|

| photo: Adam Shemper |

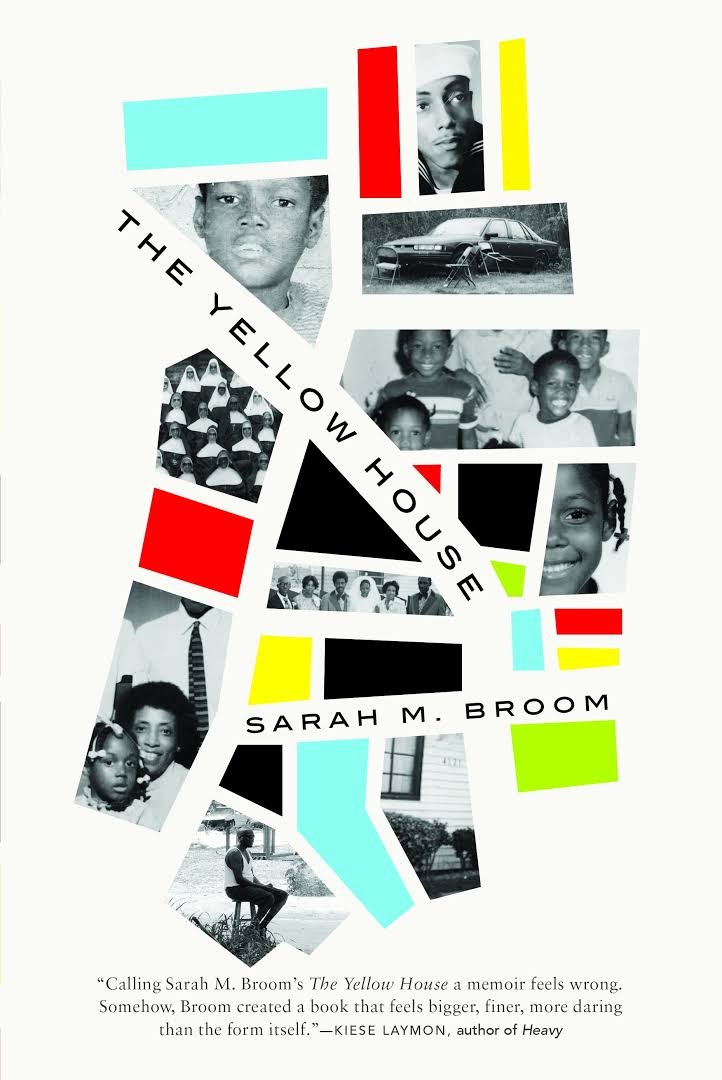

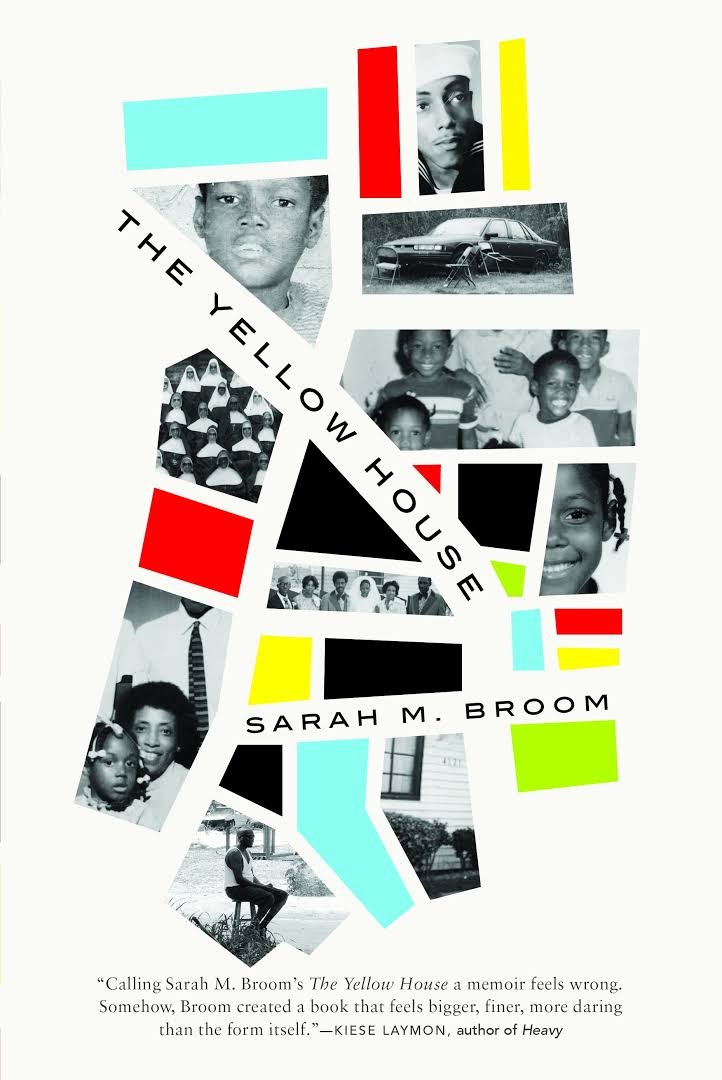

Sarah M. Broom's debut memoir, The Yellow House (Grove Press, $26), is a deeply personal portrait of a family, a house and a city still coming to terms with the destruction from Hurricane Katrina--and with destructive forces entirely manmade, including institutionalized racism and the frequent mythologizing of New Orleans. A native of New Orleans East, Broom holds a Masters in Journalism. She has been awarded a Whiting Foundation Creative Nonfiction Grant as well as fellowships at Djerassi Resident Artists Program and the MacDowell Colony.

Your urge to record what's around you has been lifelong; by fourth grade your nickname was "Tape Recorder" for your ability to parrot nearby adults' conversations. Did journalism and memoir feel inevitable?

No, but storytelling certainly did! I wrote my first book when I was very young--maybe six. It was 10 pages, broken into six sections. The edges were stapled and there was an author's bio on the back. My mother, Ivory Mae, had it stored away with her important papers. She gave it back to me when I was reporting this book. That is a meaningful circle for me.

Sometimes you build images gradually, while other times you slip in a line that so perfectly captures something, nothing else needs to be said. Did you find yourself writing more poetically about certain subjects or fighting that tendency anywhere?

When I'm writing, I'm thinking about time, pace, rhythm, cadence. Sometimes the language is upright, more formal in sound--my getting out of the story's way. Other times, the words lay down, lean, fall on each other, play differently, which makes a different sound and music. That's the part of craft that I love most. Thinking about how to stack the language.

You write, "Sometimes, when I want the world to go blurry again, I remove my glasses.... In this way, I learn to see and to go blind at will." What kind of armor does it take to gather such a personal story, including seeking answers to questions that some in the family might prefer to remain blurry?

