|

| photo: Franco Vogt |

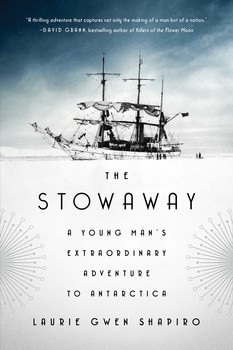

Laurie Gwen Shapiro is a fiction writer, award-winning documentary filmmaker and journalist whose writing has appeared in New York magazine, Slate, the Forward and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others. In The Stowaway: A Young Man's Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica (just published by Simon & Schuster), her first foray into book-length nonfiction, Shapiro recounts the true story of Billy Gawronski, a scrappy and determined teenager growing up in 1920s New York who sneaks onto a ship bound for the southernmost continent.

How did you discover Billy's story, and what made you decide to turn his story into a book?

I've always loved deeply reported nonfiction books that read like novels--some of my favorites are by David Grann and Susan Orlean. My New Year's resolution in 2013 was to find the right story for just such a book. Doing some research online, I saw mention of 500 children who'd paraded in the 1920s to City Hall to celebrate the return of a young man named Billy Gawronski, who'd stowed away to Antarctica. I started looking everywhere for this improbable kid, but it was only when I spelled his name a few different ways that a larger story racked into focus. (Newspapers had trouble with ethnic names back then.)

I knew I'd need a descendant to fill in the gaps in what the papers could tell me. You should have seen my sad, earnest Excel chart with over 100 names of possible relatives! I spent over a day calling Gawronskis up and down the Eastern seaboard to laughable results--so many hang-ups! Magic can happen though. Just when I was about to give up, I reached an elderly lady who had an Eastern European accent. I knew Billy Gawronski was American-born, so this couldn't be her kid. I was about to politely get off the phone, when I heard her say, "That was my husband!" I knew right then I had a book on my hands.

One of the most remarkable things about this book is how it captures the feel of a nation as the 1920s come to a close and the Great Depression begins. Who or what did you consult to get a sense of the times?

I researched the book for a year before I did a word of writing. I read dozens of books and hundreds of newspaper articles from the era, including harrowing stories of those plunged into poverty. My nonagenarian father became a trusted source, explaining to me what it was like for families to live off handouts--the shame and the hunger.

The most meaningful window to that time was a folder of desperate letters Billy wrote to Admiral Richard Byrd; he was eager for the expedition leader to help him get a job now that he'd returned to America. Unbeknownst to Billy, his mother was also writing pleading letters to Byrd. I found those tucked away in the Ohio State University's polar archives in Columbus, a treasure trove of American polar history. I spent several days there poring through correspondence and other amazing documents.

The scenes that moved me the most were those of Billy struggling to meet his immigrant parents' expectations. At what point did you realize that this adventure story was also a story of American immigration, and to an extent, generational differences?

The scenes that moved me the most were those of Billy struggling to meet his immigrant parents' expectations. At what point did you realize that this adventure story was also a story of American immigration, and to an extent, generational differences?

I was fortunate to make contact with Billy's widow early on, so I was privy to the challenges his family faced, and their dreams and expectations for him.

I also relied on old newspaper accounts from beat reporters of the Jazz Age who did a great job of turning Billy's parents into a part of the story. Readers wanted to check in with the rapscallion stowaway's folks from time to time. Billy started his journey as a truant who'd run away from what he figured would be a dreary life in his father's upholstery business. How was he shaping up at sea? Was his father proud of him now?

I also understood his roots. Billy grew up in the neighborhood where I was raised and still live, New York's Lower East Side, where dreams for so many new Americans began. All four of my grandparents lived on the Lower East Side after they arrived at Ellis Island, and my parents and their siblings grew up with similarly high parental expectations. My grandparents worked long hours so my parents could go to college. There was no time to find oneself or go off on an adventure.

