|

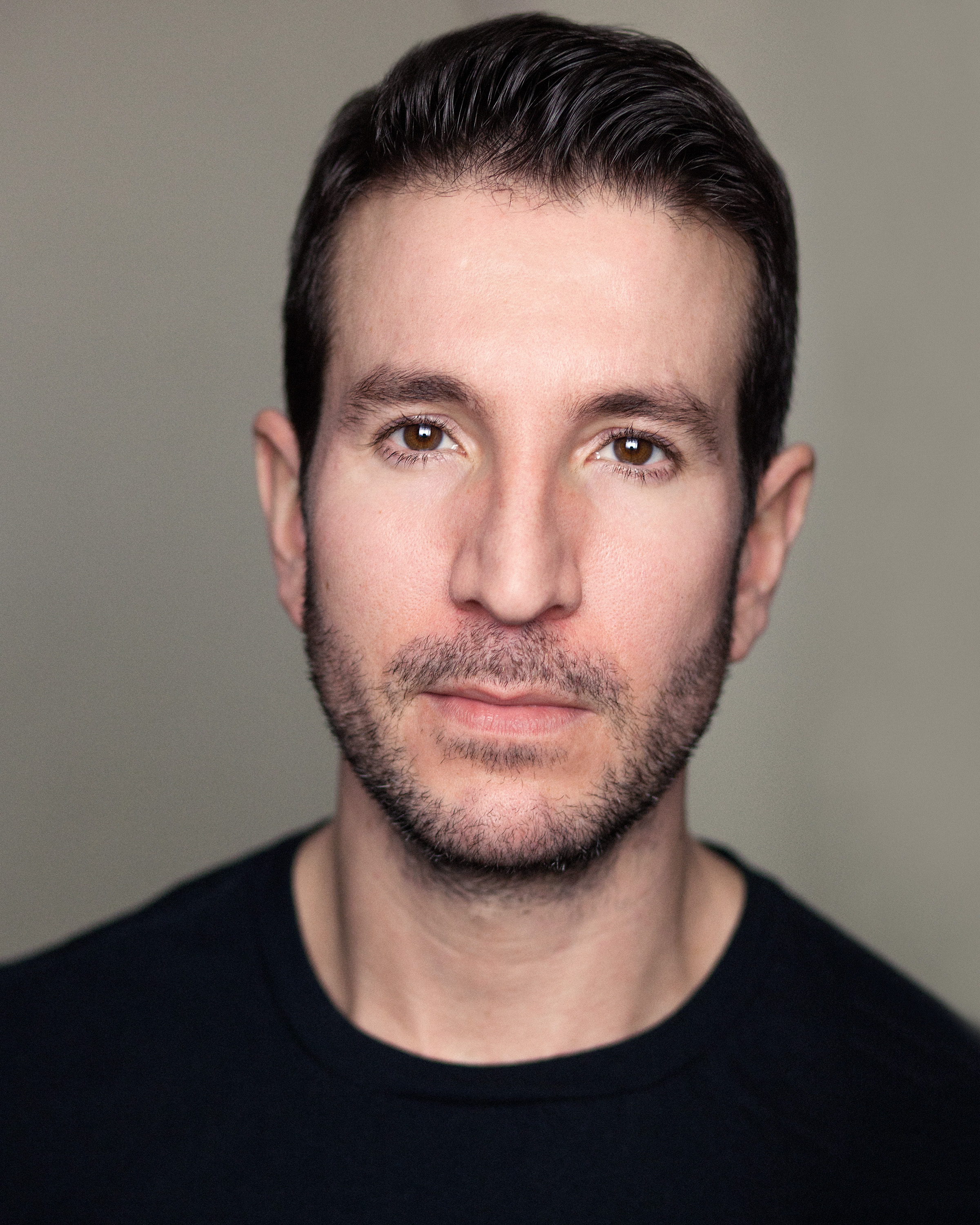

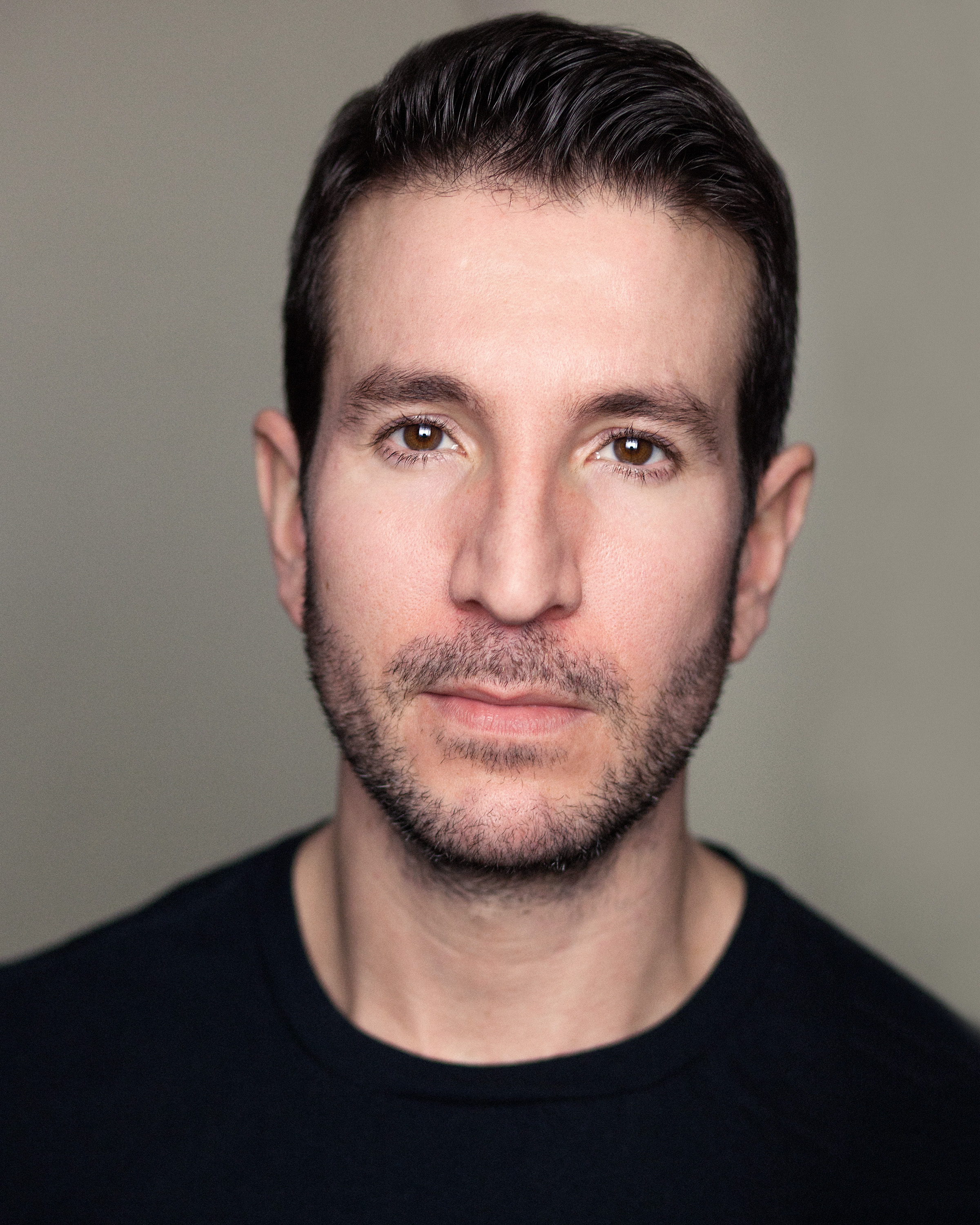

| photo: Wolf Marloh |

Alex Michaelides's youth, spent on Cyprus, was steeped in Greek mythology. He studied English literature and psychotherapy, worked in a secure psychiatric unit and became a screenwriter. He combined his experiences and knowledge to write the cinematic thriller The Silent Patient. It's the inaugural title from Macmillan's Celadon Books.

How does it feel to be the launch title for a new imprint with your debut novel?

It's really exciting. It's a lot to take in. My lifelong dream was just to have a book published, something I never really believed was possible. So to have Celadon choose The Silent Patient as the launch title is incredible.

What specifically about the myth of Alcestis captivates you?

