_Jeremy_Handrup.jpg) |

| (photo: Jeremy Handrup) |

Gabriel Bump's fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Slam magazine, the Huffington Post and elsewhere. He received his MFA in fiction from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, and now lives in Buffalo, N.Y. His debut novel, Everywhere You Don't Belong (Algonquin), is set on the South Side of Chicago, where Bump grew up. The novel's protagonist is Claude, who was abandoned by his parents as a child and lives with his grandmother. Claude must choose between his desire to escape Chicago and his love for the people he would leave behind.

Let's talk about your approach to dialogue. Characters often speak in short bursts and there's a pretty rapid back-and-forth during some conversations. It reminded me of a play.

In college, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I took a few playwriting workshops taught by Jenny Magnus. There, I learned that dialogue can and should have its own style. In grad school, at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, as I started writing this book in earnest, I read everything by August Wilson and Suzan-Lori Parks. When dialogue works best, like in Wilson's and Parks's work, the aim is frugal economy.

I try to accomplish several things in one line. I want to move the plot forward, give a sense of character, transmit emotion--to name a few goals, which change given the context. Those short bursts also allow me to build a rhythm. There are a few long monologues in the book. For example, Connie Stove only speaks in long monologues. After all those short bursts, I hope the long monologues provide a fun break in the rhythm.

The community you write about has a strong sense of history--in one scene, the memory of Fred Hampton's killing seems to loom as large as more recent tragedies. How do you think that long memory filters down to younger generations like Claude's? How does it change the way they look at the world?

I grew up two blocks north of Emmet Till Road, a section of 71st Street named after the lynched young man. In high school, when I first started reading about the Black Panther Party and the civil rights movement, I learned about Fred Hampton and his unjust killing. In places like the South Side of Chicago, I believe, curious young people feel a desire to understand their surroundings. For example: Why is my neighborhood 95% black and my friend's neighborhood is 95% white? America's history provides answers. For me, that long memory was encountered through journalism. I worked on my high school newspaper. I enjoyed writing stories about segregation, gun violence, and civil rights. Young people access that long memory in different ways. Claude, for example, discovers it through Paul and Grandma.

I can't speak for everyone in my generation. I can say that learning about America's long and complicated racial history has made me realize that ills in minority communities aren't random or the result of innate inferiority. These are ills that are deliberate and conceived by outside forces. Understanding that truth gives me some hope that these ills can change with serious systematic reforms.

Claude's desire to leave the South Side seems to be replaced by homesickness once he actually gets out. Did you experience anything like that after leaving your hometown?

Claude and I left Chicago for different reasons. I didn't leave because I was disillusioned. I left because I wanted to study journalism at the University of Missouri. I loved Chicago, still love Chicago. When I left, however, I felt the same homesickness. I felt like I didn't belong in Missouri. I dropped out and moved back to Chicago after sophomore year. When I left for grad school, three years after moving back, I felt that same sensation of not belonging in Massachusetts. It's difficult to articulate. Back home, in my neighborhood, I was used to seeing people like me every day. Away from Chicago, the world was different. This book started by trying to define what "belonging" somewhere meant.

Obama is referred to a few times in the book. It makes sense given the setting, but I wondered if there was a disconnect between the kind of hope he offered and the seemingly unchanging or worsening circumstances in the South Side that you wanted to highlight.

The South Side of Chicago, I believe, felt a more acute hope than the rest of the world when Obama was running for president. We claimed him as our own. He claimed us as his own. First Lady Michelle Obama spent her childhood years on Euclid Avenue, a few blocks south of where I grew up. Once Obama got elected, the reality of his job set in. Of course, he wasn't just our president. That was never a real possibility. I was in Grant Park when he gave his acceptance speech. I rode the bus home feeling the world had changed for the better. Then, soon after, reality sunk in. Having Obama in the White House was never going to change the systematic and long-running diseases afflicting Chicago. Chicago had to cure itself.

Basketball and the Chicago Bulls are hugely important to your characters, in a way that might be hard for outsiders to understand. Is there something going on here beyond the usual sports fandom?

Basketball in Chicago is similar to football in Texas. Even before the Jordan years, basketball was huge. There's this amazing mix of high-level local talent and fan obsession. I spent a few years working as a high school basketball scout. I still haven't experienced a sporting event similar to a Chicago Public League basketball game. I imagine there are European and South American soccer matches with similar atmospheres.

The whole world was obsessed with Michael Jordan and the Bulls. Imagine if that was your city, your team, your hero.

How much of your own life and experiences did you feel comfortable putting in the book?

Claude and I experienced different lives. The settings are similar. He grew up on Euclid Avenue. I grew up on Euclid Avenue. He went to school in Missouri. I went to school in Missouri. That's about where the comparisons end. As best I could, I did, however, try to put my emotions into Claude. How I felt when I first fell in love, for example. How homesickness felt. Anger. Sadness. Loneliness. In an emotional sense, I'm all over this book.

After he goes to college, how does it isolate Claude to be around people like his roommate Kenneth, who belong "in a world without time and emergencies"?

That's an isolation felt by many first-year college students from urban environments. You spend your whole life in a city, with all its problems and beauty, and--wham--you're in the middle of nowhere. Now, I do think if Claude spent more time getting to know Kenneth and people like him, he'd realize, like I have, that every place operates on its own time, has its own emergencies.