It's amazing to read how Antarctica was a symbol of adventure and mystery in the 1920s, because in many ways, it still symbolizes those things. Why has the continent evoked such romantic feelings of adventure for so long?

Even 90 years after Byrd set up Little America, the first village on Antarctic ice, we're still learning about this mysterious land. On my own trip to Antarctica, I felt completely disconnected from civilization--for the first time in her life, this New York City girl could hear the sound of silence. And of course the nature is magnificent: the whales and the penguins and the gargantuan icebergs. I met people on my expedition who'd spent a lifetime reading and rereading classics like Apsley Cherry-Garrard's The Worst Journey in the World. That's what piqued Billy Gawronski's interest: all the adventure novels he'd been reading at his local library. They don't tell you how dangerous books can be! --Amy Brady, freelance writer and editor

Laurie Gwen Shapiro: An Antarctic Adventure

But sometimes a series persists. The recommendations turn up in the most unexpected places and provide compelling, heartfelt reasons to give it a whirl. So I take a deep breath and dig in.

But sometimes a series persists. The recommendations turn up in the most unexpected places and provide compelling, heartfelt reasons to give it a whirl. So I take a deep breath and dig in. As a result, I have started Tales of the City more than 40 years since its first serialization in the San Francisco Chronicle. After nine novels, Maupin ended his Bay Area adventure in 2014. With all that off his plate, he delivered his much-anticipated memoir, Logical Family, late last year.

As a result, I have started Tales of the City more than 40 years since its first serialization in the San Francisco Chronicle. After nine novels, Maupin ended his Bay Area adventure in 2014. With all that off his plate, he delivered his much-anticipated memoir, Logical Family, late last year.  In our review, Shelf Awareness said, "This beautifully written and evocative coming-out memoir is audaciously funny, reflective and wistful--and, like Maupin's novels, impossible to put down."

In our review, Shelf Awareness said, "This beautifully written and evocative coming-out memoir is audaciously funny, reflective and wistful--and, like Maupin's novels, impossible to put down."

The scenes that moved me the most were those of Billy struggling to meet his immigrant parents' expectations. At what point did you realize that this adventure story was also a story of American immigration, and to an extent, generational differences?

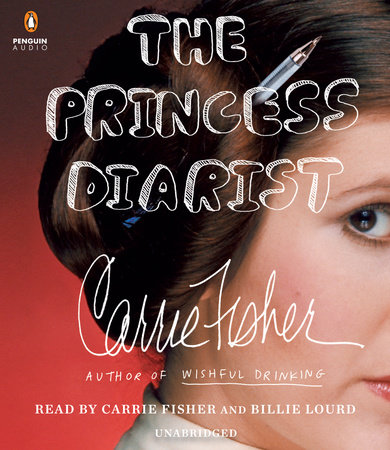

The scenes that moved me the most were those of Billy struggling to meet his immigrant parents' expectations. At what point did you realize that this adventure story was also a story of American immigration, and to an extent, generational differences? Carrie Fisher's death dims the many hopes of Star Wars fans eager to see her continued portrayal of Princess Leia in the Disney-revived franchise. Fisher's passing also marks the loss of a talented author, screenwriter and humorist, whose work includes candid depictions of her struggles with bipolar disorder and drug addiction. She died a week after suffering medical complications on a flight home from the European leg of her book tour for The Princess Diarist (Blue Rider Press), a memoir chronicling the making of the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope, including her affair with married co-star Harrison Ford.

Carrie Fisher's death dims the many hopes of Star Wars fans eager to see her continued portrayal of Princess Leia in the Disney-revived franchise. Fisher's passing also marks the loss of a talented author, screenwriter and humorist, whose work includes candid depictions of her struggles with bipolar disorder and drug addiction. She died a week after suffering medical complications on a flight home from the European leg of her book tour for The Princess Diarist (Blue Rider Press), a memoir chronicling the making of the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope, including her affair with married co-star Harrison Ford.