Whether dwelling in fairy lands (The Night Fairy) or medieval England, 1911 Baltimore (The Hired Girl) or 1860 London (Splendors and Glooms), former librarian and Newbery Medal winner (Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!: Voices from a Medieval Village) Laura Amy Schlitz is herself a "good master" of world building. Here, Schlitz shares with Shelf Awareness the surprisingly thrilling process she went through to write Amber & Clay (Candlewick Press, March 9, 2021).

Whether dwelling in fairy lands (The Night Fairy) or medieval England, 1911 Baltimore (The Hired Girl) or 1860 London (Splendors and Glooms), former librarian and Newbery Medal winner (Good Masters! Sweet Ladies!: Voices from a Medieval Village) Laura Amy Schlitz is herself a "good master" of world building. Here, Schlitz shares with Shelf Awareness the surprisingly thrilling process she went through to write Amber & Clay (Candlewick Press, March 9, 2021).

I've been trying to imagine all the ways Amber & Clay came to be. Inspiration?

More than 20 years ago, I wrote a play about Sokrates for my fourth graders. I put the scene from the Meno in my play: the scene where Sokrates asks an enslaved boy to solve a problem in geometry. That's when I began to wonder about that boy. What was it like for him to be put on the spot by "the wisest man in Athens"?

I spent years trying to think of a way to write about that boy--and Sokrates--for Candlewick. I began work about five years ago. When I read Bettany Hughes's fascinating book, The Hemlock Cup: Socrates, Athens, and the Search for the Good Life, I came across the "Little Bears," those girl-children who served Artemis at her sanctuary in Brauron. I'm drawn to bears and I loved the idea of these young girls serving the goddess as bears. I thought, "I've got to write about those girls!" But I already had my hero, the enslaved boy from Thessaly, and I couldn't think of any way he could meet up with one of the Bears. The Little Bears were almost certainly the daughters of aristocrats and a wellborn Athenian girl would have had no contact with boys. How could they meet?

Here comes the fun part: in 2015, there was a conference in New York City and my generous publisher put me up at the Library Hotel. The Library Hotel is a delight to me because each room has a Dewey call number which dictates the decor. On this occasion, I was placed in Room 110.005--the Paranormal Room.

It was a turning point for Amber & Clay. I looked at the spooky photographs on the walls and thought, "My characters could meet if one of them were a ghost." And at that moment, the big structure of the novel came into my mind--the idea that the children were psychic counterparts as well as opposites. I ordered a copy of Sarah Iles Johnston's Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece and discovered that girls who died young were particularly apt to become ghosts. I learned that I could bind my two characters together with a curse tablet.

Can you tell us about the archeological "artifacts" you based many scenes on?

I went to a lot of museums when I worked on this book. I tend to think in terms of metaphors, so artifacts and objects inspire me. Museums not only give me ideas, but they trigger an acquisitive urge. I want to possess those artifacts, but they're locked behind glass. The God of Thieves told me I could steal them by putting them in my stories.

Were you an ancient Greece and Greek mythology scholar before writing the book or did you become an expert while writing it?

The original bibliography was actually 10 and a half pages long. My editor asked me to shorten it to three. I didn't know much when I began, so I read a lot of stuff--articles on Thracian tattoos and clay pits and looms and thrush in donkeys. Every time I turned around, there was something I didn't know: Did the Ancient Greeks have scissors? Buckets? Socks? (Yes, to all three.) When Melisto saw a butterfly on her way to Brauron, I spent over an hour researching Greek butterflies. I even tried to teach myself Greek. There's something spellbinding about the language.

You write in your author's note that writing in verse broke you out of a bleak stiffness you had been struggling with. Can you say a little more about what verse can do that prose can't?

I think of prose as a kind of elephant. It can be powerful, and it can be graceful, but it can't jump: one foot has to stay on the ground at all times. Prose has to make sense, to move logically and, because of that, the writer needs to make transitions. You can't leap from one thing to another without the reader experiencing it as abrupt. And sadly, transitions are the very devil to write. They're not the part of a book anybody notices, but they require meticulous craftsmanship.

Verse is like a flying squirrel. It leaps and soars and can easily telescope time and space. Verse is cinematic, flashing between close-ups and panoramas. The reader reads not only the words, but the white space around the lines. Line-lengths and spaces between stanzas send signals to the reader so the transitions can be visual, not crafted from words.

In verse, you can create momentum with rhythm, assonance; you can use vowels like violins and consonants as percussion. The white space around your words is always there to help you.

Of course, there's plenty of prose that's close to verse and verse can be prosaic. But though verse can also be the very devil to write, verse is... well, versatile. When I wrote about Rhaskos's lonely childhood in verse rather than prose, it moved more quickly and was imbued with energy. The intensity of his suffering increased, but some of the heaviness was mitigated.

Your details paint a vivid portrait of ancient Greece. Has world-building always been important to you in your writing?