You write that "anger has to go away when you go to work or go to school or ride the bus or go to the grocery store or go to a movie downtown." In your own life, if you experience such anger, how do you cope with it?

For me, writing and reading are the only effective salves. Not just with anger. This book grew out of anger and loneliness, yes--some confusion, some angst. When I'm feeling any strong emotion, writing and reading helps clarify it, calms me down.

That riot scene, which you've quoted, sprang from the anger I felt watching the Ferguson riots on TV from my couch in Massachusetts. I was shaking with anger. Writing through that anger helped calm me down, helped clarify. Writing didn't, however, make the anger disappear. It doesn't help me to walk around shaking with anger at the world. Still, look at the world. Sometimes, I don't know what else to do. --Hank Stephenson

Disciplined readers will delight in New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul's My Life with Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues (Holt, $27), a memoir Paul has constructed around the reading record she's maintained since 1988. (My own version of "BOB"--Book of Books--dates to late 1979.) Paul's heartfelt book is less a detailed account of her reading than it is the story of books as her life companions, whether she was trekking solo across China or mourning the end of her brief first marriage.

Disciplined readers will delight in New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul's My Life with Bob: Flawed Heroine Keeps Book of Books, Plot Ensues (Holt, $27), a memoir Paul has constructed around the reading record she's maintained since 1988. (My own version of "BOB"--Book of Books--dates to late 1979.) Paul's heartfelt book is less a detailed account of her reading than it is the story of books as her life companions, whether she was trekking solo across China or mourning the end of her brief first marriage. Do you fall into despair when you see a headline pronouncing the "end of reading?" Leah Price's What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: The History and Future of Reading (Basic Books, $28) could be the antidote. In this slim volume, Price, a Rutgers University English professor and book historian, argues persuasively that the consumption of the written word has always adjusted to new technologies, and that the shortened attention spans that electronic reading triggers are only the latest surmountable challenge.

Do you fall into despair when you see a headline pronouncing the "end of reading?" Leah Price's What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: The History and Future of Reading (Basic Books, $28) could be the antidote. In this slim volume, Price, a Rutgers University English professor and book historian, argues persuasively that the consumption of the written word has always adjusted to new technologies, and that the shortened attention spans that electronic reading triggers are only the latest surmountable challenge. And for those inclined to pass judgment when scanning the bookshelves of a new acquaintance, My Ideal Bookshelf (Little, Brown, $24.99) is a treat for the mind and eye. This small coffee-table book, a collaboration between editor Thessaly La Force and artist Jane Mount, features La Force's interviews with more than 100 writers and other creatives, among them Rosanne Cash and George Saunders, who each select books that possess special meaning for them. Mount reproduces the spines of those books in colorful illustrations.

And for those inclined to pass judgment when scanning the bookshelves of a new acquaintance, My Ideal Bookshelf (Little, Brown, $24.99) is a treat for the mind and eye. This small coffee-table book, a collaboration between editor Thessaly La Force and artist Jane Mount, features La Force's interviews with more than 100 writers and other creatives, among them Rosanne Cash and George Saunders, who each select books that possess special meaning for them. Mount reproduces the spines of those books in colorful illustrations.

_Jeremy_Handrup.jpg)

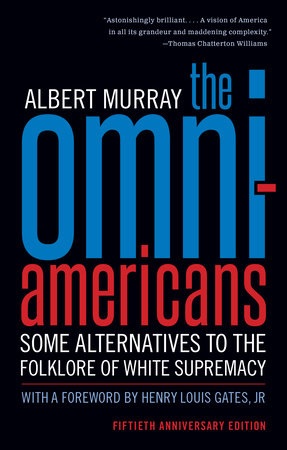

African American novelist, essayist, biographer and jazz critic Albert Murray (1916-2013) was born in Mobile, Ala., graduated from and later taught at the Tuskegee Institute. In 1943, he joined the U.S. Army Air Forces, hoping to "live long enough for Thomas Mann to finish the last volume of Joseph and His Brothers." After the war, he earned a masters in English from New York University, where he befriended Ralph Ellison and Duke Ellington. Murray retired from the Air Force as a major in 1962 and settled in Harlem. He published his first book, The Omni-Americans, in 1970 and held professorships across the country, including at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Colgate University, Emory University, Drew University and Barnard College. Murray's music writing influenced jazz legend Wynton Marsalis. They founded Jazz at Lincoln Center together in 1987.

African American novelist, essayist, biographer and jazz critic Albert Murray (1916-2013) was born in Mobile, Ala., graduated from and later taught at the Tuskegee Institute. In 1943, he joined the U.S. Army Air Forces, hoping to "live long enough for Thomas Mann to finish the last volume of Joseph and His Brothers." After the war, he earned a masters in English from New York University, where he befriended Ralph Ellison and Duke Ellington. Murray retired from the Air Force as a major in 1962 and settled in Harlem. He published his first book, The Omni-Americans, in 1970 and held professorships across the country, including at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Colgate University, Emory University, Drew University and Barnard College. Murray's music writing influenced jazz legend Wynton Marsalis. They founded Jazz at Lincoln Center together in 1987.