The armor is the work--the utter difficulty of writing. Finding structure and shape. This book is layered with family lore, archival research, hundreds of hours of interviews with family members. This may sound strange, but that work felt less personal to me--especially in the early drafts--than like a Sisyphean task of making something of the evidence and the silences, which sometimes speak loudest.

I spent many hours of every day revving up to do the work. I had to give myself permission--over and over again--to transgress; the baby writing the history of a black American family; writing about my experience in city politics; telling on New Orleans, the mythologized, beloved city. Permission. I was also quite obsessed, burying myself in the research, in library archives, in the questions. I drove up and down Louisiana roads, to Raceland, where my father was born, and elsewhere. That ritual and practice protects me in many ways still.

Your mom's line "You know this house is not all that comfortable for other people" haunts this book, and you acknowledge the discomfort of putting your family's stories out there. What are the upsides of discomfort?

Your mom's line "You know this house is not all that comfortable for other people" haunts this book, and you acknowledge the discomfort of putting your family's stories out there. What are the upsides of discomfort?

I've never made or done anything I've felt even vaguely confident about without an enormous amount of discomfort, which appears as agitation when it comes to me. Here's the wonderful thing: when faced, most things become less daunting. Not immediately, perhaps. The American problem, as I see it, is partly a terror of any discomfort. We are masters of looking away--oh, that film/book/artwork is "hard to watch." And so we don't face; we conjure fantasy, rely on our myths, get overtaken by amnesia. As a black woman writer, I don't have this privilege. I need to know for my own safety and security, as did my mother.