Yes. It's part of the fun: living somewhere else at another time. It's part of what I love about historical fiction--seeing the world from an entirely different angle. I feel cheated when I read a book set in the past and it's really about 21st-century Americans dressed in farthingales.

What are you working on now?

I'm working on a dollhouse book for younger children. After all that Greek research, I wanted to write something miniature and less exacting in terms of research. Though I have had to try to learn a little bit about electrical wiring, so I could wire a tiny chandelier.... --Emilie Coulter

Past houseplant fiascos still haunt me, though, so I plan to conduct thorough research before taking a trip to my favorite garden shop. The perfect starting point is the reassuringly titled How Not to Kill a Houseplant: Survival Tips for the Horticulturally Challenged (DK, $14.99) by Veronica Peerless. Offering guidance on which plants suit different spaces, Peerless encourages readers to spend time nurturing and grooming their green companions and provides easy-to-follow advice on how to rescue sick plants.

Past houseplant fiascos still haunt me, though, so I plan to conduct thorough research before taking a trip to my favorite garden shop. The perfect starting point is the reassuringly titled How Not to Kill a Houseplant: Survival Tips for the Horticulturally Challenged (DK, $14.99) by Veronica Peerless. Offering guidance on which plants suit different spaces, Peerless encourages readers to spend time nurturing and grooming their green companions and provides easy-to-follow advice on how to rescue sick plants. Concerned about how to care for plants while away on vacation, I was thrilled to discover the homemade automatic watering devices created by Morgan Doane and Erin Harding, long-distance friends who share a passion for houseplants. In How to Raise a Plant: And Make it Love You Back (Laurence King, $16.99), Doane and Harding cheerfully explore all aspects of plant care and share fun DIY project ideas to inspire creative types. How to Raise a Plant is a labor of love, combining their formidable knowledge into one colorful guide.

Concerned about how to care for plants while away on vacation, I was thrilled to discover the homemade automatic watering devices created by Morgan Doane and Erin Harding, long-distance friends who share a passion for houseplants. In How to Raise a Plant: And Make it Love You Back (Laurence King, $16.99), Doane and Harding cheerfully explore all aspects of plant care and share fun DIY project ideas to inspire creative types. How to Raise a Plant is a labor of love, combining their formidable knowledge into one colorful guide. Plantopedia: The Definitive Guide to Houseplants (Smith Street, $40) by interior design nursery experts Lauren Camilleri and Sophia Kaplan is a detailed how-to guide dressed up as gorgeous coffee-table decor for houseplant aficionados. Its irresistibly lush photos offer some of the serene magic of indoor greenery while I mentally prepare for my new role as a plant parent. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Plantopedia: The Definitive Guide to Houseplants (Smith Street, $40) by interior design nursery experts Lauren Camilleri and Sophia Kaplan is a detailed how-to guide dressed up as gorgeous coffee-table decor for houseplant aficionados. Its irresistibly lush photos offer some of the serene magic of indoor greenery while I mentally prepare for my new role as a plant parent. --Shahina Piyarali, reviewer

Whether dwelling in fairy lands (

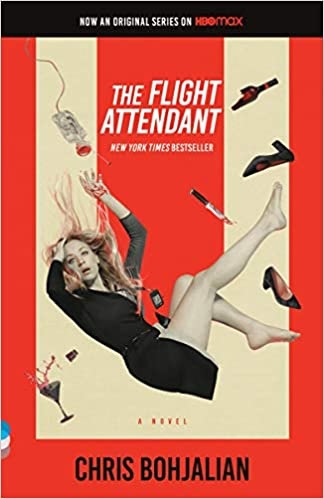

Whether dwelling in fairy lands ( The Flight Attendant, a series based on the novel by Chris Bohjalian, premiered on HBO Max November 26, 2020, and was renewed the next month following widespread acclaim. Kaley Cuoco stars alongside Michiel Huisman, Zosia Mamet and Rosie Perez as the titular freewheeling alcoholic whose layover in Bangkok ends in a dead body and questions from the FBI. The series was nominated for two Golden Globe Awards, among other accolades. In Bohjalian's original book, first published by Doubleday in 2018, the flight attendant's lethal layover is in Dubai instead of Bangkok. A paperback tie-in edition is available from Vintage ($16).

The Flight Attendant, a series based on the novel by Chris Bohjalian, premiered on HBO Max November 26, 2020, and was renewed the next month following widespread acclaim. Kaley Cuoco stars alongside Michiel Huisman, Zosia Mamet and Rosie Perez as the titular freewheeling alcoholic whose layover in Bangkok ends in a dead body and questions from the FBI. The series was nominated for two Golden Globe Awards, among other accolades. In Bohjalian's original book, first published by Doubleday in 2018, the flight attendant's lethal layover is in Dubai instead of Bangkok. A paperback tie-in edition is available from Vintage ($16).