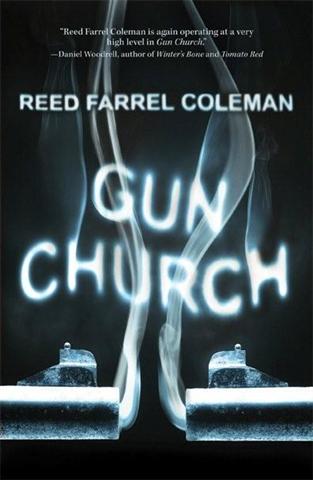

Called a hardboiled poet by NPR's Maureen Corrigan and the noir poet laureate in the Huffington Post, Reed Farrel Coleman is a former executive vice-president of the Mystery Writers of America. He has published 15 novels: two stand-alones and three series, including seven books in the Moe Prager series. His latest is Gun Church (Tyrus Books, $16.95), about a has-been writer, teaching in a mining town, who joins a quasi-religious, gun-toting group. Coleman resides on Long Island, N.Y.

Called a hardboiled poet by NPR's Maureen Corrigan and the noir poet laureate in the Huffington Post, Reed Farrel Coleman is a former executive vice-president of the Mystery Writers of America. He has published 15 novels: two stand-alones and three series, including seven books in the Moe Prager series. His latest is Gun Church (Tyrus Books, $16.95), about a has-been writer, teaching in a mining town, who joins a quasi-religious, gun-toting group. Coleman resides on Long Island, N.Y.

In Gun Church the guns are almost like characters in their own right. What kind of research did you do for this novel?

Oddly enough, I didn't do a lot of research into the guns themselves because I didn't want to have too much more knowledge of handguns than my protagonist, Kip Weiler. I will no doubt be receiving some angry fan mail about how I got this or that wrong. It's inevitable. I mean, I get angry e-mails about my usage of commas. I did do some research, but it was limited. I have, however, fired each of the weapons described in Gun Church. Always legally and under careful supervision. Research is an interesting subject for writers. Some of us love it. Me, I much prefer making stuff up. Otherwise I'd write nonfiction.

Gun Church is stand-alone, in contrast to most of your books, which are in series. Does your process differ when you write a stand-alone novel?

The process is different on its face. When I do an installment of the Moe Prager mystery series, for instance, I come to it knowing the protagonist, the regular cast of characters, the setting, the tone, the time frame, etc. It's like having a partially painted canvas already waiting for me on the easel. Of course, that's not all necessarily good. Writing isn't always about it being easy. Working within certain established confines means that I can't go off the rails to follow a story wherever it wants to go. Readers have valid expectations when they come to a series novel. So it's a bit of a trade off: ease for constraint.

A stand-alone is a blank canvas. It's a freer process, but a more difficult, more frightening one. Ah, but when it works, it's an amazing feeling.

The protagonist Kip Weiler discovers that his writing is more closely linked to real life than he could ever have dreamed. Is this a crime writer's worst nightmare?

I try to write fearlessly and for myself. That sounds selfish and inconsiderate of the readers, but it's quite the opposite. I want to put all my energy into the book itself and try not to consider any potential consequence beyond producing the finest book I can. Still, it's impossible to ignore works such as Stephen King's Misery. There's always a chance that the world you have created in a novel will cross that gray line between fiction and reality. When you think about it, authors are always tapping the resource of real life for inspiration and material. Doesn't it follow that there will be times when fiction will flip that around?

Do you have the ending in mind when you plot a mystery, or does the story evolve in the process?

Do you have the ending in mind when you plot a mystery, or does the story evolve in the process?

My author friends describe me as the ultimate pantser. (Pantser, as in doing it by the seat of one's pants.) I'm someone who detests outlining and plotting in advance. Each book is different for me. Sometimes I just sit down and start writing. At other times I have a vague idea of plot. Occasionally, I know the beginning or the ending. Gun Church was very rare in that the entire plot popped into my head all at once as a completely formed notion: beginning, middle, and end. Didn't help me write it any faster. Took five years!

You show many contrasts between New York City and the impoverished mining town of Brixton. Is the latter inspired by a real place?

I specifically didn't want any real spot on the map because I wanted to create a place that conformed to my imagination alone. I did keep places like West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky in mind. Coal mining is hard, dangerous work that produces great wealth and benefit for everyone but the miners. A tale like Gun Church needed to be set in a hardscrabble, unglamorous place. Brixton was that place.

This book features a friendship between two men whose fathers failed them in the worst possible ways. These fathers passed on their sins to the next generation. Meanwhile, Kip's sins follow him to the end of this book. Do you believe people can escape their past?

As desirable as escaping one's past may seem, I believe it's nearly impossible to do. It's akin to leaving town or running away with the circus: you bring the baggage of your past with you. In any case, your past is essential to who and what you are. This is not to say that you must always be a prisoner of your past. At some point, we must all take responsibility for ourselves. I believe we can indulge the past without surrendering to it.

And of course, lastly, what is your favorite gun?

Although the Colt Python is totally cool and even looks wicked sexy, the handgun I've enjoyed firing most was the classic .38 Smith & Wesson. --Ilana Teitelbaum, book reviewer at the Huffington Post

Reed Farrel Coleman: Writing Fearlessly

I picked up My Call to the Ring: A Memoir of a Girl Who Yearns to Box by Deirdre Gogarty with Darrelyn Saloom (Glasnevin Publishing, $20 paper) to read just a few pages. I finished it hours later, because this story of an Irish girl determined to become a pro boxer is absolutely captivating, even for someone (like me) who's not a fan of the sport. Tim Forbes left his corporate job for a dream job in sports; 10 years later, he was maxed out, so he traveled across North America to attend 100 games involving 50 different sports, hoping to rekindle his passion. In It's Game Time Somewhere (Bascom Hill, $15.95 paper), he does, with incisiveness and irreverence.

I picked up My Call to the Ring: A Memoir of a Girl Who Yearns to Box by Deirdre Gogarty with Darrelyn Saloom (Glasnevin Publishing, $20 paper) to read just a few pages. I finished it hours later, because this story of an Irish girl determined to become a pro boxer is absolutely captivating, even for someone (like me) who's not a fan of the sport. Tim Forbes left his corporate job for a dream job in sports; 10 years later, he was maxed out, so he traveled across North America to attend 100 games involving 50 different sports, hoping to rekindle his passion. In It's Game Time Somewhere (Bascom Hill, $15.95 paper), he does, with incisiveness and irreverence.

Called a hardboiled poet by NPR's Maureen Corrigan and the noir poet laureate in the Huffington Post,

Called a hardboiled poet by NPR's Maureen Corrigan and the noir poet laureate in the Huffington Post,  Do you have the ending in mind when you plot a mystery, or does the story evolve in the process?

Do you have the ending in mind when you plot a mystery, or does the story evolve in the process?