25th annual Audie Awards, sponsored by the Audio Publishers Association. Winners of the awards will be announced at the Audie Awards Gala in New York City on March 2 that will be hosted by author and CBS Sunday Morning correspondent Mo Rocca. In addition, a lifetime achievement award will go to Stephen King.

Finalists have been named for the 25th annual Audie Awards, sponsored by the Audio Publishers Association. Winners of the awards will be announced at the Audie Awards Gala in New York City on March 2 that will be hosted by author and CBS Sunday Morning correspondent Mo Rocca. In addition, a lifetime achievement award will go to Stephen King. In this high-concept second novel, Margarita Montimore's (Asleep from Day) heroine experiences her life out of order in a smart, funny, time-hopping journey around the last four decades.

In this high-concept second novel, Margarita Montimore's (Asleep from Day) heroine experiences her life out of order in a smart, funny, time-hopping journey around the last four decades.