|

|

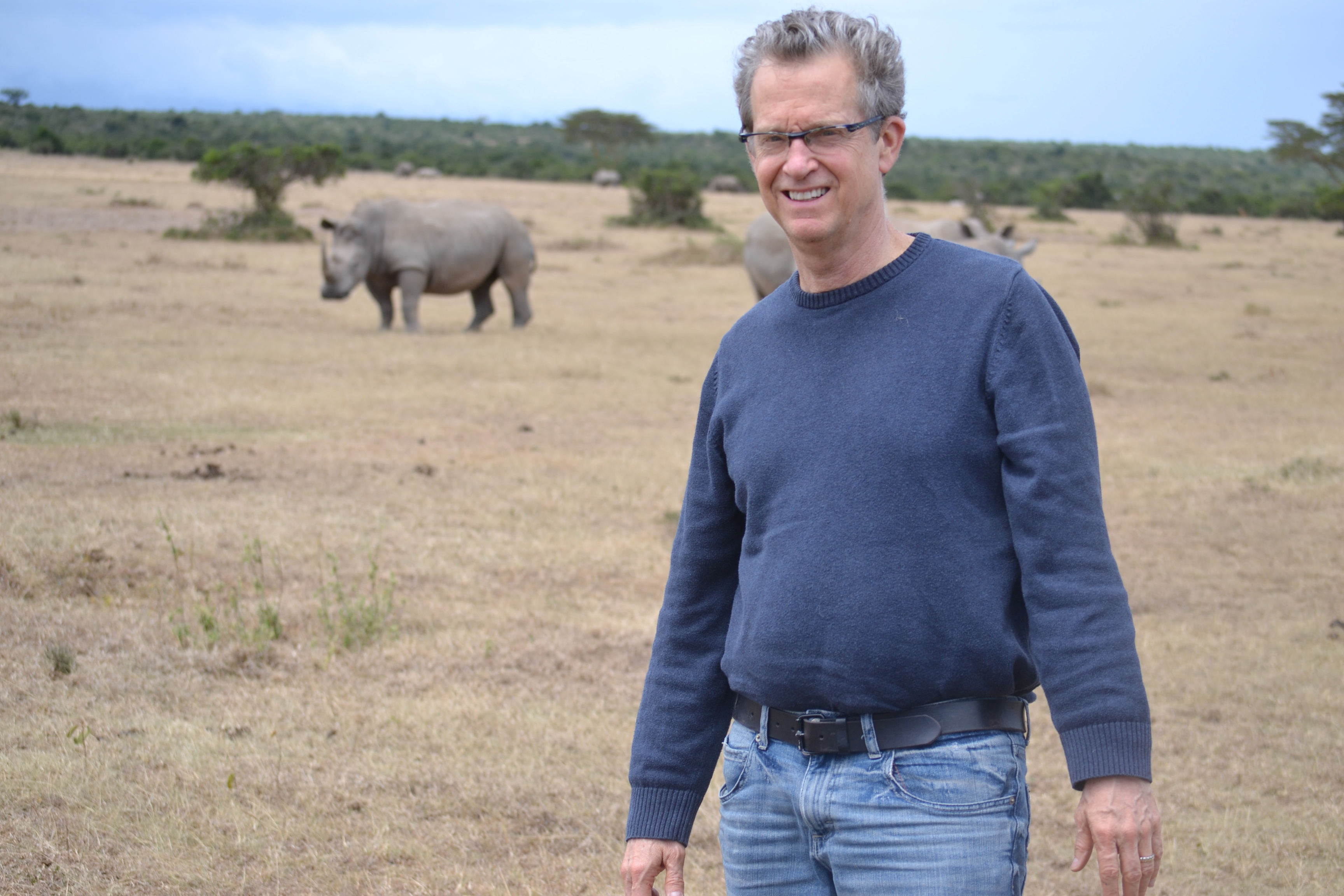

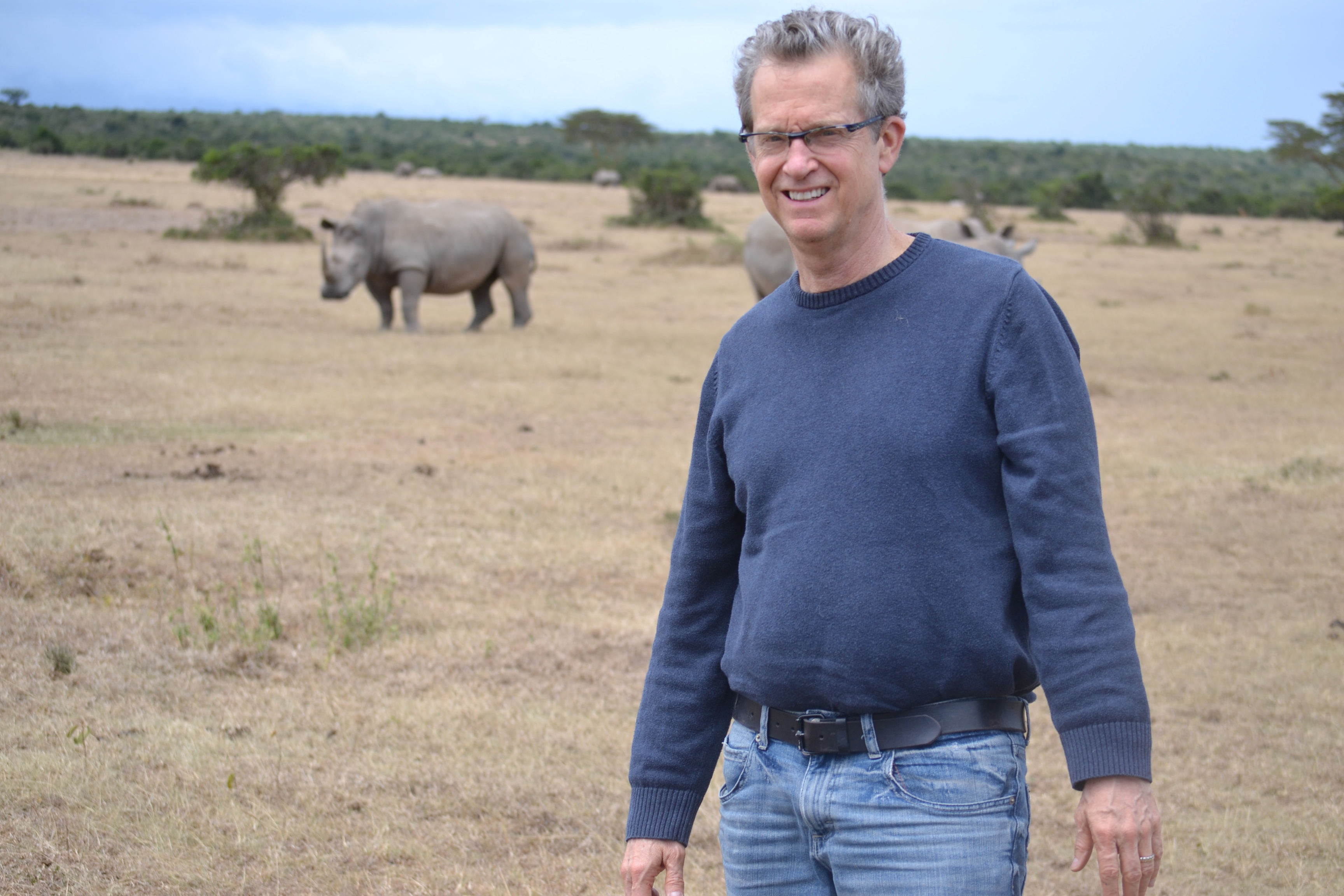

Pearson at Solio wildlife sanctuary: "Time and time again I was a matter of 15 yards from these rhinos."

|

Ridley Pearson is the author of more than two dozen novels, including The Red Room, Choke Point and The Risk Agent, plus the Walt Fleming and Lou Boldt crime series and many books for young readers. He lives with his wife and two daughters in St. Louis, Mo., and Hailey, Idaho. White Bone is the fourth novel in his Risk Agent series.

White Bone's plot centers on elephant poaching in Kenya. How did this issue come to your attention?

I heard a statistic about elephants, and it really shocked me. In 2014, the first real decent study documented that 100,000 African elephants had been killed in three years. One of every 12 African elephants had been killed by a poacher in 2011. Three-quarters of local elephant populations are declining. In nine years, there would be no more wild elephants in Africa.

Then I met Mikey and Tanya Carr-Hartley, who run a four-generation-old guiding service in Kenya. Eventually I went, under their care, to Kenya to do interviews and see the country and dig into the poaching, and my hair was blown back.

I interviewed 24 people over the course of three and a half weeks, and 23 of them in some way lied to me. These were very trustworthy sources, including our own (U.S.) State Department. Finally, my last interview was an activist lawyer, and we went through my interviews and she told me point by point who had fabricated what. My jaw dropped. There I'd been digging into this to help everyone, and in some way or another everyone had manipulated the truth.

|

|

"My guides Ole and Charcoal."

|

It was eye-opening, and dangerous. I was in Nairobi when there was a terrorist blast that killed 18 people. I was at a lodge when poachers killed a rhino 300 yards away from me while I slept. There's a scene in the book where Grace runs into these herdsman, and they try to rape her. Those were two guys I ran into when one of my guides had to go get a vehicle and I was left--by my own choice--and within 10 minutes I ran into these guys, and they did not like me. It was 20 or 30 minutes of, oh boy, all he has to do is lift that spear and I'm going down.

Is there a point at which research makes it harder to write fiction?