The myth of Alcestis--her self-sacrifice, return from death and subsequent silence--has fascinated me since childhood. I'm not entirely sure why. It has something to do with her refusal to explain and the denial of conclusion, meaning the story doesn't really end but continues to play out in your imagination. Which is what happened to me. I experimented with the story in various incarnations--when I was a student, I tried updating it as a play, and then as a short film and then let it sit for another 15 years in my unconscious before I started wrestling with it again in The Silent Patient.

The actress Uma Thurman suggested Alicia be a painter. Did you have to study art to write the painting scenes convincingly?

I worked with Uma on a movie I co-wrote [The Con Is On], and I was writing The Silent Patient at the same time. I spoke to her about it on set and she gave me some great feedback. She's always looking for a way to elevate a pedestrian scene, seeking what she describes as the iconic image. Obviously, she knows a thing or two about being iconic.

Anyway, she suggested Alicia have a visually interesting profession, like being a painter. This struck a chord with me immediately, as the heroine of one my favorite novels, Cat's Eye, is a painter. [Margaret] Atwood's writing about the paintings and the interplay with Elaine's unconscious and memory is my favorite writing of hers. Interestingly, it was only when I made Alicia a painter that the character came alive in my mind. I used to paint a lot when I was younger and I've been around artists, so I just used my imagination.

You've said working in a secure psychiatric facility changed your life. How so? What surprised you most about the experience?

I was studying psychotherapy and started working at a secure unit for teenagers. It ended up becoming a big part of my life. It was an incredibly formative experience, in that it took me out of my head and got me relating to other people. That's a roundabout way of saying it helped me grow up and stop being so selfish. Some of the kids who were there had truly hard, unfair starts in life, but what amazed me was how they would always respond if given the right kind of care in the right kind of environment. I didn't know I was going to write the novel when I worked there, but years later when I thought about a good setting for the kind of story I wanted to write, I thought of a secure unit. It's an entirely made-up place in The Silent Patient, but the inspiration was there.

Part of your novel is about looking at situations from different angles to see something unexpected. While writing it, did anything--related to process or plot--reveal itself as being different from your preconceived ideas?

To be honest, the answer is no. I feel--and I could well be wrong--that for this kind of novel, which is essentially a detective story, the architecture is paramount. The really hard work is the planning and re-planning of the story, so some of the authorial conjuring tricks you want to pull off are so carefully planned that it leaves little room for improvisation or surprises for me as a writer. Where I did allow myself free rein was the dialogue, and watching the characters come alive and talk to each other without me dictating it was a fun and surprising experience.

You're also a screenwriter. What made you decide this story had to be in novel form?

I felt I had a book in me. I had always wanted to be a novelist as a child and wrote a novel and a half before I was 18. I got discouraged, I think, and was also attracted by my love of movies. But to be honest, writing The Silent Patient alone in a cafe or in my apartment was the happiest I've felt as a writer. Just working on a sentence, moving words around, finding the right word--all that makes me very happy. I've really enjoyed going into people's heads in a way you can't in film, or at least not in the same way.

The novel has already been optioned for film. How involved will you be with the screen adaptation? What are your expectations or hopes for it?

I have been hired to write the script, which should be a fascinating experience. I have no problem with taking the whole thing apart and then putting it back together again for a different medium. It's certainly going to have its challenges and will probably be a very different animal from the book. It will be a good lesson in letting go! --Elyse Dinh-McCrillis

Salt by Hannah Moskowitz (Chronicle, $17.99, ages 12-up)

Salt by Hannah Moskowitz (Chronicle, $17.99, ages 12-up) Got to Get to Bear's by Brian Lies (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $17.99, ages 4-7)

Got to Get to Bear's by Brian Lies (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $17.99, ages 4-7) Imagine! by Raúl Colón (Paula Wiseman/S&S, $17.99, ages 4-8)

Imagine! by Raúl Colón (Paula Wiseman/S&S, $17.99, ages 4-8) Africville by Shauntay Grant, illus. by Eva Campbell (Groundwood Books, $18.95, ages 4-7)

Africville by Shauntay Grant, illus. by Eva Campbell (Groundwood Books, $18.95, ages 4-7)