Four "movements" compose The Yellow House. That word is so rich in connotations: motion, music, social advancement. Why did you choose to structure the book this way?

Early in the process, I laid out the rooms of The Yellow House in a line on the floor, just as our shotgun house was structured. Living room, Mom and Dad's room, kitchen, etc. That led me to consider the ways in which the book was a house and needed a kind of architecture, flow. What room would the reader enter first, I wondered. Where would they sit and pause, how comfortable would that seat be, what would they see, how much would that first room tell them about the rest of the house? My main question was to see if it was possible to resurrect a house with words. The movements became my architecture, a way of speaking on multiple frequencies to create layer and also mystery. They allowed me to, in a way, write a few different yet interconnected books, with varying feeling and tone. The book is quite literally about a series of physical movements--dislocation, departures and returns, settling in. Like a symphony, they can be read in parts but they are stronger and make the most sense when taken together, in context, like a long Fela Kuti or Sun Ra track.

You're a sponge for language. You write an unforgettable original line, adapting your Sunday school vocabulary to your burgeoning sense of good choices: instead of just saying no to drugs, you offer: "Just rebuke those drugs!" Where do you find yourself soaking in new language these days?

Oooh. From everywhere. I most love hearing how people talk. I live in Harlem; much of what is recorded in my notebook are things people have said to me on the street. Harlem people remind me of New Orleans people--some of the best talkers. I love to overhear, focusing on how words are put together to make you feel--not merely hear--the sentiment. Often, while listening, I'll think about June Jordan saying, "don't you idolize the diction of the powerful," and think about the person speaking: they've won! I also have a habit of writing down what people are saying during phone calls, especially ones with my mother. I write down almost everything she ever says. Also, I live in a house where (the language of) music is always playing, with a filmmaker who adores reading and words as I do. I do love to abide in and with language, especially someone else's. And to note its limitations, its frames, so to speak. The best poets master the writing of a line in order to break it. I learn from them. --Katie Weed, freelance writer and reviewer

Sarah M. Broom: Resurrecting a House with Words

Myla Goldberg's novel Feast Your Eyes (Scribner, $28) is written as a retrospective exhibition catalogue of photographs by the late Lillian Preston. Composed by her estranged daughter using letters, journal entries and interviews, the catalogue takes a biographic shape. Besides a scandalous obscenity trial over a nearly nude picture of her young daughter, Preston's legacy is her skill in capturing the profundity of quotidian scenes. The undershirts billowing on clotheslines webbed across apartment ventilation shafts or a child's arrested leap from a rope swing slung from an abandoned building are reminiscent of Vivian Maier or Helen Levitt's famous street photographs, and the paramnesia I suffered trying to look up Preston's work online I attribute to Goldberg's skillful descriptions.

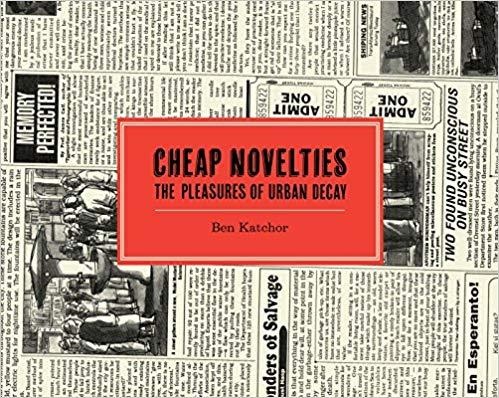

Myla Goldberg's novel Feast Your Eyes (Scribner, $28) is written as a retrospective exhibition catalogue of photographs by the late Lillian Preston. Composed by her estranged daughter using letters, journal entries and interviews, the catalogue takes a biographic shape. Besides a scandalous obscenity trial over a nearly nude picture of her young daughter, Preston's legacy is her skill in capturing the profundity of quotidian scenes. The undershirts billowing on clotheslines webbed across apartment ventilation shafts or a child's arrested leap from a rope swing slung from an abandoned building are reminiscent of Vivian Maier or Helen Levitt's famous street photographs, and the paramnesia I suffered trying to look up Preston's work online I attribute to Goldberg's skillful descriptions.  Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer, the illustrated narrator of Ben Katchor's collection Cheap Novelties (Drawn & Quarterly, $22.95), likewise makes the fictional unnamed urban neighborhood he perambulates feel like a remembered place through his attention to ordinary details. In the series of comic panels, Knipl tallies phone booths, vanished newsstands and movie theater marquees. He observes obscure trades like electric sign watchers and records the magical banalities of discarded beauty school cases or dropped playing cards.

Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer, the illustrated narrator of Ben Katchor's collection Cheap Novelties (Drawn & Quarterly, $22.95), likewise makes the fictional unnamed urban neighborhood he perambulates feel like a remembered place through his attention to ordinary details. In the series of comic panels, Knipl tallies phone booths, vanished newsstands and movie theater marquees. He observes obscure trades like electric sign watchers and records the magical banalities of discarded beauty school cases or dropped playing cards. It's this same attention to familiar urban detritus that Susanna Ryan uses in Seattle Walk Report (Sasquatch Books, $19.95) to inspire readers to get out and explore their own neighborhoods. Triggered by the popularity of her formerly anonymous Instagram feed of the same name, Ryan's collection of illustrated field notes maps exploratory walks through her hometown. Dutifully recording paper cup sightings alongside historic building entrances, Ryan emphasizes the pleasures of small discoveries that might go otherwise unnoticed. Even if your own neighborhood explorations don't include counting lost socks or tracing the taxonomy of fire hydrants and water fountains, Ryan hopes you'll at revel in the little joys and mysteries of your sidewalk discoveries.

It's this same attention to familiar urban detritus that Susanna Ryan uses in Seattle Walk Report (Sasquatch Books, $19.95) to inspire readers to get out and explore their own neighborhoods. Triggered by the popularity of her formerly anonymous Instagram feed of the same name, Ryan's collection of illustrated field notes maps exploratory walks through her hometown. Dutifully recording paper cup sightings alongside historic building entrances, Ryan emphasizes the pleasures of small discoveries that might go otherwise unnoticed. Even if your own neighborhood explorations don't include counting lost socks or tracing the taxonomy of fire hydrants and water fountains, Ryan hopes you'll at revel in the little joys and mysteries of your sidewalk discoveries.

Your mom's line "You know this house is not all that comfortable for other people" haunts this book, and you acknowledge the discomfort of putting your family's stories out there. What are the upsides of discomfort?

Your mom's line "You know this house is not all that comfortable for other people" haunts this book, and you acknowledge the discomfort of putting your family's stories out there. What are the upsides of discomfort?  Lee Bennett Hopkins, American educator, children's poet and advocate of poetry in education, died on August 8 at age 81. Born in Scranton, Pa., and raised in a housing project in Newark, N.J., Hopkins earned a Masters in education and taught elementary school. Between 1968 and 1976, he was a curriculum specialist for what was then Scholastic Magazines, where he began writing books for teachers, publishing articles in Horn Book and Language Arts, and anthologizing children's poetry. In 1976, Hopkins left Scholastic to pursue writing and education advocacy full-time. Pass the Poetry, Please (1972, revised in 1987 and 1998) outlined his thesis: that poetry could complement any children's curriculum and it is important to match students with the right poet. To that end, Hopkins collected more than 100 anthologies of kid's poetry over the course of his life. He is recognized by Guinness World Records as the "world's most prolific anthologist of poetry for children."

Lee Bennett Hopkins, American educator, children's poet and advocate of poetry in education, died on August 8 at age 81. Born in Scranton, Pa., and raised in a housing project in Newark, N.J., Hopkins earned a Masters in education and taught elementary school. Between 1968 and 1976, he was a curriculum specialist for what was then Scholastic Magazines, where he began writing books for teachers, publishing articles in Horn Book and Language Arts, and anthologizing children's poetry. In 1976, Hopkins left Scholastic to pursue writing and education advocacy full-time. Pass the Poetry, Please (1972, revised in 1987 and 1998) outlined his thesis: that poetry could complement any children's curriculum and it is important to match students with the right poet. To that end, Hopkins collected more than 100 anthologies of kid's poetry over the course of his life. He is recognized by Guinness World Records as the "world's most prolific anthologist of poetry for children."