My approach is "faction." My charge is to suspend your disbelief, and I think it works best if I put more fact in than fiction. I do a lot of research. I learned about a guy who was investigating poaching and was a pilot over Mt. Kenya, and his plane happened to go down. A lot of people think that plane was sabotaged; it's never been proven. I told that story, where a guy was killed in the bush who had been investigating. I just made it a little more palpable and believable for the reader.

Were you searching for John Knox and Grace Chu's next case, or was this something you needed to write about first, and they were the best fit?

The latter. I just wondered if I could put Knox and Chu into Africa, and what that would look like.

|

|

"Ole showed me every plant that could kill you, every root that could heal you: it was unbelievable. I based all that information with Grace off my days with Ole."

|

I've written 51 books. And I haven't done this for probably 20 years, but I actually wrote the entire book and put it aside and started over. I just wasn't buying my own story. It wasn't lighting me up. And it wasn't the story my editor (Christine Pepe at Putnam, who's just one of the greatest editors who's ever lived) wanted. So I stepped back and thought: What am I doing wrong here? I've always wanted to do a book about a person out in the wild with nothing. I'm an Eagle Scout, so I've gone through some of this in my own teens. When Ole, my guide, told me that a white person wouldn't last 24 hours in the bush, I said, well, how could I last 24 hours in the bush? He showed me every plant that could kill you, every root that could heal you. It was unbelievable. I based all that information with Grace off my days with Ole.

How did you handle characterization?f

I felt a great depth of participation with Grace because of her circumstances. I think this is the book where readers of the series will go, "Oh, that's the Grace I've been waiting for." I learned a lot about her. She has a lot of stick-to-it-iveness that I really wasn't sure about. She's an accountant by trade, but she went through the Chinese army training, and had some short-lived intelligence experience. So I always sensed that she had this potential. This book was her chance to be out on her own, investigating something that's a little more money-oriented than pure fieldwork, and then it ends up Fieldwork with a capital F. In previous books you never really got in with Grace and felt her, and were afraid or proud or achieving with her.

The challenge is not to put everything in. In my fieldwork, there were some amazing moments. I had an encounter with one of the people who had lied to me. On the very last night I was there, he came up to me at a party and said, "Hey, listen. I'm terribly sorry about how I played that when we were at Solio." And I said "Yeah, so am I!" But at least he was man enough at the end to come up and say, "Sorry I just lied to your face." That was a very emotional moment for me. And you can't get them all in.

|

| "This is me in what they call a 'nice' town near Solio Lodge." |

You regularly write realistically about violence, depravity and corruption. Is this emotionally difficult?

I think you pay for it.

Every day for two years as I wrote this book, these images hung in my head. These stupid idiots come in with automatic weapons on ATVs, they massacre the elephants, they chainsaw their faces off for the tusks, and they're gone in 15 minutes. For all the dark that Grace and Knox went through, those are the images that haunted me. When you're there and you see these animals, just how majestic they are--it's absolutely despicable.

I want to route some of the money from the book there, and get some people at the end of the book to say, "I'll send $10 to them"--it doesn't have to be $100,000. It's just bizarre to me that this is going on, and none of our grandkids will see elephants except in a reserve or in a zoo. An elephant is being killed every 15 minutes, and has been since I started this and long before I started this.

That was the darkness I lived with. Everything else was manufactured. I've done a lot of research over 30 years. I've been inside the mind of a lot of devious criminals. I've spent time in prisons for the criminally insane. I've interviewed forensic psychiatrists who have themselves interviewed 140 mass murderers. I'll say, this is what my guy did, who is he? And we'll be eating dinner, and the stuff they describe stops me from eating. So there is darkness. And I pay for it. --Julia Jenkins, librarian and blogger at pagesofjulia

Ridley Pearson: The Price of Darkness

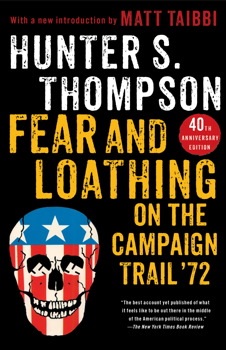

In December 1971, Hunter S. Thompson, armed with a first-generation fax machine he called the "mojo wire," began covering the 1972 presidential campaign for Rolling Stone. From his base in a rented apartment in Washington, D.C., an arrangement Thompson described as being like "living in an armed camp, a condition of constant fear," he spent the next year following every twist of what would be a tumultuous campaign. These collected dispatches became a book, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72, published by Straight Arrow Books in 1973.

In December 1971, Hunter S. Thompson, armed with a first-generation fax machine he called the "mojo wire," began covering the 1972 presidential campaign for Rolling Stone. From his base in a rented apartment in Washington, D.C., an arrangement Thompson described as being like "living in an armed camp, a condition of constant fear," he spent the next year following every twist of what would be a tumultuous campaign. These collected dispatches became a book, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72, published by Straight Arrow Books in 1973.